By

Bede Dwyer

Introduction.

This is written to give a historical context to

the information that Stephen Selby brought back from the museum in Urumqi on

some ancient bows. They have not been widely published in Chinese or English,

but they are very significant for the study of archery history.

Stephen supplied me with the descriptions, but my imagination supplied

the reconstructions. I also redrew his sketches so any errors are mine.

The

Location

Shanshan County, to the east of Urumqi, is on

the Northern Route of the Silk Road, which splits in two to pass the extremely

arid Takla Makan Desert. To the East is the Gobi Desert; to the west is the

Tarim Basin, which drains the mountains to the north. Its watercourses

eventually evaporate in the Takla Makan. Subeshi (Subeixi) is situated to the

east of the famous Silk Road town of Turpan (Turfan). Since early exploitation

by foreign archaeologists in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, the

area has continued to reveal amazing relicts of the past. Modern Chinese

archaeologists have revealed more details of the ancient inhabitants and their

ways of life. The unique dry conditions have preserved usually perishable artifacts

and even the bodies of some of the people buried there.

What have surprised many in the West were the

European features of some of the bodies. However, ancient Chinese historians had

recorded the variety of races on their northwestern border as far back as the

Han Dynasty. This area was both a trade route and the point of contact many

people from different environments and cultures. People farmed and traded in the

oases and nomads visited both for trade and warfare.

The Artifacts

Stephen Selby examined several bows in Urumqi

that were of various designs and from several periods. One type of great

significance to the history of archery was very similar to bows familiar in the

West from Greek, Persian and Scythian [i]

art. I will discuss why this is not so surprising below, but firstly I will

describe one of the bows.

The bow in question possessed a feature that is

no longer common in modern composite bows. It was thick and narrow in the

cross-section of that part of the limb where it bends. Unlike later bows, with

their broad lenticular or rectangular bending sections, this bow had a

triangular section with the apex on the belly side of the limb. The back of the

bow was slightly convex and formed the base of the triangle. At the centre of

the bow, the limbs are 4 cm wide. For a greater part of the limb it had this

unusual shape.

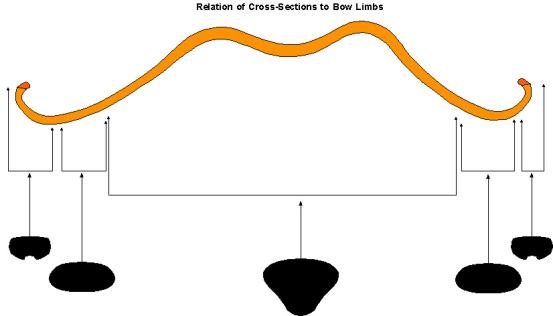

Figure 1

Cross-section of centre area of bow.

Another feature that was rare in more recent

traditional composite bows was that the tips were smoothly recurved. The

recurves had string grooves on their belly sides like modern target recurve

bows. The cross-section of the recurve was more like a slightly flattened oval.

For part of this there is a groove on one side as just mentioned. This feature

is totally unlike the bow tips on later composite bows. The term we use for bow

tips, “siyah”, is not really appropriate [ii].

Figure 2

Cross-section of recurve.

In outline, the bow looks like the Classical

Cupid’s bow of Greek and Roman art. This is not an accident. Despite being

found in the modern confines of China, this bow represents a survival of the

ancient Scythian bow, which was used from Italy in the west to the north of

China in the east. Roman armies might have carried them even further west.

Remains of later Roman archery equipment have been found in Britain, both grip

scales and laths for the ears. However, the Scythian bow would leave no telltale

laths in the archaeological records. Even in the heartland of the Scythians,

modern Russia and the Ukraine, very few identifiable remains of bows remain.

Figure 3

Subeshi Bow and Sections (Not to scale)

Stephen viewed several bows in the Museum in

Urumqi. Two in particular recall Scythian bows of the West. Both were displayed

with bowstrings and arrows of about the right length [iii],

though they may not have originally associated with these particular bows.

Figure 4

Simplified drawing of bow tip from belly side showing string groove

Stephen measured one bow and found that it

measured about 130 cm around the curves and 119 cm in a straight line from one

end to the other. The centre of the set back grips is 53 cm from on end and 66

cm from the other. This is a straight-line measurement. The centre of the bow

was 4 cm wide and tapered to 3.5 cm at the mid-limb. The limbs were bound with

thread [iv]

below a layer of lacquer. If the materials are really silk and Chinese lacquer,

then the use of these materials clearly suggests Chinese craftsmanship. Silk

wrapped and lacquered bows have been excavated in Warring States and Han tombs [v].

However, the bow was found in a cemetery primarily containing people of

European features [vi].

Whether the bow was finished or recovered by a Chinese artisan or complete

constructed by one is hard to say at the moment. However, Stephen advised me

that the thread could not be identified under the layer of lacquer and the

nature of the lacquer itself has not been determined yet. The bow is dated

approximately 600 BCE, but may be later. The Scythians were prominent in the

West between 750 BCE and 300 BCE. After that time they went into decline though

enclaves survived into the current era in the Crimean peninsula.

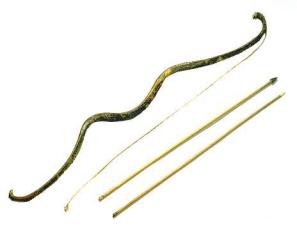

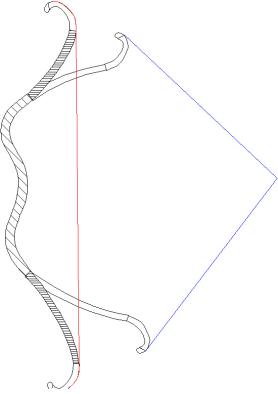

Figure 5

A Scythian style bow from Subeshi in Shanshan County, Xinjiang

Figure 6

A sketch of how a bow may have appeared strung and drawn

The sketch of the drawn bow is tentative and

almost certainly incorrect in detail. The bow would have had a greater bend

closer to the handle than I have drawn. However, the degree of this will need to

be determined by experiment. Scythian artwork often shows the parts of the limbs

I have crosshatched horizontally bent almost parallel to the arrow, as in a

Korean bow. Stephen’s

measurements of the bow indicate the stiffness of the bow was varied by reducing

the width rather than by changing the shape of cross-section. Judging by the

sections at the recurves, they may have been flexible enough to straighten out

partly at full draw. However, in art, the representations usually show a

prominent recurve at the tips when the bows are fully drawn.

Figure 7

A Western Scythian style bow reconstruction by David Betteridge

At least one of these bows was buried in a

combined bow case and quiver that the Greeks called a “gorytos” (γωρυτός

written gorytus in Latin). This piece of equipment was common from Scythia and

Greece in the West to Siberia in the East. Although there were obvious

variations between the Eastern and Western version of this equipment, they

shared a number of key features.

The quiver was attached to the outside face of

the bow case when the bow was pointing backwards.

About two-thirds of the bow was inside the case.

The arrows are usually slightly shorter than the

case, although the quiver portion of the gorytos can be shorter than the whole.

The main decoration of the gorytos is on its

outside face, the side to which the quiver is attached.

The bowstring was uppermost when the bow was in

the case unlike later bow cases for the strung bow.

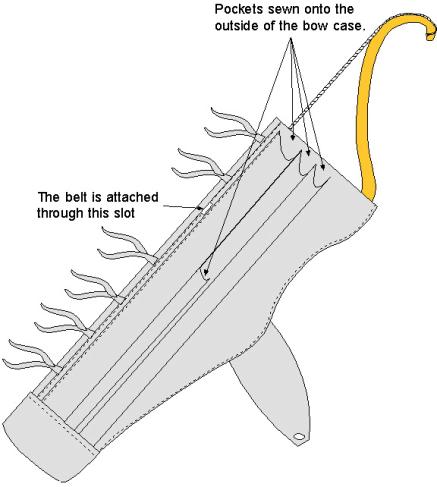

Figure 8

Drawing of a gorytos of the Eastern type

It is worth mentioning too that there are many

indications that a soft leather or cloth cover could be slipped over the upper

end of the bow to protect it from the weather. This would cover the top part of

the gorytos down to the suspension point. It is clearly shown on the Persepolis

reliefs and in many Greek vase depictions.

The leather tab on the bow case part of the

Urumqi Museum gorytos may represent another way the gorytos could be worn. If a

strap ran from the upper edge suspension point of the gorytos to the hole in the

tab, the strap could be slung over the left shoulder. This should make the

gorytos hang diagonally across the back and position the openings of both bow

case and quiver next to the right shoulder. This is pure speculation.

The Origin of the Scythians.

Warlike horse nomads are first mentioned in the West in

Assyrian documents in the eighth century BCE. These Cimmerians were eventually

over thrown by the tribes the Greeks called Scythians. They raided extensively

in the Near East and eventually allied with the Medes of western Iran to destroy

the Assyrian kingdom. According to the ancient historian, Herodotus [ix],

the Medes then murdered the Scythian leaders at a banquet and drove their forces

out of the Middle East. The Scythians retreated to the Pontic steppe through the

Caucasus. Reading the account of Herodotus, you might be excused for imagining

that the Scythians were a group of longhaired, bearded barbarians of a violent

and emotional nature, who drank the blood of their enemies and were addicted to

cannabis-laced sweat baths. However, there is much more to them than that.

The first nomads of the steppe north of the Black Sea

mentioned in the ancient historians were the Cimmerians who seem to have

originated in that area. They were early nomadic pastoralists who adopted a

stock raising, wandering lifestyle as an alternative to mixed farming. The

Scythians appeared from the east and started driving the Cimmerians before them.

The Cimmerians raided south through the passes of the Caucasus and ravaged

Anatolia. Some scholars believe that the Scythians originated in southern

Kazakhstan [x].

Therefore Scythian-style culture could have radiated east and west from a common

centre.

The Scythians were predominantly horse archers. Because

of the vast area they dominated, archaeological evidence for them is

geographically dispersed. So much so, that it would be difficult to prove racial

or linguistic uniformity, even though we can see lifestyle and artistic

continuities between these sites.

At one end of the geographical range, gold vessels

provide illustrations of the horse gear and equipment used, while at the other

end frozen tombs provide actual saddles, bridles and the corpses of horses.

Herodotus wrote about their daily life and, until the discoveries at Pazyryk in

the Altai Mountains, he was generally believed to be unreliable about the

Scythians. However, many strange details of his narrative have proved to be

true, such as hemp-enriched steam baths and the habit of scalping their enemies.

The Scythians and people in Scythian dress were widely

depicted in Ancient Greek art. The Achaemenid Persians [xi]

included eastern Scythians (the Sakas) among the tribute bearers in the

bas-reliefs at Persepolis [xii].

The bows discovered in Xinjiang are as important to the study of archery as the

frozen tombs in Pazyryk were to the general studies of the Scythians. Until

these discoveries were made, only fragments of Scythian bows and representations

could be studied. Of archery equipment, only metal fittings for the gorytos, a

combined bow case and quiver, arrowheads and a few parts of arrows survived. (I

have not included any illustrations of the typical Scythian three-bladed, bronze

arrow heads here because I do not know if any have been found in association

with these bows.)

The typical Scythian warrior was a horseman who used

archery as his prime offensive weapon. On his left side he wore a gorytos. The

arrows were typically tipped with two or three-sided bronze arrowheads. At the

western end of the steppe the arrows that survived were usually between 55 and

60 cm long [xiii]. At Pazyryk, however,

broken arrows were reassembled to suggest a length of 80 cm. From western steppe

tombs, large gold plates were excavated which were evidently the covers of the

outside faces for the wood and leather gorytoi. In art, the gorytos was usually

two-thirds to three-quarters the strung length of the bow. The gorytos plates

for which I have measurements are about 45 cm long. The whole gorytos was

probably about 55 to 60 cm long, making it about the length of the arrows found

in the same area.

Figure 9

Simplified view of a Western Scythian Gorytos.

Another characteristic feature of the Scythians was

that they used an early form of saddle. This basic saddle consisted of two

quilted, stuffed cushions sewn to a cover with a gap down the centre between

them. Each cushion was reinforced and decorated on its front and rear faces.

This helped keep the front and rear of the saddle higher than the middle. A

strap was attached at the front and another at the rear of the cushions to

reinforce them and cover wooden spacers than kept the cushions apart. A third

strap went over the centre of the saddle and it was used to attach the girth and

the breast strap. There were no stirrups and no rigid tree to hold the shape of

the saddle. However, it was a great improvement of the basic saddle blanket,

which had been its predecessor. A felt pad was sewn underneath it and it was

usually covered with a decorative saddle cover.

These saddles are depicted in Scythian gold and silver

work from Russia and the Ukraine, in Siberian gold buckles, and on the pottery

horses of Qin Shihuangdi’s cavalry. Real examples were found frozen in the

tombs of Pazyryk [xiv] and a dried-out saddle [xv] near the burials of our

bows and gorytoi.

The Medes and some Persians are shown in the Persepolis

reliefs wearing gorytoi that are longer than those of Saka tribesmen in the same

group of reliefs. In both cases, there is a cover over the projecting part of

the bow, so details of its shape other than its profile are impossible to see.

The exception is that there is some detail of the recurvature of the bow because

the bow was strung and carried belly-up. The soft cover of the bow shows a

rounded profile. In the same group of reliefs other Persian soldiers are shown

using a longer bow without a setback handle. They carry a large shoulder quiver

instead of the gorytos.

In the collection of the Urumqi museum there are bows,

arrows and gorytoi of the longer eastern type, but obviously related to the

western Scythian equipment. Some features of the gorytos are similar to one

depicted in an architectural decoration in the old Parthian capital of Nysa in

Central Asia. Of particular interest is the use of multiple pockets for the

arrows on the outside face of the gorytos.

Some of the gold gorytos plates from Russia have

surviving bases in the form of an elongated teardrop with the narrow end facing

upwards. There is usually a ridge down the centre of the base showing the

separation of the bow case and quiver sides of the gorytos. The gorytos in the

Urumqi museum [xvi] has only a supporting

wooden rod rather than the two- or three-sided wooden frame implied by the

shapes of gorytoi in Greek and Scythian art and the gold plates with their

bases. The Nysa gorytos looks more like the Urumqi example because it has a

rounded base rather than the flat one of the Western types. This is also true of

the gorytoi on the Persepolis bas-reliefs.

The Scythian Bow.

There is a complex of weapons associated with the

Scythian lifestyle. They include the bow, arrows and gorytos. In the West the

arrows almost always had socketed, three-bladed heads and were made of bronze [xvii].

There is also a short sword called by the Greeks, an akinakes, which was worn on

the right side with the chape of the scabbard sometimes tied down to the right

thigh. Another common weapon is a narrow-bladed battle-axe with some resemblance

to the Chinese dagger-axe (ge) and ancient Near Eastern weapons. Spears and

javelins are also common in tombs. Increasingly discoveries in Eastern Europe

are adding weapons and armour to this catalogue. The use of scale armour is much

more prominent than once thought and long two-edged swords are also more

frequent.

The shortness of the bow is

an obvious convenience. Though much is made about the usefulness of short bows

on horseback, the early horse archers depicted from Assyria have medium-sized

triangular composite bows, which they drew to the right shoulder. The Qing

dynasty Manchus and the Japanese, used quite long bows and long arrows in the

last period of military horse archery. So the convenience of a short bow could

easily be overridden by other factors such as the ability to deliver a large

heavy arrow. The Assyrians moreover did not even have the advantage of the basic

saddle of the Scythians, but instead used a saddlecloth. However, the gorytos

did enable easier mounting without stirrups. It is always shown with the bow

pointing backwards when it is in use. Another feature of the short bow in the

West is the large number of arrows carried in the gorytos. The tiny bronze

arrowheads are found in numbers above fifty with the remains of gorytoi in the

Ukraine.

The recurved tips are a new

development in archery at the time, though you can see that they had ancestors.

The Assyrians and Elamites used triangular composite bows with bird’s head

shaped nocks for the strings. Since the string loop had to attach to the

bird’s beak on the back of the bow some form of basic groove was probably

carved in the tip of the bow to lead the string over. Prior to that narrowing

the tip of the bow abruptly to make two shoulders formed the string nock. On

some Ancient Egyptian bows this was carried to the extreme of having the nocks

of the bows carved into representations of Pharaoh’s enemies, their shoulders

the shoulders of the nock, their head the peg-like nock itself. Every time the

king drew his bow he strangled two of his enemies in effigy [xviii].

Figure 10

View of an Ancient Egyptian bow tip

Figure 11

View of a late Assyrian bow tip.

Figure 12

View of the tip of a bow from the Achaemenid palace at Susa.

Figure 13

View of the tip of the bow from the Urumqi Museum

Set back centre sections have

been used in many places at many times, but before the introduction of the

Scythian bow, they were usually the characteristic of a bow that was under

braced. They were used to increase the bow’s power stroke on the arrow by

bringing the belly of the handgrip closer to the string. Under braced self-bows

were designed to reduce the stress on the braced bow, prolonging its life. In

the Scythian bow, they were probably introduced to shorten the draw, while still

maintaining an optimum amount of limb bending. Then

you could carry more but shorter arrows and still get good performance out of

your bow. Another effect was to increase the physical

length of the bows while retaining a short “strung’ length.

Figure 14

Cross-section based on parts of a Scythian bow from

the Three Brothers Kurgan and fragments from Sivush.

The fragments of a western

Scythian bow from the Three Brothers Kurgan [xix]

have a circular cross-section of three layers wrapped in birch bark. Other

fragments of bows are similar [xx].

This is consistent with a derivation from the ancient Near Eastern bows. Most of

the bows from Tut‘ankhamūn’s tomb are much thicker compared to their

width than we would now make a bow. While they have some reflex [xxi]

in their unbraced state, they have nothing like the reflex seen in later

composite bows. The various Greek representations of Scythians and Greeks

bracing their bows show positions that would not work with bows that are very

reflexed.

The Egyptians had separate

bow cases for their bows mounted on their chariots, but the Assyrians just

stuffed them into their quivers. In both areas, the quiver was worn on the back

when it was not attached directly to the chariot. At some stage, someone decided that a bow case attached to a

quiver would be a good idea. With the small Scythian bow and arrows, the

resulting object was not too unwieldy. The advantages were obvious: the bow was

protected from the weather and the points of the arrows.

The case also prevented the bow from being distorted, yet it was ready to

hand already strung. Drawing short arrows across the body was no great trouble

(the Plains Indians in America, when they reinvented mounted archery did a

similar thing). However, that brings us back to the Urumqi bows. Their arrows

were not short and there is some evidence that even in the West these larger

Scythian bows were in use [xxii].

The Urumqi gorytoi [xxiii]

are almost a metre long (90 cm) and the arrows are about 80 cm long. So too were

the arrows from Pazyryk. The Siberian gold belt plaques show people drawing to

the ear. Perhaps they were nearing the outer edge of utility for a gorytos.

Coupled with this large size, these gorytoi do not seem to hold as many arrows

as the smaller Western ones. This could mean that the archers needed fewer

because their larger arrows were more effective. It could also mean these were

hunting quivers and they did not have to carry many arrows. The arrows had a

mixture of wooden, horn and metal tips.

The Scythians at War.

The Scythians were primarily cavalry fighters. They

rode into battle and fought on horseback. Herodotus describes their tactics when

fighting the Persian army led by Darius the Great. They used traditional

scorched earth tactics and retreated before the large Persian army, successive

leading the Persians through each of their subject states so that their own

lands were not ravaged. After various taunts directed at the Persians, they

informed Darius that they would stand and fight if the tombs of their ancestors

were desecrated. This was the last straw for the Great King [xxiv],

who turned around and went home. Scythian horse archers had consistently

prevented the Persian army from foraging and had left Darius little choice.

This was a tale of frustration from the Persian point

of view. The Scythians effectively contained the largest army of the Middle East

and actually used it to do their own dirty work by punishing their less

enthusiastic allies. Lest we underestimate the Persians, remember that they

transported this large army from Persia through Anatolia, across the Bosphorus

on a bridge of boats, through Thrace and onto the steppe lands of Eurasia. The

logistical skills, with which they consistently underpinned their great military

expeditions, are really remarkable. However, they were outmanoeuvred by the

Scythians and confined by their swarms of horse archers.

Against a smaller army, the Scythians could be much

more aggressive and use their weapons more directly. In later years, they were a

thorn in the side for Macedonia and it took Alexander the Great to defeat their

king, Ateas. This combination of effective archery and speed of manoeuvre led to

an arms race on the steppe. Armour became popular and the Scythians themselves

eventually became victims of their more heavily armoured relatives, the

Sarmatians [xxv].

These bows are significant for two separate reasons.

They provide use with examples of how an early type of bow looked and will

eventually help us learn how it was constructed. They also show us how

widespread the Scythian steppe culture was and how the Chinese were able to

absorb some of its technical innovation. If I have spent so much time on the

Scythians, it is because this archery evidence of their presence so far east is

remarkable and it shows that the great civilisations of the world were not as

isolated from each other as we often think.

Some Questions.

There are several questions raised by these bows and

their associated equipment.

·

How were they shot? What technique was used to

draw the bow?

·

How were they constructed? What materials were

used?

·

How effective were they? How did they perform?

·

Who made them and did they influence other bows?

·

What is the relationship between the people who

were buried with these bows and the various groups living a “Scythian”

lifestyle?

Various theories have been advanced about how the

Scythians in the West shot their bows. My opinion is that the most likely is a

variation of the Mediterranean release called the Flemish release where the

index and middle fingers draw the string with the nock of the arrow between

them. I think that the existence of armguards (bracers) in some later tombs in

the area supports this view. The Western bows were so short that this grip was

necessary. Some authors have suggested a Primary Release or a Secondary Release

could have been used, but the primary release is not very strong and the

secondary is clumsy with a very short bow.

However, the bows in Xinjiang are 50% larger and not so

restrictive on the position of the fingers. In fact, there are several features

of them that generate other problems when shooting. The centre section of the

bow is 4 cm wide and would be quite a handful for most people. The

archaeological evidence suggests that the people in the cemeteries were quite

large [xxvi]

and perhaps were not inconvenienced but the large cross-section of the bow.

Unfortunately, there are no X-Rays of these bows yet

and we do not know their construction. The majority of bows seen by Stephen were

in such good condition that their internal construction is undetectable. The odd

triangular cross-section of the bow in its central parts may reflect the shape

of the horn available [xxvii]

or it might be something else entirely. There is always the possibility that the

bows are meant as grave goods only, merely full sized models of weapons. In that

case we are only looking at the form of the original. Some comments [xxviii]

can be made however. The complex shape of these bows is not likely to be

accidental or the result of parallel evolution of designs.

The most likely construction is a horn-wood-sinew

composite. The cross-section of the bow would put very high stresses on the

belly of the bow. Even with the reduction of reflex that Betteridge advances in

an upcoming paper, composite structure is about the only way to make this bow

work effectively. Of course modern bowyers could combine diverse technologies to

achieve a workable bow, but these were not available to the dwellers of Central

Asian oases before the current era.

The binding of the bow would make a major contribution

to its strength. The many changes of curvature increase the risk of the

laminations of the bow separating from each other. In modern Mongolia, some bows

are bound from end to end with transparent thread like fishing line to prevent

de-lamination. In was common in later periods to bind points of high stress with

sinew in glue as with the section of the much later bow Stephen brought back

from Xinjiang. Other resins aside from Chinese lacquer could have been used to

waterproof and protect the sinew. We will not know until one of these bows is

subjected to much more intense study.

Another part of Betteridge’s analysis implies good

performance for this shaped bow. Historical evidence mentioned above also

supports the contention that the Scythian style of bow was effective in hunting

and war. Several people already have made reproductions of Scythian bows, but as

more material is published on the Xinjiang bows, their next bows will be more

useful for estimating the range and efficiency of these ancient bows. It is up

to the bowyers to expand our knowledge in this area and I do not doubt that they

can.

I think it is likely that the bows were made locally,

but the future studies of the artefacts themselves could reverse this view.

Perhaps the materials were imported in part. Maybe Chinese craftsmen applied

lacquer and binding to previously built bows to increase their durability. At

the moment, there is just not enough evidence.

If the local people made the bows, it is likely they

represent the eastern extension of the Scythian lifestyle. However, whether this

supposition is true or the people in this area simply used bows copied from

their more nomadic neighbours is a question that requires further research. If I

use a Turkish bow, it neither makes me a Turk nor proves that I am influenced by

Turkish culture in general. I might think it is a good bow and I might even

learn to make my own.

These bows’ influence on the construction other bows

depends on their exact dating. A bronze model crossbow from the tomb of Qin

Shihuangdi [xxix] has a setback centre

like these Scythian style bows, but was it the result of influence or

convergence? It did not have recurved ends. Later bows were made with setback

handles for many centuries. However, the recurved ends of the bow were lost in

the Old World of Europe, Asia and Africa until American bowyers reintroduced

them in the 20th century. The closest bow in appearance is the Korean

composite bow, but that has a long history of its own. The extreme reflex of the

Korean bow and its entirely different cross-sections rule out much historical

connection. Though many elements of steppe culture entered the Korean peninsula

and were absorbed by the local culture, it is unlikely that this bow is

responsible for later developments in Korean archery, which probably has more to

do with native traditions combined with Ming Chinese influence.

Conclusion.

The presence of Scythian-style equipment in a cemetery

on the frontier of China is not surprising in itself. The presence of the

mummified remains of people with Western features in the area is now well known.

What is exciting from the point of view of archery is that a group of complete

early bows has been preserved. The burials in various graveyards in the

immediate area contain a range of archery equipment from various times. Because

of the widespread Scythian nomadic culture, its interaction with the various

large states on the periphery of the Eurasian steppe is significant not just for

what it says about the Scythians and their relatives. The states on the borders

of the nomadic world reacted to the threat and the military technology of their

warlike neighbours. These reactions both provide insight into the nomads and

their settled neighbours.

While the bows themselves are clearly in the orbit of

Scythian culture, if the finish is lacquer and binding, then it is closely

related the Chinese technology. In Pazyryk, the same mix of influences is

visible. Chinese mirrors and fabrics are combined in tombs with Scythian

animal-style artefacts and Near Eastern carpets. We do not know all the answers

now, but discoveries like this by archaeologists are helping us learn more. At

this stage of the investigation of the early inhabitants of Shanshan County, we

cannot be sure whether all the people buried in these cemeteries were locals or

travellers who died there. Even the dates are not precise yet. No one can

predict what will be found next in China, Siberia or Russia. Nor do we yet know

what will be discovered when more research is carried out on these amazing

artefacts.

Archery was bound up with the everyday lives of many

ancient cultures and in these bows we can see a technological bridge between the

East and the West. The Scythians and the Saka and their various relatives and

imitators represent the first major exponents of mounted pastoralism known from

history. It is entirely appropriate that their choice in bows should be so

distinctive and innovative.

Acknowledgements.

I would like to thank Stephen Selby for letting me

examine the photographs of the bows and who originally found the book from

Xinjiang mentioned below for me. David Betteridge and I have long discussed the

development of ancient composite bows and he had already started making replicas

based on the artwork and Russian excavation reports before Stephen’s

investigation. He also permitted me to use a photograph of one of his

reconstructions in progress and lent me some of his research. Edward McEwen, who

discussed also the design of the bows, provided me with the first photograph I

had seen of one. Adam Karpowicz was responsible for me seeing Chernenko’s book

and had also given me insights into the technical problems.

Further Reading.

See the Brooklyn Museum of Art for an

illustration of a gold gorytos cover.

http://www.athenapub.com/8goldnom.htm

See the Wesleyan University site for a Greek

representation of a Scythian archer holding a bow.

http://mkatz.web.wesleyan.edu/grk101/linked_pages/grk101.scythian_archers4.html

Bibliography

Andrakh, S. I., A BURIAL SCYTHIAN WARRIOR IN THE

SIVUSH AREA, 1988:1, pp. 159-170, Soviet Archaeology. (In Russian with English

summary.)

Brentjes, Burchard, WAFFEN DER STEPPENVÖLKER

(II): Kompositbogen, Goryt und Pfeil – Ein Waffencomplex der Steppenvölker,

Band 28, 1995-1996, pp. 179-210, Archaeologische Mitteilungen aus Iran. (In

German.)

Cernenko, E. V., THE SCYTHIANS 700-300 BC, 1983,

Osprey Publishing Ltd

Chernenko, E. V., SKIFSKIE LUCHNIKI, 1981,

Naukova Dumka, Kiev. (In Russian.)

Christian, David, A HISTORY OF RUSSIA, CENTRAL ASIA AND

MONGOLIA, Volume I, 1998, Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Dubovskaya, O. R., A BURIAL OF AN ARCHER,

1985:2, pp. 166-172, Soviet Archaeology. (In

Russian with English summary.)

Herodotus, THE HISTORY, various translations.

Mair, Victor, (Editor), THE BRONZE AGE AND EARLY

IRON AGE PEOPLES OF EASTERN CENTRAL ASIA, 1998, Monograph No. 26, University of

Pennsylvania Museum Publications, ISBN 0-941694-63-1

Mallory, J. P., and Mair, Victor H., THE TARIM

MUMMIES Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West,

2000, Thames & Hudson, London.

McEwen, Edward, Miller, Robert L., Bergman,

Christopher A., EARLY BOW DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION, 1996, Scientific American,

June.

McLeod, W., COMPOSITE BOWS FROM THE TOMB OF TUT‛ANKHAMŪN,

1970, Tut‛ankhamūn’s Tomb Series, III, Griffith Institute, Oxford.

Phillips, E. D., THE ROYAL HORDES Nomad Peoples

of the Steppes, 1965, Thames and Hudson.

Rudenko, Sergei I., FROZEN TOMBS OF SIBERIA The Pazyryk

Burials of Iron Age Horsemen, 1970, J. M. Dent and Sons Ltd, London, originally

published in Russian in 1953.

Wang Binghua (Editor), THE ANCIENT CORPSES OF XINJIANG,

2001, translated by Victor Mair Xinjiang People’s Press, ISBN 7-228-05161-0

Yang Hong, WEAPONS OF ANCIENT CHINA, 1992, translated

by Zhang Lijing, Science Press, New York and Beijing.

Zhuo Xuejun and Ma Chengyuan (Editors), ARCHAEOLOGICAL

TREASURES OF THE SILK ROAD IN XINJIANG UYGUR AUTONOMOUS REGION, Shanghai

Translation Publishing House.

NOTES

i]

The Scythians referred to here are also called Saka by the Ancient Persians

of the Achaemenid dynasty. In Latin this became the Sacae. Though these

people were related in life styles and in language, they probably saw

themselves as distinct as the Turks and Mongols do today. It is easy from

the perspective of two millennia to see things as similar that might have

been very distinct in their time.

[ii]

“Siyah” is an Arabic word used to describe the rigid ends of a Middle

Eastern composite bow. Usually siyahs had different cross-sections than the

bending sections of the limbs. Unlike the ends of modern Korean bows there

was little bending in a siyah.

[iii]

By “right” length I mean lengths calculated from both representational

evidence, mathematical formulae and experience with other bows. The various

reports on the finding of these bows suggest they were often found with

their strings.

[iv]

Stephen suggests this could be silk. Silk binding and lacquering of bows has

been reported from China in the Warring States period. Even staff weapons

could have their shafts reinforced in that manner.

[v]

See WEAPONS OF ANCIENT CHINA, pages 95-96, where bows made of layers of

bamboo wrapped in silk and lacquered are described from Eastern Zhou tombs.

[vi]

See THE ANCIENT CORPSES OF XINJIANG, page 109, where the contents of tomb M4

cemetery No. III (3) are described briefly and there is a photograph of a

bow and arrows.

[vii]

Unfortunately for copyright reasons we cannot use both photographs, but the

bows are very similar and the drawings are a reasonable guide.

[viii]

One from Stephen Selby’s collection is illustrated on the ATARN website (www.atarn.org),

but the unusual grasp might be explained by the fact that the bow is being

used to shoot pellets.

[ix]

Herodotus of Harlicanassus in Asia Minor is sometimes called the father of

history in the West. His great book was full of ethnographic details.

Several other Greek authors wrote about the Scythians, but there is little

detail on archery.

[x]

David Christian has an excellent bibliography in A HISTORY OF RUSSIA,

CENTRAL ASIA AND MONGOLIA, which makes it much easier to look up the various

opinions on the origins of the Scythians.

They are generally thought to be Indo-Europeans speaking some sort of

Iranian language. However, the bodies from Pazyryk show both Caucasoid and

Mongoloid physical features in one population.

[xi]

Cyrus II (ruled circa 559-525 BCE) of Persia founded the Achaemenid Empire

(circa 559-330 BCE) after conquering the Medes. He was killed fighting the

Massagetae in Central Asia, neighbours of the Saka. The empire fell to

Alexander the Great several centuries later.

[xii]

Persepolis was a ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid dynasty in the

province of Persis, now Fars in Iran. Mainly Darius and his son Xerxes built

it. The surviving parts are decorated by detailed bas-reliefs of the

ceremonies that took place there. Representations of most of the peoples of

the empire have survived and their clothing or the gifts they bring to the

Great King often can identify them.

[xiii]

See A BURIAL OF AN ARCHER, SKIFSKIE LUCHNIKI and A BURIAL SCYTHIAN WARRIOR

IN THE SIVUSH AREA.

[xiv]

See FROZEN TOMBS OF SIBERIA, Chapter 6, Means of Locomotion.

[xv]

See ARCHAEOLOGICAL TREASURES OF THE SILK ROAD IN XINJIANG UYGUR AUTONOMOUS

REGION, page 105. Plate 27 and page 255 for the saddle excavated from Tomb

No. 3 of No. 1 Graveyard at Subeixi, Shanshan County, Xinjiang.

[xvii]

There is a considerable literature on these arrowheads. In the past

Soviet archaeologists have elaborately recorded their many variations.

Speculations on how they were cast and the efficiency of their production

have been fuelled by finds of moulds and unfinished arrowheads still

attached to their sprues. Some details of the procedures can be found in

SKIFSKIE LUCHNIKI. An arrow shaft generally had a small tenon carved into

its end, which fitted into the socket of the arrowhead. These heads were

small and strongly constructed though some of the sockets were only 4 mm

wide internally.

[xviii]

See COMPOSITE BOWS FROM THE TOMB OF TUT‘ANKHAMŪN, Plate XV for

examples of 21 bow tips from Egyptian tombs for more detail.

[xix]

See SKIFSKIE LUCHNIKI, page 9, Fig. 1, showing part of this bow. It may have

only been a model weapon. My cross-section is derived from this

illustration.

[xx]

See also the article in Soviet Archaeology, A BURIAL SCYTHIAN WARRIOR IN THE

SIVUSH AREA.

[xxi]

By reflex, I mean the curvature towards the back of the bow that appears

when it is unstrung. By recurve, I mean the curvature of the tips of a bow

towards the back when it is strung. These terms have been used in this

fashion in archery literature for a very long time, but occasionally they

are confused in non-archery writings. The same thing happens with the terms

composite and compound. The first means put together from separate

components like horn, wood, and sinew. The second originally meant bows made

of similar materials glued together, such as Japanese bows and some bows

from Mediaeval Russia. Nowadays it means a bow with mechanical attachments

such as eccentric pulley wheels, while the old compound bows are referred to

as being laminated.

[xxii]

Some Greek vases clearly show large Scythian bows being drawn to the ear.

The normal draw shown in the West for Scythians was only to the left nipple.

While later authors derided this short draw, it was effective at the time

and allowed for rapid shooting.

[xxiii]

See ARCHAEOLOGICAL TREASURES OF THE SILK ROAD IN XINJIANG

UYGUR AUTONOMOUS REGION, page 104, Plate 26, and page 254, for a clear

photograph and description of a gorytos associated with a bow and arrows

from Tomb No. 2 of No. 3 Graveyard at Subeixi, Shanshan County.

The bow was 121 cm long, the arrows 82 cm and the gorytos was 93 cm

by 30 cm at its widest.

[xxiv]

The Persian Emperor was called the Great King, which is a literal

translation of one of his titles. In Greek this was rendered as

‘basileus’ or king.

[xxv]

The Sarmatians have an interesting history. Herodotus referred to the

Sauromatae as the eastern neighbours of the Scythians. Whether the

Sauromatae had a name change or the Sarmatians were a sub-tribe of a

confederacy is not really clear. Several authors have contributed ideas on

the subject, but it is really beyond the scope of this article. The

bibliography of David Christian’s book has many useful references to this

problem.

[xxvi]

See THE ANCIENT CORPSES OF XINJIANG, pages 103-109, for descriptions of the

bodies. The men were sometimes over 1.8 metres tall. This evidence is

discussed in an accessible way in THE TARIM MUMMIES Ancient China and the

Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. I must point out that in

Sarmatian burials, archery equipment is sometimes found in female interments

too. While I have not found evidence of this practice in Xinjiang, it is

possible that bows have been found with female bodies or that they might be.

Not having read all the published material on the graves, I am at a

disadvantage in this area of discussion.

[xxvii]

This view came from a discussion I had with David Betteridge. It was based

on the likely availability types of horn in the area. Also we discussed the

logic of the design of Scythian and the Middle Eastern bows, which preceded

them in the West. These were usually as wide as they were thick. In Egyptian

bows, the horn was not always the full width of the belly of the bow because

it was inset in a channel. The relationship of these designs to the flatter,

bamboo-based bows used in the Eastern Zhou states in China is beyond the

scope of this article.

[xxviii]

These comments are based on conversations with David Betteridge regarding

the design of Scythian bows in the West and their relationship to the bows

discussed in this article. Over several years we have been researching the

development of early composite bows. Stephen Selby has been revealing the

discoveries in Urumqi and this has made a significant contribution to our

study.

[xxix]

Stephen Selby has discussed elsewhere (http://www.atarn.org/letters/ltr_feb99.htm)

the possibility that Chinese crossbows may have used hand bows for their

prods. A feature like a setback centre section has little point in a

crossbow, but has some advantages in a hand bow. This is an additional

argument for Stephen’s thesis.

Page last up-dated on 19 March, 2004