Text and Illustrations © Bede Dwyer, 1997.

PREFACE

The original version of this article was published in the Journal of the Society of Archer-Antiquaries, Volume 41, 1998. Since its publication, I have learned that Chinese archaeologists in Xinjiang have excavated intact gorytoi and other early archery equipment, which supports the accuracy of contemporary representations. The future might bring similar exciting discoveries for the later quivers discussed below. I have not attempted to reproduce the colours and patterns in detail of the original illustrations on which I based my drawings. I recommend examination of sources in the notes to anyone who wishes more exact information.

INTRODUCTION

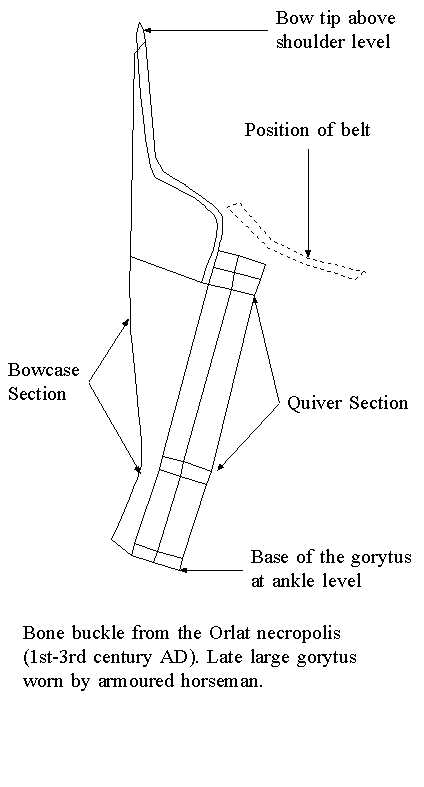

The horse riding nomads of the Eurasian steppe lived in a harsh environment made more difficult by their sometimes hostile relationships with their more sophisticated neighbours to the South and West. Subject to the extremes of a severe climate and the limitations of their technology, they had to develop solutions to the special problems of maintaining and carrying their weapons. When the Scythians burst onto the world stage in the eighth century BC, they already had their characteristic quiver and bow case combination, the gorytus, developed to overcome the particular problem posed by archery equipment. This protected the arrows and the bow in a single case, with the arrows on one side of a partition and the bows on the other. One excavated example appears to have had a small flap on the quiver side to close the top of the quiver area completely. Even that portion of the bow exposed outside the case could be covered by a piece of waterproofed felt or leather, as depicted in paintings on Greek vases and the reliefs at Persepolis. This combined bow case and quiver sufficed while the arrows were short, but a gradual trend towards longer draws initially led to both longer arrows and longer bows(1). Longer bows and longer arrows diminished the utility of the gorytus, which can be seen when looking at the stucco architectural decoration in the shape of a gorytus from Nysa(2), the old Parthian capital, and later engravings on bone belt plaques from Central Asia(3).

The kings of Iran of the Sassanian dynasty (224-642) were famous archers. Sassanian silver plates sometimes show the kings hunting using long tapering quivers worn on the right side and hanging from the belt. None in the first half of the dynasty show any form of bow case when the left side of the king is visible. It may be argued that the Sassanian quivers are related to the last gorytus design from Soghdia, but they are probably an independent invention. However, both the gorytus and the shoulder quivers of the ancient world followed an implicit concept of arrow storage: that arrows should be stored with their points in the base of the quiver and their nocks accessible to the archer's hand.

I have coined the name "closed quiver" for the subject of this article, which differed in this primary respect from the preceding quivers: the arrows were stored with points uppermost in a container that could usually be completely closed off from the elements. Obviously it is no more closed, for instance, than the Archaemenid Persian quiver shown in the reliefs at Persepolis or for that matter the quiver portion of the gorytus, but one of its unique features is a small door, hinged at its base, on the outside face of the quiver at its top. The closed quiver usually hung from a belt around the waist with its upper end pointing forward. At the time of its currency, there was another quiver in general use, which I shall call the "open quiver" to contrast it with the main topic of this piece. This other quiver is a descendant of the Sassanian and Chinese cases, where the fletching of the arrows is exposed, and the upper end of the quiver invariably points backwards at an angle.(4)

REPRESENTATIONS OF QUIVERS

Quivers are represented in art on many media. Incised line drawings on bronze and deep reliefs on stone vie with delicate paintings on silk and detailed wooden models with painted arrows depicted in them. However, I must voice a word of warning: what is drawn by an artist in a traditional culture is not necessarily what he saw, but what he thought should be there. In the painting of the Islamic world, pounces(5) were used extensively and archaisms could easily creep into an artist's repertoire. In China in the East and Byzantium in the West, anachronistic features were often included in paintings to impress the viewer with the learning of the artist or to evoke a mood of antiquity. Sometimes alien art forms were imitated or adapted because of fashion and the attempt to make sense of some features created imaginary objects. A case in point is the paintings in the Topkapi Sarai Museum attributed to Siyah Kalemi (Black Pen), which often contain detailed and realistic renditions of imaginary objects juxtaposed with perfectly normal ones(6).

Having said that, much is accurate and useful in the various paintings and other representational art that have survived from the past. In some details, art has been confirmed by archaeology. In others, it poses more questions than can be answered with the material at hand. Some information can only be derived from art, like how a quiver belt was worn while walking as opposed to riding.

The figures presented in this article are drawings based on various sources mentioned in the notes, but the quivers are abstracted from their contexts and may appear slightly distorted. Their belts are generally shown by dotted lines. The quivers are shown hanging at the angles they had in the original artwork, except for archaeological examples. The paintings that these figures are based on were never intended to be blueprints, but they are very instructive.

EARLY DEPICTIONS OF CLOSED QUIVERS

The earliest depictions of closed quivers that I can find predate the use of stirrups on the steppe, but are contemporaneous with the use of a tubular bow case for the unstrung bow. Horsemen often have developed cases for their bows as well as their arrows, but there is a point in time probably after the second century AD, after which a bow case on one side of the belt and a quiver on the other became the standard equipment of the Old World horse archer. Armoured horsemen without stirrups are shown in a fresco from Kyzyl found by Albert von le Coq(7). They are each equipped with a quiver and a narrow bow case.

The early Tang Dynasty tomb of Li Shou at Sanyuan in Shensi(8), shows both open and closed quivers in a dramatic hunting scene painted on a wall in 630 A. D. However, the detail is not as fine as the later tombs and the quiver is presented only as an outline filled in black. Stirrups were being used in China at this time and are shown in other paintings in the tomb.

Chinese tomb reliefs show a completely developed closed quiver in the seventh century. The tomb of the second Tang Emperor (626-649 AD) was adorned with detailed bas-reliefs of his favourite chargers. One depicts his general, Qiu Xinggong, removing an arrow from the chest of the horse, Saluzi(9). Hanging at the general's right side is a perfect rendition of a closed quiver with both the arrow heads shown and the structure of the quiver detailed. The open flap of the door is shown in such a fashion to suggest its rigidity and the fact that it covered part of the top of the quiver and the side opening. A band between the base of the lid of the quiver and the mouth might represent a soft leather hinge. Two straps going to the general's waist belt are shown attached to fittings on the quiver. The outlines of reinforcing rods can be seen on both edges and the centre of the outside face of the quiver. A large tassel hangs next to the mouth of the quiver which is possible horse or yak hair like the tassels used to decorate horses' harnesses until recently in Northern and Central Asia. While the purpose of this attachment may seem obvious to a modern archer, in a wall painting in Li Xian's tomb (771 AD), a guard is shown pushing a tassel into the mouth of his quiver(10). This suggests that the tassel was to stop the arrows from rattling rather than to clean their shafts as in the modern practice.

Another painting from this tomb shows a hunting party galloping across a landscape of isolated rocks and trees. Quivers and the tops of tubular bowcases are well represented with the quivers always open. The quivers in these wall paintings are often painted black with red detailing. These are two common colours added to Chinese lacquer, so perhaps the quivers were protected with lacquer from the weather. It is also interesting that the quivers in these official scenes are often shown opened and empty of arrows. This may reflect a Court protocol designed to protect the Emperor or to show the innocent intent of the envoys.

At the other end of Asia, the great rock-cut figure of the Sassanian Shah, Khusrau II (Parviz), in armour at Taq-I-Bustan(11) also bears a fully developed closed quiver. This detailed portrayal of an armoured warrior shows how the low slung closed quiver stayed out of the way, while the king wielded his lance and shield. Elsewhere in the hunting bas-reliefs in this grotto, quivers are not in evidence and the king is handed arrows by an attendant while shooting. When riding, he wears his bow horizontally around his neck with neither quiver nor bowcase visible. Khusrau II (591-628) had close ties with Byzantium and particularly with the Emperor Maurice, who helped him gain his throne. In his father's reign (Hormuzd IV 579-590 AD), Iran had been fighting both the Khazars in the North and the Turks in the East and as a result it is not yet possible to say when and from where the closed quiver was introduced. Even after the Arab conquest of Iran, long open quivers, which cover the arrows up to their feathers, were still being depicted in wall paintings(12).

Warriors travelling and engaged in battle carry long, narrow closed quivers in the wall paintings from the Central Asian city of Piandjikent(13). Art historians see these paintings as representing the story cycle of the famous Iranian hero, Rustam. They date from just before and just after the Arab conquest in the seventh century.

DEPICTIONS IN THE MIDDLE AGES

The period equivalent to the Middle Ages in Europe saw a flowering of pictorial art in Iran and this produced some wonderfully detailed paintings during the Ilkhanid and Jalayarid dynasties. The "History of the World" of the Ilkhanid vizier, Rashid-ed-Din, was first illustrated in the early fourteenth century and the copy in Edinburgh(14) depicts many types of closed quivers showing structural variations and different materials (panels of birch bark stand out).

The fragments of a later Shahnameh, known as Hazine ("treasure") 2153 in the Topkapi Museum(15) show both open and closed quivers being used in battle. Fine details in the paintings suggest that the quivers may have sometimes been gilded and lacquered leather. Other albums contain pictures of figures wearing, or carrying, closed quivers of a form like a tapered cylinder with a domed top(16).

North of Iraq and Iran in Kubachi in the Caucasus, closed quivers are depicted in reliefs on stone panels from an eleventh century mosque(17). The quiver forms look similar to later Mongol quivers, which were equally large and broad based. The figure of a lone horseman in an arch bears a quiver with a vertically fluted body and an open lid. While in a panel with three scenes, pennoned lance, shield, quiver and bowcases stand beside two warriors wrestling. In the next scene, an archer turns and shoots over his horse's rump. The quivers in these scenes are broader than the more elegantly proportioned one worn by the horseman in the arch.

In China, in the ninth and tenth centuries, paintings showing closed quivers are still common and encyclopaedias of the Song Dynasty (960-1279) show them. However, in the succeeding Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368), they become much rarer. Li Zanhua (Li Tsan-hua) carefully painted a closed quiver in his "Tartars Travelling on Horseback"(18) with a finely shaped mouth and an elegantly lined lid opened to show arrow heads that reached to within a handsbreadth of the top of the quiver. Being a Khitan prince who fled to the court of the Later Tang Dynasty, he had probably seen many quivers at first hand. This quiver hangs almost vertically (about 80 degrees) and appears to be suspended from a rope girdle worn under an elaborate belt. Another of his paintings shows an archer and his horse(19). The horse's gear is shown in detail, but the tiger skin and boar's hair decorated quiver stands out. While he checks the balance of an arrow, the archer has slung his bow over his forearm. This is a rare case where the fletching of an arrow from a closed quiver is clearly depicted. The feathers are high and long, but not nearly so long as those on arrows from China in the nineteenth century. This quiver is very narrow, despite its startling boar's hair coiffure, so getting the arrow back in the quiver might not be that easy. There is a Five Dynasties Period fresco, which may explain this by showing an attendant holding an official's weapons including a lacquered quiver full of arrows(20). The arrows seem to be in a patterned silk bag, which might be the answer to the question on how to quickly fill one of these quivers. An anonymous painter of the same period shows another closed quiver from a different angle betraying its rectangular cross-section at the base that gradually changes to a "D" section by the time the top of the quiver is reached.

Byzantine art does show closed quivers occasionally and the influence of steppe cultures can be seen in some details. The icon of Saints Serge and Bacche from Mount Sinai(21) shows a closed quiver with the base of the mouth with a central cusp. A reinforcing rib divides the outside face of the quiver and plain panels decorate the quiver on either side of the rib. The heads of at least three different types of arrows can be identified and a handsbreadth of their shafts can be seen in the mouth of the quiver. No lid is visible and the curves and cusp of the mouth of the quiver make it unlikely that a hinged one could have been fitted.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDS

Two main regions, Hungary in the west and Tuva far north of China in southern Siberia, bracket the vast area over which tombs have yielded remains of closed quivers. Occasionally, the suggestive remains of arrow heads near the waist of the body, with tips pointing in the same direction as the head, are all that indicate a closed quiver. In other cases, metal fittings, traces of bone and the shadow of more perishable parts depict the plan of the quiver.

This Journal in a past article by Dr. Fabian(22) has had diagrams of the reconstruction of a Hungarian closed quiver, which was fitted with metal straps to stiffen the body and metal loops to take the suspension straps. Metal fittings also secured the base of the quiver and the angled cap of the lid.

Even some birch bark bodies of quivers have survived including stiffening rods and decorations(23) from ancient Turkish tombs in Mongun-Taïga in Tuva in Northern Central Asia. The reconstruction by Savin and Semenov has great similarities with the quiver carved in stone at the tomb of the Chinese Emperor, Tang Taizong. However, the reconstruction has no hinged lid and the convex surface of the base of the mouth of the quiver would have made one hinged at its base very difficult to fit. Split canes were stitched through the birch bark sides to give rigidity to this quiver and this feature is common with the Tang quiver. There is even a central rib on the outside face.

Actual examples of closed quivers are on display in some museums that have survived fashion changes and the fragility of their materials(24). The lacquered-leather quiver at Leeds shows interesting details of a type of closed quiver that would have left no archaeological remains under most circumstances. The original shape of its mouth has possibly been distorted by storage, but the shape of the mouth is one of the most variable features of these quivers.

THE DESIGN OF THE CLOSED QUIVER

The purpose of the closed quiver seems obvious. By having the arrows totally enclosed, they were protected from the elements. A rigid body for the quiver provides further protection from being damaged for the arrows. When the arrows are drawn from the quiver, the feathers are unlikely to become ruffled as they could be in a full length quiver of the Sassanian type. The low position of the quiver, rarely above the waist line, keeps it out of the way of an active horseman. From the evidence of many illustrations, it appears that elegant designs added to the military or sporting effect at court.

How these quivers were designed is lost in the mists of time. The makers of such ancillaries to archery have left no books. However, some things can be deduced from the various forms of these items. One thing easily observed is that there are different sizes. Some quivers from both Eastern and Western illustrations are large and commodious, easily able to hold the sixty arrows that Marco Polo claims were the normal complement of a Mongol trooper. Others found in Turkish graves only held a few arrows. These may have been either for a ceremonial or for some other special purpose.

A particular instance of this is found where the quiver holds a dozen of so broad heads with small whistling heads mounted behind them(25). These arrows are of a class that appears at least as early as the first century A.D. amoung the Xiongnu in Mongolia(26) and continued in use until the Qing dynasty in China. There is a painting of the Qianlong emperor hunting hares from horseback with this type of head clearly delineated. Although some of the early heads were trilobate and the later ones were probably two bladed, the association of a large broad head and a sound making device is surely peculiar enough to be remarked upon. Why hares should be hunted this way, I do not know. The use of whistling arrows to scare ducks down onto water to be shot with other arrows has been documented(27). Perhaps the hares' famous curiosity is piqued by the strange noise and they stay in position for a few fatal seconds or maybe the first shot makes them freeze and then the subsequent shots dispatch them. The ancient archers may have combined two arrow uses in one.

This one example might explain why a particular quiver had certain arrows in it, but the Tang wall paintings clearly show that wearing sword, bow case and quiver was an accepted part of dress at official receptions. Whether these were military reviews, where a soldier's equipment was examined, or the accoutrements of a certain office, is not always discernable at this distance in time.

There are problems with closed quivers, as I know from personal experience. Arrows left in them for extended periods have their fletching attacked by feather mites, which happily reduce arrows to bare shafts if left untreated.

The design of the mouth and closure are critical also to the utility of the quiver. If the opening is too narrow, withdrawing the arrows is difficult. If the top of the mouth of the quiver does not have some kind of overhang ledge, the arrows might pierce the archer's palm when he reached for them. The shape of the opening can also have a purpose. In many of the Chinese paintings and in some excavated quivers, the mouth is wider at the bottom and develops two inwards pointed wings towards the top. This made it easy to reach into the side of the quiver and grasp an arrow below the head, but at the same time the shape prevented the fingers from being cut by the edges of broad heads because they were covered. The Altai and Hungary have both yielded quivers of this type. Chinese paintings of mounted barbarians in the North also show these features. Although the Chinese examples sometimes have the wings facing out after narrowing the top of the side opening, this is more than likely a development of the other form.

Various other features distinguish the openings of some quivers from others. Some have a cusp at the base of the opening. This is apparent in some archaeological examples and in a Byzantine icon at Mount Sinai. The cusp precludes the use of any conventional door-like closure with a hinge at the base. On the Hungarian example in Savin and Semenov, the shape of the opening also excludes a side opening door because it possesses the abovementioned wings. Probably a simple waterproofed felt or leather cover was secured over the opening in bad weather. A Chinese drawing of the Song dynasty shows that these were known for open quivers(28). Examples of complete quiver covers of leather survive from the seventeenth century and are illustrated by the catalogue of the Karlsruhe Landesmuseum collection. There is a painting from Ming China showing silk scarves tied over the openings of closed quivers, but it is unclear whether there was a rigid door underneath.

The closed quiver is not well suited for a running man because it will get tangled in the legs and make a lot of noise. When archers are shown on foot, the angle of the quiver to the ground is shallower in some miniature paintings, indicating the adjustable straps have been used to suspend it more horizontally.

Inserting one or two arrows into a nearly filled quiver can damage the fletchings. The whole problem of filling these quivers with arrows at first seems difficult until seeing the painting mentioned above showing most of the length of the arrows in one quiver enclosed in a cloth bag.

Some of these problems have been addressed by early quiver makers. Even the mite problem may be much less when the arrows are in daily use and there probably were various remedies, herbal and otherwise resorted to by archers.

Whereas a big man's quiver might still be useful to a small man, I wonder if the reverse would be true taking into account the hand size / quiver opening dilemma. Some paintings show gaps between the tops of the arrowheads and the upper edge of the mouths of the quivers, which would accommodate longer arrows without much trouble. Detailed measurements and some reconstructions to test this will answer the question. There are instances of a closed quiver being illustrated showing a completely open top, but this is rare and the side opening is very long. Since there are no arrows shown in the illustrations I have examined, I cannot make an argument based on the length of the arrows, but I think they would not come as high in the quiver as in the more common types. These quivers did possess narrowed openings on the side, which would force the archer to grasp the arrows below the heads.

One side effect of having the opening narrowing to the top, to prevent accidental injury from the broad heads, is that the quiver and arrow length must match very closely. In the circumstances, broad heads in the quiver would have to be the possessions of the archer and not something issued him by the commissariat. Armour-piercing arrows, like bodkins, would not have this problem. They would only threaten the archer's hand when it descended on them from above.

This whole problem of hurting the hand, while withdrawing an arrow from a quiver, may seem something that can be overcome with training and practice, but in reality the adrenalin generated by hunting and war make people less attentive sometimes rather than more careful. Anything that removes the chance of injury would have been looked upon favourably.

One thing that really stands out to a modern archer is the way that an arrow is drawn from the quiver. The arrow is gripped just below the head and lifted out of the quiver with a forward movement of the hand. The arrow head is then brought to the grip of the bow and held there by the bow hand while the drawing hand runs along the shaft until it reaches the nock. The shaft is slid forward until the nock passes the bowstring and is drawn back onto it.

While taking a long time to describe, the action is very quick to perform both on foot and on horseback. The quiver hangs low enough on the belt to be convenient when it is need, but out of the way of most upper body movements. In hunting the drawing of the arrow could be concealed by the neck of the horse or the body of the archer so as not to alert the prey. In those techniques where the bow is raised above the level of the shoulders preparatory to being drawn, transferring the arrow to the bow in this way would be easily accomplished. This is the opposite set of movements to the tactic described next. In the context of a different quiver, a similar intent is shown in the famous miniature attributed to Bihzad, where King Dara comes upon his own herdsman and mistakes him for a thief. The king in the foreground is stealthily drawing his bow, which he has concealed upside down on the offside of his horse's neck. Because he is using an open quiver the whole of the action can be concealed.

The shape of the quiver and the fact that the feathers of the arrows were in contact inside it reduced the movement of the arrows when the archer was in violent motion. The Tang wall paintings show the quiver belts were let out a few notches when on horseback, letting them hang more vertically. The same types of quivers are shown at an angle of 45 degrees when worn on foot. Often the upper suspension strap is invisible to the viewer, which suggests that it was concealed by the upper end of the quiver. Some smaller metal fittings found in archaeological digs may be the remains of the upper suspension of these quivers. A horizontally mounted metal loop could be behind the heads of quivers of this type in paintings. Perhaps archaeologists have discovered quivers with these fittings in place behind the arrowheads and perpendicular to them, but I have not found any mention of this yet.

CONCLUSION

While art and archaeology show where the closed quiver was known, neither has yet answered the question of its origin. It was distributed across the Eurasian steppe from Siberia to Hungary and it appeared wherever Turkish influenced nomads had power among the settled people in the littoral states to the south and west of the plains.

To the question, what is the significance of the closed quiver, I cannot give a simple answer. The practical significance relates to utility and can only be judged by how well it fulfilled it function. It is a little late to ask the original users, but making and using replicas can give us some idea.

The historical significance of the closed quiver is seen in the way in which it swept across Asia to Europe. Carried by the Magyars and used by the Byzantines, it penetrated Central and Southern Europe. Strangely, the closed quiver is absent from such paintings as "Khubilai Khan Hunting" in Yuan China, but relatively common in Iran of the same period. This might reflect the tribal mixture of the Mongol armies in Iran, or be the result of different organisational structure at the opposite ends of the empire. One can certainly associate the closed quiver with the Turks, particularly in their nomadic phases, because it appears wherever they have left traditional burials.

The closed quiver was originally a nomad's particular accessory, which through their military prestige became associated with power and maybe even fashion among their settled and more sophisticated neighbours in China, Iran and South Eastern Europe.

It is possible that its most Westerly influence may be seen in the mediaeval crossbowman's quiver. Experts in the field may see similarities in the way the quarrels were carried and the nature of the opening. This could be an interesting field for research.

This is not meant to be an extensive list of the representations and survivals of this ancient form of quiver, but there are many references to the various works of art and archaeology that encompass this subject. In some areas, this study is noticably deficient, particularly in Byzantine and Western European depictions of closed quivers. However, I hope that others will be inspired by this article, in the same way I was inspired by the articles of Dr. Fabian and Doug Elmy. I must also thank Edward McEwan for the notes he forwarded to me and Stephen Selby for the insights he shared with me on the Chinese literature on this subject.

1. The longer arrows may have been developed to carry bigger heavier arrowheads. The longer draws would have provided a more efficient way of propelling them.

2. Georgina Herrmann, 1977, THE IRANIAN REVIVAL, Elsevier-Phaidon, Oxford, page 36, drawing, Capital decorated with a bowcase with a triple-fluted quiver. The arrows are not visible, but the bow shown. The Parthians ruled in Iran from about 200 BC to 224 AD.

3. Edited by Johannes Kalter and Margareta Pavaloi, 1997, HEIRS TO THE SILK ROAD UZBEKISTAN, Thames and Hudson, pp. 37 figures 41-42, show large 'gorytoi' with long eared bows which were worn on the right. The Scythians are usually depicted with the gorytus on the left side of the body.

4. There is yet a third type of quiver, very much looking like the open quiver, but distinguished from it by its history and by the way in which arrows must be withdrawn from it. This is the ebira of Japan and its Chinese ancestor. It even has a closed form, the utsubo, which has a detachable door on its side. The characteristics of this type of quiver are that the arrow points are separated into rows internally, that the arrows are withdrawn by being lifted over a shelf and pulled down and forward, and that the arrows are tied loosely together somewhere between a third and half way up the shafts in the ebira. Undoubtedly, the Japanese were aware of the quivers on the continent, but they followed their own way in developing a new quiver from a combination of their unique open quivers and the concept of the closed quiver. See D. Elmy, 1982, JAPANESE QUIVERS, Vol. 25, Journal of the Society of Archer-Antiquaries, pp. 7-9.

5. Transparent pieces of fine parchment were used to trace a figure and then the outlines were pricked through with a fine needle. Powdered charcoal was then rubbed on the surface of the pounce and a faint, detailed outline was transferred to the new drawing. The figure was then painted in by the artist. Collections of such pounces and sketches were handed down from master to student.

6. J. M. Rogers (Translator and Editior), Filiz Çagman and Zeren Tanindi (Turkish Original), 1986, THE TOPKAPI SARAY MUSEUM THE ALBUMS AND ILLUSTRATED MANUSCRIPTS, Little, Brown and Company, Boston, page 119 and plate 80. Scroll fragments, Akkoyunlu 1450-1500. This piece of silk has detailed paintings of closed quivers resembling Chinese illustrations from encylopaedias. This painting is believed to come from Tabriz by the authors. The figures wearing the quivers are equipped with bows and archers' rings.

7. Albert von Le Coq, 1928, BURIED TREASURES OF CHINESE TURKESTAN, Oxford University Press (Originally by George Allen & Unwin), page 138 and Plate 44, 'The Distribution of Relics', Kyzyl shows armoured horsemen without stirrups, but with closed quivers and tubular bowcases from the second (?) century AD

8. See 1974, MURALS FROM THE HAN TO THE TANG DYNASTY, Foreign Languages Press, Peking, fig. 68.

9. See Bradley Smith and Wan-go Weng, 1973, CHINA A HISTORY IN ART, Gemini Smith, London, page 116, for a large clear photograph of the relief of Li Shihmin's general and charger. All six stone portaits of horses are shown in Ann Paludan, 1991, THE CHINESE SPIRIT ROAD, Yale University Press, pp. 92,94-95, Ill. 109-114. 'Six Steeds' from the tomb of Tang Taizong at Zhaoling. The bas-reliefs are probably based on paintings by Yan Liben.

10. See MURALS FROM THE HAN TO THE TANG DYNASTY, fig. 74.

11. See Georgina Herrmann, 1977, THE IRANIAN REVIVAL, Elsevier-Phaidon, Oxford, page 135, for two views of this enormous carving.

12. See Richard Ettinghausen, 1997, ARAB PAINTING, MacMillan (Albert Skira SA, Geneva), page 37, 'Musicians and Hunting Cavalier', c. 730 AD, a floor fresco from Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbî (Syria).

13. See Aleksandr Belenitsky, 1968, CENTRAL ASIA, Nagel Publishers, Geneva Paris and Munich, Ill. 137: wall painting, Pendzhikent 7th century, archers with closed quivers and unstrung-bow cases holding two bows.

14. See David Talbot Rice and Basil Gray, 1976, THE ILLUSTRATIONS TO THE 'WORLD HISTORY' OF RASHID AL-DIN, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 46, 114, 118, 121, 124, 134, 136, 140, 144, 146, 150, 152, 156, 158 where there are large number of illustrations of closed quivers, two from behind, two with possible side hinged lids.

15. See Robert Elgood (Editor), 1979, ISLAMIC ARMS AND ARMOUR, London Scolar Press, pp. 42, 44, Fig. 44, 47, for the 1370-1380 Shah-Nameh from Tabriz: Hazine 2153, fol. 22b and fol. 102a in the chapter, "Oriental Armour of the Near and Middle East" by Michael Gorelik.

16. See THE TOPKAPI SARAY MUSEUM THE ALBUMS AND ILLUSTRATED MANUSCRIPTS above.

17. See Tamara Talbot Rice, 1965, ANCIENT ARTS OF CENTRAL ASIA, Thames and Hudson, Ill. 249: relief from above window of mosque in Kubachi, eleventh century, of a mounted archer with closed quiver and Ill. 251: relief on slab of three scenes, closed quiver and strung-bow cases on round shield and mounted archer with closed quiver.

18. See John Hay, 1974, MASTERPIECES OF CHINESE ART, Phaidon Press, Fig. 32 and page 12.

19. Edited by Li Lin-ts'an and She Ch'eng, 1971, MASTERPIECES OF CHINESE ALBUM PAINTING IN THE NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan, Page 121 and plate 4. Archer and Horse by Li Ts'an-hua (907-960).

20. Cheng Dong and Zhong Shao-yi, 1990, ANCIENT CHINESE WEAPONS - A COLLECTION OF PICTURES, The Chinese People's Liberation Army Publishing House, fig. 8-26.

21. 1966, THE ANCIENT ART OF WARFARE, Vol. I, Barrie and Rockliff The Cresset Press, Ill. 163, the icon of Saints Serge and Bacche from Mount Sinai.

22. See Dr G. Fabian, 1970, THE HUNGARIAN COMPOSITE, Vol. 13, Journal of the Society of Archer-Antiquaries, Society of Archer-Antiquaries, pp. 13-16 fig. 5, for details of Hungarian archery and the closed quiver. There is a bone cover plate and quiver mouth with seven arrow heads inside from Magyarhomorog, Bihar County illustrated in Istvan Dienes, 1972, THE HUNGARIANS CROSS THE CARPATHIANS, Corvina, Budapest, pp. 38, 88, plate 20, Mouth of quiver . In Hungarian, there is a discussion of archaelogical finds of closed quivers and their reconstruction with diagrams in Dr. CS. Sebestyan Károly, A MAGYAROK IJJA ÉS NYILA, which was lent to me by Doug Elmy.

23. I viewed the remains of birch bark quiver at an exhibition, "The Secrets of Siberia", in Sydney, Australia. However, I was not able to tell whether it was the lower half of a closed quiver or ninety percent of an open one. I was told that it was seventh or eighth century AD. It did display incised lines in a pattern similar to that of the quivers in "The World History" of Rashid Al-Din and the Hazine 2153 manuscript in Istanbul.

24. See the catalogue of the Royal Armouries Museum at Leeds, where one is worn by a mannequin in lamellar armour.

25. A. M. Savin and A. I. Semenov, 1958, KOLCHAN DREVNETYURKSKOGO VREMENI IZ MONGUN-TAÏGA, unpublished notes lent by Edward McEwen. This is a study of the construction of closed quiver from Mongun-Taiga near Tuva. Broadheads with whistling heads are shown in the reconstruction.

26. Edited by Vladimir N. Basilov, translated by Mary Fleming Zirin, 1989, NOMADS OF EURASIA, Natural History Museum Foundation, page 46-47. Hunnic (Xiongnu) arrow fragments with broadheads and whistling heads from Kokel' in Tuva.

27. Ragnar Insulander, 1997, WHISTLING AND BOUNCING ARROWS, Vol. 40, The Journal of the Society of Archer-Antiquaries, The Society of Archer-Antiquaries, 10-12.

28. 1973, MASTERPIECES OF FIGURE PAINTING IN THE NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM, National Palace Museum, Taipei, fig. 13. General Kuo Tzu-i Making Peace with the Uighurs: Li Kung-lin (1049-1106).

Last updated on 19 April, 2001