Follow-up Discussion of the 'Khotan Bow'

What would be

the mechanical advantage, if any, of non-lift off siyahs?

Posted by:

Dale Yessak 07/18/2002, 11:01:20

As I posted in

a separate question concerning the Magyar bow design, what would be the

mechanical advantage, if any, of non-lift off siyahs? I can see that these are

essentially siyahs that are braced so as to have already pre-loaded when braced

to beyond the lift off stage, i.e. leverage optimized while at brace height,

yet such an arrangement would seem to be less efficient than siyahs of a

greater angle that provide an actual "camming" action at lift off. In

the Kotan bow design, we can see that the long, thin siyahs needed additional

bone reinforcement -- perhaps as lateral stiffeners? -- so would this indicate

that the design NEEDED to be non-lift off so as to make it more laterally

stable?

A separate

issue might be the question of whether or not this design petered out as a

technological dead end because the benefits of such a complex design did not

justify the additional work needed when compared to simpler composite designs.

Posted by: Adam Karpowicz 07/19/2002, 06:57:40

Good to see

you here, Dale. You are right in saying the long siyahs would lead to the

"high-braced" bow and non-contact siyahs. From my experience it is

difficult to make a bow with angled, contact siyahs and at the same time to

keep the siyahs long. Such bows are prone to twist and string shedding even at

brace, due the leverages involved. Note, other designs with long siyahs, such

as some Indian for example, have the angle between string and siyahs very small

at brace, no more than some 15-20deg. Bows with angled siyahs, such as Turkish

or Tatar have the siyahs short to minimize this leverage and stabilize the

bows. Angled bows with longer siyahs, such as Manchu or Mongolian rely on

overall stiffness to stabilize - this translates to more massive knees and

siyahs.

The Khotan bow

with the relatively slender and long siyahs required wide bending sections of

limbs for stability plus it was braced high for non-contact. The longer and

lighter the siyahs and the shorter the bending limb, the more efficient the bow

will be, so the Khotan bow would not be a "dead end" as you suggest.

The width of the limbs could be less, I believe, with no loss of stability, on

the other hand such a wide limb distributes the stresses over more material,

making the limbs less likely to creep (string follow) and allowing the bow to

be strung for longer time with little loss of performance, definitely an

advantage.

Posted by:

Dale Yessak 07/19/2002, 09:19:34

I understand

the mechanics (wide limb advantages, etc.), but I'm just curious why this

design does not seem to appear elsewhere. It seems like it would be much more

efficient and a lot quicker than what we term "conventional"

composite designs. Yet it seems as though this particular bow design is a

rarity among horn bows. Why would that be?

I wonder if the Khotan design really was a rarity?

Posted by:

Stephen Selby 07/19/2002, 22:37:42

I wonder if

the Khotan design really was a rarity? The period of the Khotan bow was around

300 AD. All the bows I have seen preserved from that time (four in number), as

well as the 'Gansu' bow which came from another region, was of that design.

Looking back at my translation of the 'Rites of Zhou' about making horn bows

(which may pre-date the Khotan bow by 500 years), there is a lot of stress

placed on limiting the amount of horn used to the minimum required to achieve

the effect.

Seeing Asian

bows of that age from anywhere is unusual; and nearly all the depictions I have

seen of these bows in art take a sideways view onto the bow, so you can't

really guess how wide the limbs were. I have seen just one Tang bow (around

800AD), and that did indeed have much narrower limbs.

Posted by:

Adam Karpowicz 07/19/2002, 12:02:36

As to the bow:

I think the Khotan bow was not perhaps so common, because it requires too much

work to make. The wide limbs complicate the construction considerably, core is

made of many pieces, also horn, not to forget about the bone overlays.

I think the

extreme width of limbs is an exaggeration, unless the bowyer did not have good

horn and wood to use.

Posted by:

Stephen Selby 07/18/2002, 21:34:43

The only

significant difference (at least in surface appearance) between the Khotan bows

and other bows that I have examined used up until the end of the Yuan Dynasty

(to 1368) was (a) that the very wide limbs were later reduced to a size that,

to us now, would seem more conventional, and (b) the siyahs became more

massive.

Posted by: Bede Dwyer 07/18/2002, 20:43:29

I don't think

you can say a design "petered out" if is was the dominant style for

at least 1200 years. The development of thin, stiff siyahs obviously offered

some advantages that prevented the reappearance of recurves for a long time.

I have spoken

to some bowyers who have made this type of bow, though not so extreme as this

one, and they were all very happy with the performance. I think Tim Baker's

comments about stability and economy of materials are right on the mark.

Posted by:

Dale Yessak 07/19/2002, 09:44:57

Bede, it just

seems to me that if the wide-limb-thin-siyah concept had a significant

advantage that it would be seen in many more forms and in many more locations.

But my primary area of inquiry is the siyah angle of bows like this one and the

various Magyar-Hun-Avar reconstructions ... what performance advantage, if any,

would such low angle siyahs provide? Adam has stated that these might be more

stable as opposed to siyahs with TOO MUCH angle due to the latter's propensity

to twist. Perhaps any loss of performance due to a lesser string angle is

offset by the thinner tip's lighter weight. I don't know, it makes one wonder.

The main

reason I'm curious about this is because I made an osage-sinew recurve a few

months ago which I had problems with getting the string to track properly. As a

last resort, I added Asiatic style string bridges along with longer loops on

the string, and the bow became not only more stable, but also faster. I

realized that the speed increase was due to the string bridges effectively

increasing the amount of "string contact" with the limbs and also

because the bow, being braced about an inch lower, gained a little more power

stroke. But the whole experience got me curious about the mechanics of

recurve/siyah angle and the effect it has on the performance of a bow. The

Khotan and Magyar bows are examples of non-contact siyahs, and so my curiosity

was piqued to see if anyone knew if these bows actually represented less, more,

or equal performance advantages over other designs.

Posted by:

Bede Dwyer 07/20/2002, 23:26:34

You wrote

"it just seems to me that if the wide-limb-thin-siyah concept had a

significant advantage that it would be seen in many more forms and in many more

locations" which is pretty much what happened. Due to the use of bone and

antler laths for strengthening the siyahs, quite a few sets of these fittings

have been found in archaeological contexts from China to Roman Britain.

The ratio of

bending limb length to siyah length varies over time and space. The Roman laths

are very similar in size (some quite long pieces have survived in Europe and

China that can be compared). However, over time, siyahs became shorter and

solider. The angle at the base of the siyah changed from almost none in the

Yrzi bow to the pronounced curves in Avar bows from Hungary.

Adam comments

somewhere in this correspondence that the width of the limb was probably

related to availability of suitable timber and lengths of horn. Old Chinese

texts refer to the Northern Barbarians needing several strips of horn to make

their bows because of the lack of horns of suitable length. The

"Traditional Bowyer's Bible" points out how to make good bows out of

inferior timber by making the limbs flatter and broader than usual.

Since the late

1800s, people in the West have been interested in constructing composite bows

and now we have Internet forums like this on the subject. In the past on the

steppe and among its neighbours, bows were important military weapons, but

there was little thought of research and development (Dionysios of Syracuse was

an exception in the West). Detailed testing was not really developed. The ad

hoc testing method was flight shooting which is very old, but that soon turned

into a sport. Target competitions tested the bow and the archer together, but

that also developed into a sport.

Tribal groups

probably each thought their method of bow-making was the best and only changed

when forced to by external forces. In relatively modern times this happened in

Mongolia when it was absorbed into the Qing Empire of China. Mongol Banner

troops were made to use the Manchu bow and eventually stopped making their own.

Modern Mongol bows are a variation of the Manchu bow.

Large empires

like Rome and China could shop around for ideas. The Romans seem to have

adopted the most effective bow in use on their borders. The Chinese were in

such large scale production that military production probably had a life of its

own separate from regional styles.

When a bow

maker today makes a bow, he or she may easily incorporate ideas from different

style of bows. Sometimes I think you start making one type of bow and end up

with another. I don't think any of us knows all the answers so we are still

being surprised. Also I don't think there is a "perfect" bow. Instead

there are bows for different purposes: flight, target, hunting, war, and

practice.

Am I the only

one or is this discussion thread getting too large to keep track of all the

information?

Posted by:

Dale Yessak 07/21/2002, 23:10:46

Point well

taken, Bede. I'm not nearly so familiar as you with the development of

composites, and perhaps I've made an incorrect assumption.

There are

obviously many differing design factors in composites, just as there are in

simpler self and backed bows. I'm just trying to get a feel for them at this

stage.

The Poisson

Effect

Posted by:

Adam Karpowicz 07/12/2002, 08:00:26

Excellent

review of the bow, thanks. It is tempting to make a replica!

As to the

"spoon" shape of limbs, I understand you mean the working sections

cross-sectional shape with the concavity on the back side. This concavity (as I

think wrote to you before at one time) will occur naturally, once a flat-made

limb is flexed.

The

explanation is in the so called "Poisson effect", where the materials

stressed under tension will contract laterally, and stressed under compression

expand laterally (easy to demonstrate with a piece of rubber). This is exactly

what happens in this bow: the back side is under tension, so it contracts, and

the belly is under compression, so it expands. The net effect is the

cross-sectional concavity on the back, as we see.

The wider the

limbs, the more it will show. I made a bow at one time with limbs about 5cm

wide and only 6-7m thick (the proportion of width to thickness not too far from

this bow). The limbs were of course flat when made. Once strung and shot, the

bow acquired this feature immediately, and due to the natural creep in

materials, the limbs stayed like this in the unstrung bow. This distortion of

limbs is permanent.

There is no

doubt in my mind the Niya bow shows the Poisson effect very well.

Posted by:

Stephen Selby 07/12/2002, 08:43:19

That answers

one question, but raises another.

The 'Gansu

bow' is obviously a model. Unless it was once a working bow that was

subsequently stripped of its horn and sinew (which would be a bit bizarre),

then the poisson effect is present in the Gansu bow although that bow has never

actually been stressed in a composite form.

Might a bowyer

anticipate the poisson effect when carving the wooden core?

Posted by:

Adam Karpowicz 07/12/2002, 11:19:20

A strung (not

shot)bow will assume this profile too. The concavity will be more pronounced if

the materials are allowed to creep more, for example in higher humidity and

temperature. The Gansu bow could acquire the profile when left strung in the

grave.

This profile

is not normally noticed at the usual width of bows. Since you mentioned Tim

Baker, I recall having a similar discussion with him not long ago - he had not

been aware of this before. He then found such concavity in a 2" wide

self-bow with the help of a straight edge placed at the back across the limbs.

Posted by:

Pat 07/12/2002, 16:37:37

I have noticed

this effect in reverse while sinewing an Elm bow with pronounced reflex. I

strung the bow backwards and applied sinew. The belly of the bow took on a

concave profile temporarily. I'm sure the moisture from the hide glue aided

this. It was very pronounced. As the sinew matrix dried it no doubt underwent

shrinking across the limb which drew the belly back to a flat profile. After

shooting the limb was basically flat again. The limb was about two inches wide.

Pat

Posted by: Bede Dwyer 07/12/2002, 22:08:33

Thanks for the

explanation of the limb concavity. I have two questions:

Would a model

maker naturally just copy the concavity because that is what all the bows,

which he had seen, possessed? The artificial addition of the concavity in the

Gansu bow could be seen by examining the grain near the uplift, if it is

visible. The concavity on the Gansu bow seems more of a hollowing to me rather

than the lateral flexure apparent in the Khotan bow. Of course, I am relying on

photographs. Stephen is in the best position to check this.

Is the

convexity of the back in many later bows an over-correction for the Khotan

bow's concavity? I wonder if there is a connection, though I admit is very

farfetched at this stage. When you consider how close the Khotan bow is to the

Kum Darya bow and the Hungarian bows on one hand and the Yrzi bow on the other,

we may be looking at a missing link in the evolution of bow design.

Posted by:

Adam Karpowicz 07/13/2002, 06:19:10

It is indeed a

possibility that they copied the profile in wood, although I would very much

doubt it. There can be grain swirls in wood giving an appearance of such work,

proving this would be very difficult.

I do not see

any advantages from the mechanical point of view in the upturned edges of the

bending sections. The edges are under more stress this way. The over-correction

is quite probable, this would be done to compensate, as Pat said, for shrinkage

of sinew as well.

Why the broad

limbs?

Posted by:

Tim Baker 07/13/2002, 18:29:40

Adam, thanks

for the message.

Stephen, Adam:

Yes, level-3 deja-vu. Part of the thinking behind the TBB design was that more

reflex would store more energy, but that conventional-width highly reflexed

bows exceed the elastic limit of materials, take much set, and end up with less

efficient just-unbraced profiles, the solution being more horn-sinew to

properly hold that extra energy, and that this horn-sinew would have to be

added in width not length or thickness. The idea was that if thin/wide enough

the limb could hold a more than tips-touching just-unbraced reflex. But I

wonder if the Khotan bow was highly reflexed. It appears not to have had

string-liftoff siyah action, a low energy storage design. So possibly the wide

limb solved the problem of normal energy storage in low-elasticity materials—most

likely belly material. On the other hand, a no lift-off design would be more

stable, quite a valuable feature in the field, and if reflexed as per above,

stored energy could be very high, and stack still low. Of course there are

other possible explanation for the wide limbs. As for the back’s concavity: if

the limb was originally rectangular, which such wide limb must largely be, then

some portion of the spooning must be P-effect. Adam made me aware of this a few

years ago, and the most simple of tests demonstrate it exists on all near

rectangular limbs. But I imagine that most of the spooning here is due to sinew

contraction. I think the P effect can be overcome by appropriately convexing

the limb during construction, and/or possibly by inhibiting the effect with

bands of sinew running across the belly. Both ideas I believe Adam introduced

on another bow site. But even without such correction ultra-wide limbs work

well and safely--Pyramid shaped limbs four feet wide [plywood] for example.

I sure would

like to see someone make a more than tips-touching-when-just-unbraced composite

as per TBBlll, possible needing four or so inch wide limbs. I think it could be

the fastest natural-materials bow ever made.

Please set me

straight on any incorrect assumption or conclusion I might have made here.

Posted by:

Stephen Selby 07/19/2002, 22:42:02

Following up

on the comments made about the Khotan bow design reducing string-follow: at

Khotan, the maximum temperature range over a whole year would be -20 to +40

Degrees Celsius.

Posted by: Pat 07/13/2002, 22:34:38

If the bow

tended to hollow towards the back due to the P effect would the linear joints

in the horn strips not be prone to separating? Perhaps this would be more of a

problem if the limbs were severely reflexed. It is interesting that bows with

multiple horn strips do seem to exhibit a net reflex(handle setback and Siyah

angle) but the working section of the limb may have(deliberate?) "string

follow". This bow and the Persian bows in a past letter and Volume 2 of

TTBB being notable examples. Any thoughts if this may be the reason for the

lack of reflex in the working limb? I also wonder if the low reflex in the

siyah (likely no lift-off during draw depending on brace height) may be because

a very wide flat limb is quite prone to twisting. A highly reflexed siyah might

make the limb very unstable. I know the reflexed wood/sinew bows I have made

with a thin wide limb and siyahs are very "wobbly" (although I'm sure

horn added would make for a more stable limb). Still, wide and thin in any

material usually means it can be twisted and warped very easily. The bow shown

looks like it would be quite stable due to subtle modifications.

Posted by:

Adam Karpowicz 07/14/2002, 06:27:35

It is true the

horn strips are indeed prone to separating in bows with multiple strips on the

belly. Persian bows of this design were covered with sinew all around to

alleviate this problem. On the other hand, if the bond between the wood and

horn is good, the separations between the horn strips do not affect

performance.

I made only a

couple of bows with the strips so far and I am now sure the strips, as opposed

to solid horn, make the limbs more flexible (at the same thickness), so less

efficient. I also think the Khotan bow is overbuild, narrower limbs would be

much better for a bow this length, given the resiliency of sinew/horn

combination.

I believe the

deflex in the limbs is not deliberate in the Khotan bow. The limbs had to be

build in full reflex, possibly the bending sections were straight in this case.

The deflex came with use.

From my

observations, the "wobbly" problems with wide and thin limbs happens

only if the bending sections are very long. In this bow, they are relatively

short and I would not expect any such problems here. The short bending sections

plus the non-contact siyahs make the bow very stable.

Limb-to-Siyah

Transition Questions

Posted by:

Bede Dwyer 07/17/2002, 09:48:09

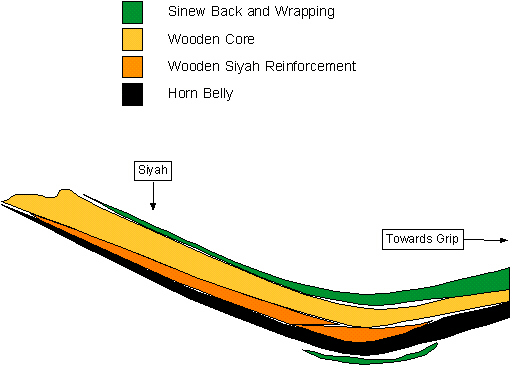

I have

attached a rough sketch made from the x-ray photograph of the siyah. It covers

the area from the small fracture in the core of the siyah to the point after

the siyah has joined the main limb.

I have guessed

that the belly side of the wooden core of the siyah was reinforced with another

wooden strip. I assume that it is broken up and has shrunken due to drying. In

the Qum Darya bow, the horn that covers the belly-side of part of the siyah

appears to be a separate, overlapped piece (but that is based only on a

drawing).

I have some

trouble interpreting the x-ray, but it was of immeasurable help in

understanding the photographs of the siyah. From reading the Traditional

Bowyer's Bible, I know that bows were made in America in the 20th century with

static recurves reinforced on the belly.

Stephen, you

are in the best position to comment on this as you have seen and handled the

bow. What do you think?

Posted by:

Adam Karpowicz 07/18/2002, 06:22:02

Bede, if I

understand you correctly, you believe the wooden reinforcement in the siyah is

in one piece (orange on the drawing). I think the broken belly fragment of the

piece is actually another, short piece of wood, glued onto the belly of the

core at the knee. It would be easier to manufacture, by gluing the first (long)

piece on the siyah, then filing it smooth and gluing the next to build up the

thickness there. Otherwise the bowyer would need to pre-bend a thicker piece of

wood, not an always an easy task, depending on the length etc. It is quite

possible both methods were used as well, maybe even on the same bow.

Posted by:

Bede Dwyer 07/18/2002, 20:36:34

I agree with

you, but I wasn't sure. I coloured the siyah reinforcements orange to

distinguish them from the core. I did not think they were pieces split from the

core by drying out of the wood, but I was not certain whether they were

individual parts because of the degree of break up of the pieces.

Posted by:

Stephen Selby 07/17/2002, 10:38:06

The bow is at

the museum undergoing further tests. This picture is all I have to hand. The

picture is a bit misleading: the darker brown wood has shrunk somewhat. The

extension of the horn in the limb, visible in the X-ray, is not apparent in

this view at all.

ENDS