Perfecting the Mind and the Body

© Stephen Selby, 1999

The Chinese concept of the ‘accomplished archer’ comprised the achievement of a number of goals. These could be summarized as –

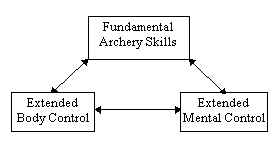

Fundamental skills

The fundamental skills were those practical archery skills described in the works of Wang Ju (Tang) and Li Chengfen (Ming). Both of those authors drew on a structure laid down in previous works – at the most basic level, the core material found in ‘The Archery Ritual’ of Confucius:

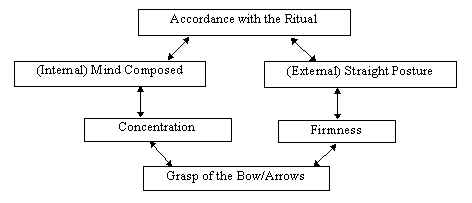

Thus archers were required to meet the requirements of the rituals on entering, leaving or making turning movements in any direction. When their minds were composed and their posture straight they grasped the bow and arrow and concentrated. Only when the archer had grasped the bow and arrow and concentrated was it possible to talk of meeting the requirements of the rituals. This was a means of assessing their virtuous conduct.

The basic core of fundamental skills in ‘The Archery Ritual’ and their relationship to body control and mental control could be expressed as follows –

Mental control

Liezi was a Daoist philosopher of the Han period. This is from his writings:

Liezi put on a show of his archery skills for [his friend] Viscount Hun. Bringing the bow to full draw, [someone] balanced a cup of water on the inside of his elbow and he shot off his arrows so that the arrowheads struck one after the other against the arrow he had loosed off before. Throughout the shooting, Liezi’s stance was as solid as a statue. Viscount Hun said,

"This is just ‘archery shooting’, not ‘non-archery shooting’. Supposing you and I climbed a high mountain, scaled a precipice and faced a yawning chasm, what would your shooting be like then?"

There and then Viscount Hun [took Liezi] straight up a mountain, scaled a precipice, faced a yawning chasm, turned his back out to the chasm so that half of his feet stuck out over the edge and waived to Liezi to come up and join him.

Liezi grovelled on the ground and sweated so much his feet got wet. Viscount Hun said,

"Any man who has attained his skill in full will have an unbending spirit, no matter whether he faces the sky above, plunges into the foaming depths, or journeys to the corners if the earth. But now you are scared out of your wits and there is terror in your eyes. I think you still have some way to go to towards perfecting your archery, don’t you?"

Liezi had perfect archery technique. He could do all the party tricks that were part and parcel of an external display of excellent archery; and yet Viscount Hun was not impressed. The reason was that Liezi did not have the necessary mental control. The route to correct mental control was set out in Confucius’s ‘Great Learning’, and it was elaborated by the Song philosopher Zhu Xi into a contemplative method of self perfection (possibly influenced by Zen techniques of meditation).

Qi Jiguang (1528–1587), the famous Chinese general who fought against the Japanese pirates in the Ming Dynasty, was the first to include an explicit reference to this point in his writings, ‘A New Book of Discipline and Effectiveness’. His reference was undoubtedly influenced by the writing of the philosopher Wang Yangming (1472–1529). Wang Yangming was brilliant scholar who had excelled in the exposition of the neo-Confucian ideas of Zhu Xi, but found them too restrictive and elitist. After gaining an interest in the practice and principles of qigong, Wang Yangming developed a new view on the Confucian classic which dwelt on the correct approach to study and self-refinement, the "Great Learning" and put forward the view that artificial social divisions should be broken down, that self-imposed limitations should be removed, and thus self-perfection was within the grasp of all men.

His view was then taken up and expanded upon at the end of the Ming Dynasty by Li Chengfen , a little-known writer whose ‘Archery Manual’ has been preserved in a Ming Dynasty encyclopedia, the ‘Complete Collection of Ancient and Modern Books and Pictures.’ Li Chengfen was a born in Anhui Province and lived in the latter part of the 16th and start of the 17th century. He deeply respected Qi Jiguang and the Wang Yangming school. He wrote –

Qi Ji-guang said, "The ‘Record of the Rituals’ refers to "Grasping the bow, concentration and firm stance." ‘Concentration’ is minute attention [to your shooting]; ‘firm stance’ refers to maintaining a firm grip on the bow. The word ‘concentration’ is the same as ‘meditation’ found in the ‘Great Learning’: "He meditates on it and then he is able to achieve it." When a Gentleman is seeking to prefect himself completely, he knows at what point he should have reached that [perfect] stage, and resolves to attain it, then becomes tranquil, then at peace. And he must be able to meditate on these qualities before he will be able to totally fulfil his aim. When a Gentleman is practising archery, at the point where he has already drawn his bow fully, and in the moments before he releases the arrow, he must concentrate on his shooting stance, and then he will have the assurance of hitting the target.

Mental control techniques certainly could not be employed before the fundamental skills had been thoroughly learned. Chinese instructors looked down upon self-taught methods. The reason for this will become clear when we study the writings of Gao Ying (Ming) in his ‘Orthodox Introduction to Martial Archery’

A proper, recognized style of archery is like a highway: it has a natural logic to it. Once you get onto it and keep going, in the end you arrive at the main city gate. From there, you can get to City Hall and from there again you can get into the rooms of the Hall. It’s a matter of days before you get where you want. But if you get on the wrong road and keep going, you get to some suburban side-road. It’s like going to the capital and taking the wrong exit: the harder you drive, the further away you get.

The student had to perfect himself in the fundamental skills belonging to a recognized method These skills had to be practiced unceasingly until perfect form was no longer a matter of conscious effort. That is because any resources being used for conscious control of the shot inevitably diminished the resources needed for the ultimate purpose of the shooting.

The ‘Great Learning’ is also a ‘recognized method’. It teaches that the purpose of the study of any subject is to regard study as completed only when the predetermined goal has been attained. This ultimate is perceived in advance as a target, for the student then resolves himself to attain it If he has resolved himself, he is them able to clear his mind of extraneous matters. Once having cleared his mind of extraneous matters, he can be at peace. Once at peace, he is able to meditate. Through meditation, he gets to tell the forest from the trees, tell causes from effects, and to put first things first. This is close to the principle expressed in the ‘Great Learning.’ None of these things involves the learning of basic technique: that must be assumed to have been thoroughly ingrained before this process starts.

If we want to go back and review the enigmatic comment of Viscount Hun to Liezi we should be able to understand it better on the basis of the explanation of the ‘Great Learning’: Liezi’s shooting ‘was shooting, merely according to the principles of archery, not according to the ‘non archery’ concept of perfection.

If you want to understand what it is that the Japanese practitioner of Kyudo or the Korean traditional archer seeks to achieve, it is this concept of holistic perfection expressed in the ‘Great Learning’ stressed by Wang Yangming. That a Japanese practitioner may express the aim in terms of the teaching of Zen makes no difference.

Bodily Control

If mental control can be extended beyond the immediate mental clutter of the requirements of the shot, it is also true that the archer’s control of his body can also be developed beyond the details of the physical performance of the shot. The most important of the methods to achieve this was the control of ‘qi’.

Qi is not magic. On the other hand, it cannot readily be explained in standard western medical terms. For example, qi is understood in Chinese medicine as a force which ‘flows’ like a liquid along a system of channels which western medicine does not recognize. I shall couch my explanation which follows in western terms, notwithstanding that doing so will result in the loss of many nuances.

The term ‘qigong’ can be analyzed as ‘mental control over breathing’. At least, that is where the theory and its study start. In the Warring States Period the writer Guan Zhong (d. 644BC) explained that the mind’s position in the body was the dominant position; the ‘spirit’ was the distillation of ‘qi’, and ‘qi’ was the ‘charge’ of the body. Set out in these terms, the early view of qi was that it was energy, which could be concentrated and this could be achieved through the mind. From the Han Dynasty on, the concentration and movement of qi was one of the major endeavours of traditional medicine.

The Daoist school believed that animals could instinctively marshal their qi to prolong their lives and rid themselves of illness. In particular, the tortoise was considered to achieve extreme age through the fact that its breathing was so slow as to be almost imperceptible. From this developed the idea that the typical movements of animals – the elasticity of the snake’s body, the stretching of a birds’ wings, the belligerent stance of the bear or the undulation of the dragon – could all be mimicked by man to good effect. Added to this, slow, deep breathing would maximise the charge that breathing brought into the body.

From this theory there developed very many styles of exercises, and such exercises became combined with almost every religious persuasion and every branch of Chinese martial arts. The effective mastery of qigong exercise could not be divorced from the practice of mental control as set out in the ‘Great Learning’. In martial arts, the aim of the integration of qigong was firstly to ensure that the demands of natural breathing did not conflict with the moment-to-moment demands of physical movement of the body, and if possible to bring to bear the ‘gathering’ of qi to make one’s fighting more effective.

One technique of qigong is learning to breathe by using both the ribcage and the diaphragm to inflate the lungs. The muscle tension required to keep a heavy bow at full draw inhibits the free movement of the ribcage; so facility in diaphragm breathing is clearly helpful in that it helps ensure that sufficient air comes into the lungs.

Another technique is hyperventilation. Practitioners of qigong interpret the tingling at the ends of the fingers caused by hyperventilation as a sign that the qi has effectively been pushed to the extremities of the body. Hyperventilation before the draw can help ensure a sufficient supply of oxygen to allow the muscles to work without the onset of shaking.

A further aim of qigong is to cause the combination of the meditation technique of the ‘Great Learning’ and bodily control techniques of qigong to bring about a semi-hypnotic effect. This state is very easy to enter, requiring only the combination of any thoroughly familiar set of slow body movements and deep, natural breathing. The resultant mental state can be used to counter the fear of examination, competition or battle. It is claimed – although this is not beyond doubt – that this condition can make an a performer of martial arts or archery achieve feats that would otherwise not be possible.

Finally, qigong once learned is able discipline the body even when only being practiced in the mind. For example, a series of complex actions (such as setting up an archery shot) combined with proper breathing can be rehearsed mentally without any body movement other than that required for breathing. Such repetition will gradually make a right-handed archer able to shoot left-handed or vice-versa. Handedness is in the brain, and it is not unreasonable that mental exercise can overcome it.

Naran Changgiun, a member of the Machu ruling class in the 1640s, wrote a book on archery in which he devoted special thought to this aspect of qigong and archery. Here is a short extract which deals with the relationship between archery and the practice of one piece from a well-known set of Qigong exercises.

A person’s body is imbued with strength through Qi and the point below the diaphragm (dantian) is the place where Qi returns and settles… …A person skilled in the control of Qi will not fritter it away with pursuit of enjoyment, and will not damage it through sadness or anger. His intake of breath is natural and exhalation is measured; then it imbues his whole body and penetrates to his four limbs. When it comes to the point of using Qi in conjunction with shooting, it has penetrated throughout his whole body, all his joints are limber and his strength and proficiency are invigorated within his Qi.

On Practice

Proficiency in martial skills is no exception to the need for a fixed technique. Body technique, arm technique, finger technique, eye technique are all part of the criteria for judging martial skills. The good student does not need to slave incessantly with a bow and arrows, thinking about it day and night without pause. He can practice the actions of holding the bow and nocking the arrow empty-handed, and when he has managed to do it consistently for some time he can go on to the practice the action of releasing just as if he were shooting for real.

In the Qigong practice described in Daoist texts, there is described a method of ‘using both hands as if pulling a heavy bow’ prescribed to cure rheumatism. This is what the method was originally intended for: but applying it to drawing a bow, it has a double benefit. First, pulling without the bow is good exercise for the upper arms and lateral muscles; although you cannot release, you still draw back with the string, and pull back the dorsal muscles. Moreover, the proper technique for your hands must not be neglected. The best thing is to draw without the bow, and after a pause, you perform the action involved in releasing. After a time, you will become accustomed to it and when it comes to real shooting, your skill will come from familiarity.

Qigong does not start and stop with breathing. It encompasses diet, bodily functions and mood. That is the principle underlying the ‘Archer’s Ten Commandments’ in "The Guided Tour through the Forrest of Facts" by the Song author Chen Yuanliang.

Mental control and keeping in proper physical shape

The classical method says: "Set up your shot in your mind, then carry it out with your hands." So if your mental control goes, your shot has no basis for hitting the target. In archery, there are ‘Ten Commandments’:

thou shalt not let your mind wander;

thou shalt not be distracted by worries;

thou shalt not arrive [for your archery session] in a rush;

thou shalt not be drunk;

thou shalt not be hungry;

thou shalt not shoot after overeating;

thou shalt not be angry;

thou shalt not shoot when you don’t want to;

thou shalt not be so engrossed in shooting that you don’t want to stop;

thou shalt not compete aggressively.Don’t plan on taking up archery if you can’t break these bad habits! If you score a hit, don’t be happy otherwise your mind will turn contrary on you. If you miss, don’t be unhappy, otherwise you will lose your concentration and it will be beyond control. Normally, when you grasp the bow and the string and you nock your arrow, you should concentrate naturally on your target, and use the power of your mind to carry the shot. In your daily life, make an extra effort to control your breathing, regulate your intake of food and drink, avoid extremes of temperature, control excesses of joy or anger and restrain your interests and desires. This is very important in archery.

Qigong also contains a strong element of achieving balance. In Chinese traditional psychology, a positive mental condition is built up only gradually yet can flip instantly to its opposite like the yin-yang symbol. That is the principle underlying the statement: "If you score a hit, don’t be happy otherwise your mind will turn contrary on you. If you miss, don’t be unhappy, otherwise you will lose your concentration and it will be beyond control."

The distinctive external features of Chinese archery – the knees bent and the legs spread at the hips, the elbows, shoulders and wrists in a straight line, the belly inflated at full draw – are all symptoms of the archer’s attempt to ‘move his qi’ in the correct way. In his novel ‘A Chance Encounter’ written in about 1820, the author, Li Ruzhen, describes in very accurate detail a girl giving an archery lesson to her friends. (Women did not do archery in China at the turn of the 19th century, but a woman archer was required for the plot of the novel.)

If you don’t get your hips down, then you can’t get your breath down to your diaphragm either and the air pressure will build up at the front of your chest cavity. Then after a bit you’ll start panting and your heart will race and you’ll get a stitch in the front of your chest, too. In the end you finish up with a strain injury.

Straight joints were thought to open the channels required to allow qi to pass freely to the extremities of the body. This is illustrated by ‘The Secret Theory of Outstanding Archery’ by Zhang Cimei written in about 1750.

According to the ‘Theory’, "The qi must run free and the tendons must be stretched", meaning that to get the qi running free you must have the tendons stretched first. To put it another way: once the tendons are stretched the bone cavities will open, the collarbone can be displaced and then power can be delivered in a straight line to the elbows and hands: that is how the qi can run freely.

This is no more than a small representative sample of quotes from the Chinese literature relating to self-improvement through the combination of archery, study-discipline and qigong. It would appear from both the writings of the novelist Li Ruzhen and the Manchu writer Naran Changgiun that archery in conjunction with qigong was regarded as a good preventative for rheumatism. Li Ruzhen’s heroine says: . "All along people have been doing archery for relaxation, to stretch their muscles and joints and improve their circulation. It can keep away chronic illness and increase your appetite. It’s good for people."

I have heard it said that Korean Olympic archers train in traditional skills and then import the traditional skills into Olympic archery using western recurve bows. The disciplines of self-perfection and qigong are certainly among those traditional skills. Although Chinese sportsmen have not yet brought these skills to archery (traditional archery having died out in China), qigong techniques are undoubtedly being brought to bear in other sporting disciplines. It will not be long, I suspect, before they are imported into western sports training as well.

20 February 1999