Extracts from Previous ATARN Newsletters

Index

|

antiquities, archery |

Chinese Stone and Earthenware Archery Figures (Northern Wei, Five Dynasties, Song) |

|

archery, Asian traditional |

A Report on Traditional Archery in Asia n 1959. (Indonesia and Pacific) |

|

archery, Assyrian |

|

|

archery, circus acts, Mongolia |

|

|

archery, Korea |

|

|

archery, Manchu |

|

|

archery, Sapmi |

|

|

archery, Tibetan |

|

|

archery, traditional |

|

|

army |

|

|

arrow-making, Korean |

|

|

arrows, Indo-Persian |

|

|

arrows, Tibetan |

|

|

bow, child’s |

|

|

bow, han |

|

|

bow, Indo-Persian |

|

|

bow, Khotan |

|

|

bow, Khotan |

|

|

bow, Liao |

|

|

bow, pebble |

|

|

bow, pellet |

Pellet-bows |

|

bow, pellet |

|

|

bow, reproductions, Grozer |

|

|

bow, Scythian |

|

|

bow, Sinhalese |

|

|

bow, Song |

|

|

bow, strength |

|

|

bow, Tibetan |

|

|

bow, Turkish |

|

|

bow-making,Chinese |

|

|

bow-making, Korean |

|

|

bracer (arm guard) |

|

|

crossbow, Han |

|

|

crossbow, Han |

|

|

crossbow, mechanism |

|

|

crossbow, Qin |

|

|

crossbow, Warring States |

|

|

crossbow, warring states |

|

|

crossbow, Yunnan |

|

|

dog-shooting |

|

|

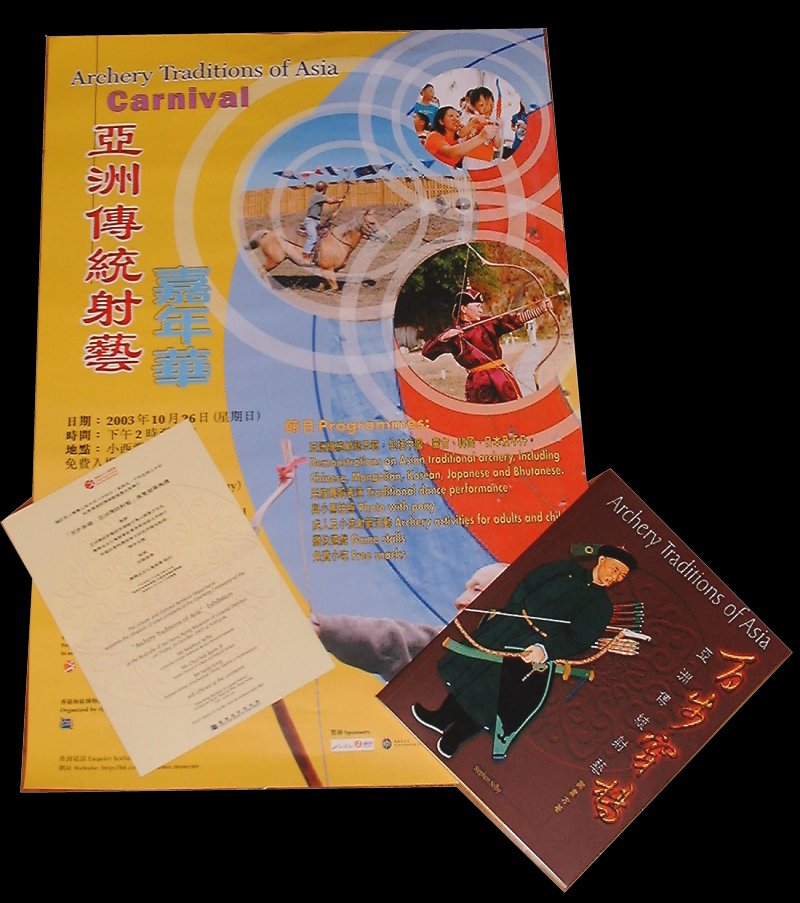

exhibition, museum |

Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence: Asian Archery Exhibition |

|

festival |

|

|

folklore, invention of the bow |

|

|

folklore, Zhang Xian |

|

|

golf |

|

|

grip |

|

|

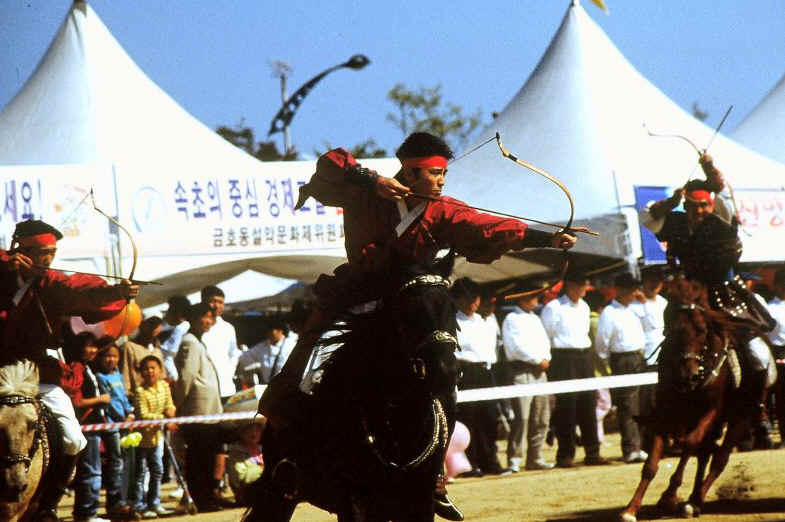

horseback archery |

|

|

horseback archery |

|

|

Ju Huan hao |

|

|

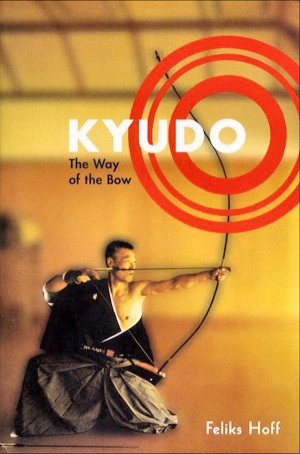

kyudo |

'Kyudo: Die Kunst des japanischen Bogenschießens' .Felix Hoff. (Book Review) |

|

longbow |

|

|

majra |

Korean Side-arrow guide (Arabic and Turkish Majra) |

|

Malaysia |

|

|

materials |

Traditional materials v. Modern Materials for Traditional Archery |

|

museum, Korean |

|

|

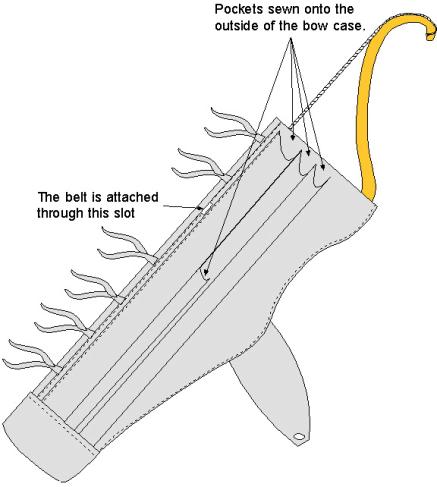

patterns, quiver |

Quiver and Bow Case Patterns by Cherrie Anne Button (1), (2) |

|

Taiwan |

|

|

tepeliks |

|

|

thingies |

|

|

tools |

|

|

training |

|

|

twist |

|

|

writing fiction |

|

|

Xibe Manchus |

|

|

yumi maker |

February 1999

Asian Traditional Archery Grip on the Bow

From Soon See <soons@sharkmm.com>

I read in a book called Arab Archery (which is a translation of a manuscript written in the 15th century) that Arabic bow has its center located at the point which is one finger width below the top of the grip. In other words, one finger width of the grip plus the the top limb plus the top siyah constitute one half of the bow while the remaining grip plus the bottom limb plus the bottom siyah constitute the other half of the bow. This means the top limb is slightly longer the the bottom limb and the top siyah is slightly longer then the bottom siyah.

According to the author (whose identity is unknown) of the manuscript, a bow with this configuration is the best. (I don't remember exactly how he put it) After reading the book, I would assume that the author nocked the arrow perpendicular to the string (not pointing down or pointing up) and the arrow would pass through the point which is one finger width below the top of the grip.

I have not read any articles on Chinese Archery that mention anything about the top limb being slightly longer than the bottom limb and I would like to know if you have.

Stephen Selby

No, I have not seen such comments in Chinese texts. Chinese bows seem always to have been symmetrical, and Chinese regarded assymetrical bows (e.g. Japanese yumi) as an oddity. But a low grip seems to be shown on some early Chinese (e.g. Han) images on archeological remains.

Painting on a Western Han pottery urn. c. 100BC

Copyright Stephen Selby 1998

However, to confuse the situation slighly, the correct grip for shooting the stone-bow always required the bow-hand to be dropped well below centre. Sometimes, it is hard to see on archaeological remains whether a stone-bow or arrow-bow is intended.

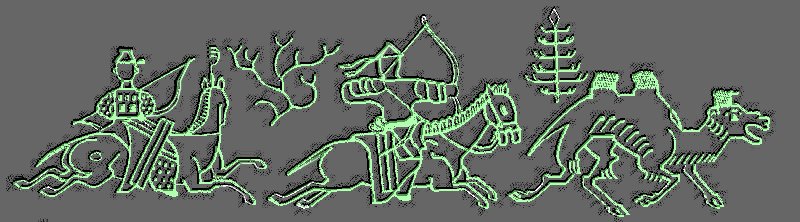

Western Han Tomb brick showing a stonebow archer on horseback

Copyright Stephen Selby 1998

As far as I know, the Chinese bow of the Qing dynasty had both limbs of the same length. Correct. But I cannot be sure that the weights of the upper and lower limbs were equal.

Soon See

I also noticed from some photos (including the one in your articles published in Instinctive Archer)

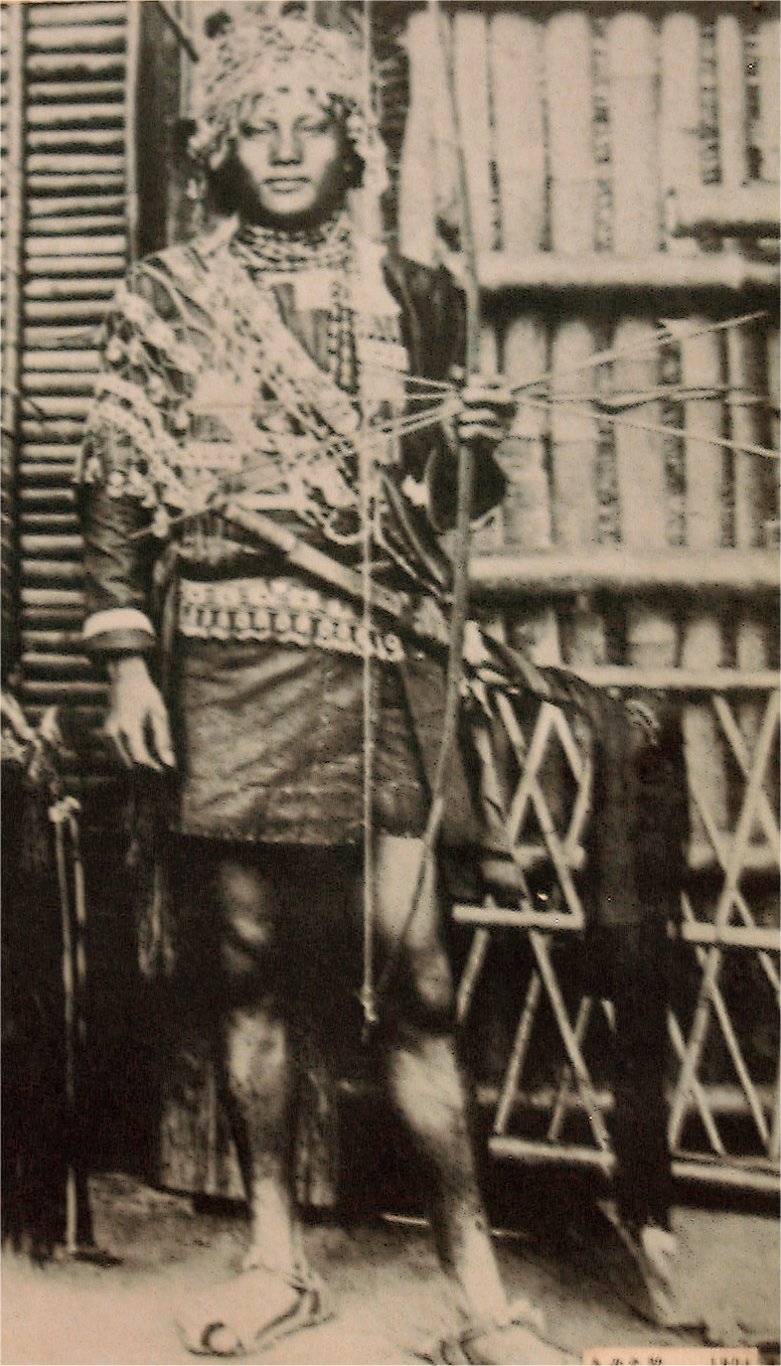

Photograph by John Tomson. c. 1865

Repro. Copyright Stephen Selby 1998

that archers shooting bows of Qing dynasty nocked their arrows at the center of the string which made the arrows point upward. I am curious to know what you think about that and if you have tried that. I have never had good result with nocking at the center of the string which makes the arrow point upward.

Stephen Selby

No. Chinese archery manuals are explicit on the point that arrows may point straight ahead (preferred) or down, but never up. The photograph in my article may not be a helpful example: I suspect the archer was getting tired of holding at full draw for the photograph and started losing his stance!

Soon See

I personally think the best place to nock an arrow is at the center of the string. If both top and bottom limbs are of the same length then the (point of the) arrow would be pointing up (which I never had successful result with, the arrow would slap my hand). If the top limb is slightly longer than the bottom limb then the arrow may be perpendicular to the string. Please let me know what you think and what your experiences were.

Stephen Selby

My understanding of modern recurves is that the upper limb is more powerful than the lower one and therefore the arrow must be nocked above centre to compensate. I do not know the theory behind that. My own Chinese shooting technique is to ensure that the arrow forms an angle at 90 degrees to the string before drawing and that it passes over my thumb slightly higher than the centre of the grip as my bow-hand fingers need to have good contact with the front of the grip.

Tom Duvernay

In regards to Korean bows, the limbs may be of similar/same length, but strength will vary between upper and lower (as will brace height).

Bede Dwyer

I have the material from the Middle East on the asymetricality of bows. It appears in Saracen Archery, where McEwen made a reproduction of the bow and tested it, and in Arab Archery. Arab Archery has descriptions of old Arab wooden bows as well as composites. The bows depicted on Sassanian silver plates generally seem to have a larger upper limb and Latham and Paterson (Saracen Archery) related this to a Central Asian prototype. However, the differences in limb size were small compared to Japanese yumis.

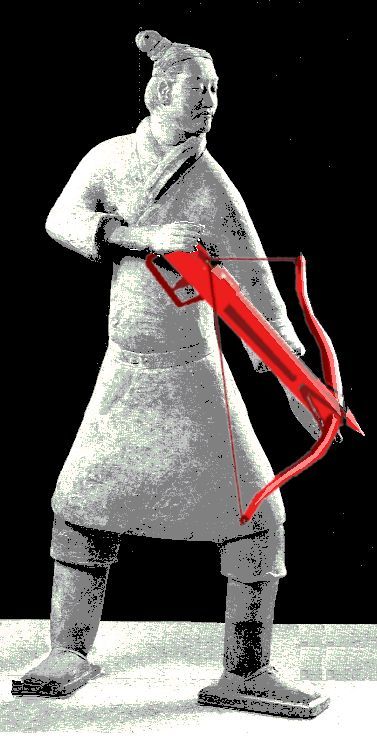

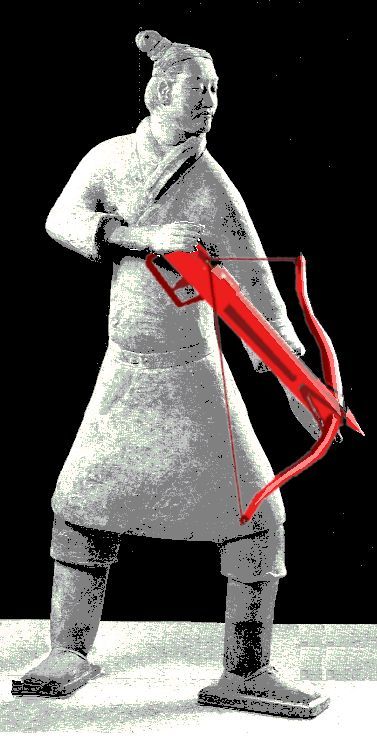

Crossbows in the Qin Shi Huang Tomb

From Bede Dwyer <bededw@tpgi.com.au>

This is the body of a letter I sent to Edward McEwen after buying a

book on Saturday. It is reasonably self-explanatory, except for my comments about the

bowstring. For a number of years I have doubted reconstructions of Chinese crossbows with

two little bars on either limb on the belly side of the bows. I found an excavation report

which identified the shadows in the earth of the excavation as struts to give shape to a

canvas bow-cover. This was clear in the drawings from the site. So the struts existed, but

were not attached to the bow. This was in the excavation of the terracotta warriors.

I would be interested if anyone has turned up any more information on this model crossbow,

particularly how it was reconstructed.

The letter follows:

I have just bought a book with some really interesting photos in it. I do not know if you

have seen it yet , but the title is The Qin Terracotta Army Treasures of

Lintong by Zhang Wenli published by Scala Books and Cultural Relics Publishing House,

1996, reprinted 1998.

Stephen Selby

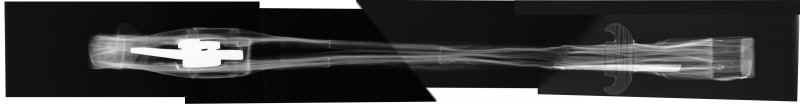

For good photographic reproductions, see 'Bronze Chariots and Horses of Qin Shi Huang's Mausoleum' Ed. Wu Yongqi et al. Tai Da Publishing Company. ISBN 962 7084 64 6. Here is part of a relevant photograph by Guo Youming (copyright), edited and enhanced by Stephen Selby, for private research and study.

Bede Dwyer

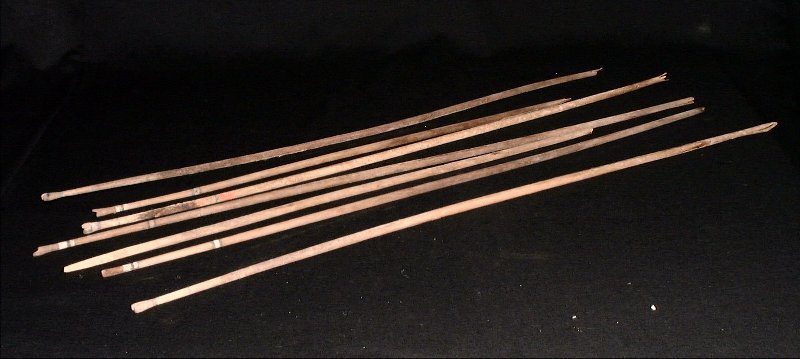

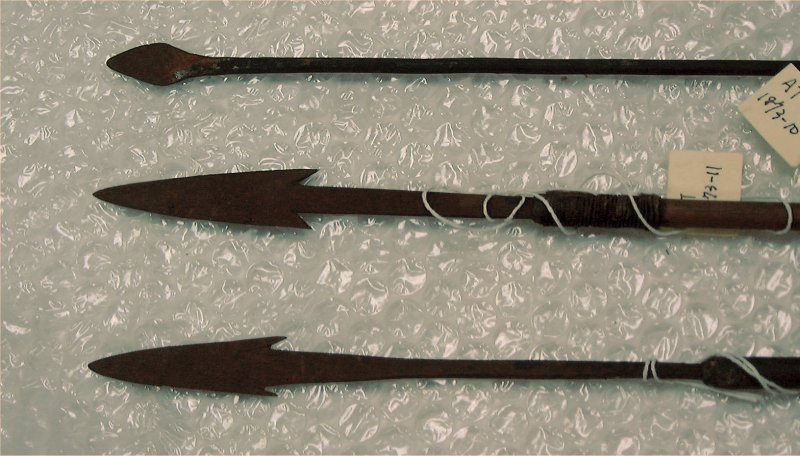

There are a group of colour photographs of the half-size model chariots and horses made of bronze featuring some detailed pictures and a few measurements of the crossbow and arrows that accompanied one of the chariots. The arrows are of two types: blunts and narrow broadheads. The fletching is painted white as are the blunts. The arrows have nocks and are unlike western quarrels. Three imitation feathers are mounted some distance from the nock, probably equi-distant from each other and having the same relation to the nock as western target arrows (i.e. not the "Oriental" style). The shape of the feathers is similar to plain Japanese fletching: rounded leading edge, parallel top and bottom, and trailing rear edge. There was a quiver mounted on the left front corner of the chariot body. There is also a narrow box with a hinged lid and a chain suspension for storing arrows.

The reconstruction of the crossbow is problematical. The major area of

controversy, from my viewpoint, is the string. In the photograph of the chariot as

excavated (a very flat chariot), the bow is detached from the stock and the string is not

visible. The reconstructed (read "put back together") crossbow has a bronze

bridle of cord connecting it to the stock. The hole in the stock for the bridle has a

twisted string run through it tied at either end to points one sixth of the way from the

respective bow tips. This string is a piece of twisted bronze wire and it runs straight

between its end-points. The shooting string is a smooth bronze object with thicker loops

at each end hooked over the tips of the bow. The end loops seem integral as there are no

visible knots. This thicker string runs over and touches the top of the stock. The stock

has a decorated lock and butt-cap with a substantial trigger guard. The stock has a

profile similar to later Han crossbow stock, with the exception of its pistol grip, which

is an unadorned vertical cylinder dropping from the stock to the rear of the trigger

guard.

The measurements are as follows:

bow 70.2 cm

bowstring 66 cm

stock 39. 2 cm

blunt arrow 35.4 cm

broadhead arrow 35.2 cm

blunt 2.2 cm

arrow box 38 cm (l) x 5.4 cm (w) x 11.8 cm (h)

When the dimensions are doubled, an idea of a real crossbow is arrived at without too much

trouble. The nocked arrows then are seen to be just under 28 inches and the bow would be

about 55 inches long mounted on a stock of almost 31 inches. The cross-sections of the bow

can be guessed from the photographs and they suggest a bow with broad lenticular working

limbs tapering to triangular (or pentagonal) tips. The point where the binding occurs

looks to be where the working limb stops. This bow is on the way to needing reinforcing

bone strips at the nocks.

Two bars project from the front of the chariot on the centre of the left side. They are tipped with curving hooks of the type, which were though once to be mounted on the stock of the crossbow to mount the bow. This is where the crossbow sits when it is not in use. The bow is held by the hooks and the trigger guard leans against the sloping frontpanel of the chariot. If the stock were slid between the two bars, with the bow underneath, then the archer could draw the bowstring up to the lock more easily. I had often wondered how a strong crossbow could ever have been braced in a chariot.

I hope you find this interesting. I have received an e-mail from Dr Grayson and I am going

to send him a copy of this information.

Stephen Selby

I have inspected the reconstruction personally, accompanied by one of the people who worked on the excavation, Prof. WANG Xueli. He made the point to me that no matter how many original crossbow stocks have been excavated, no prods have ever been found. Not even the traces of where they had been. He and I agree that the bows were never buried with the stocks. The Qin crossbow was simply a firing mechanism for the bow, which could be removed and used as a normal bow. Each such bow required three years to manufacture, and although they were sometimes buried with tomb occupants, the burial of large numbers of such hi-tech items with models of occupants (i.e. the teracotta warriors) would have been an improbable waste of strategic materials. The bronze model (1:2 scale) is therefore the only indication we now have of the form of the original.

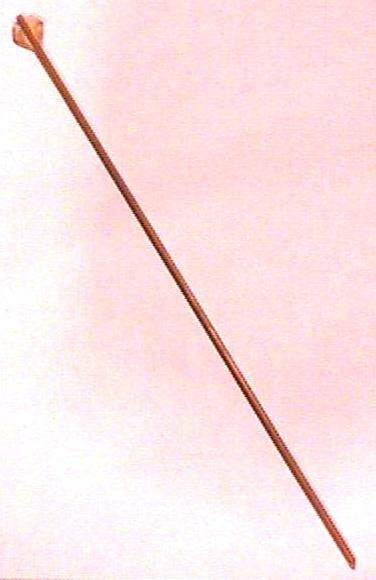

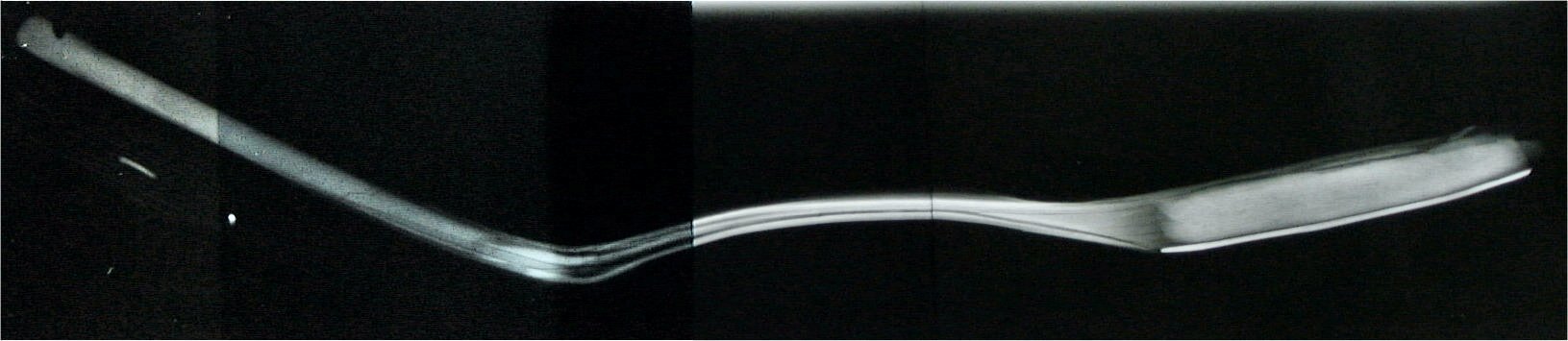

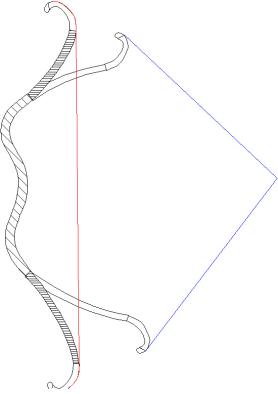

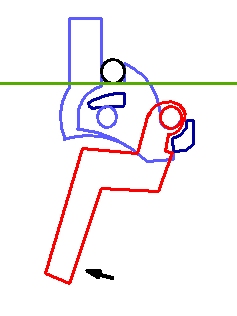

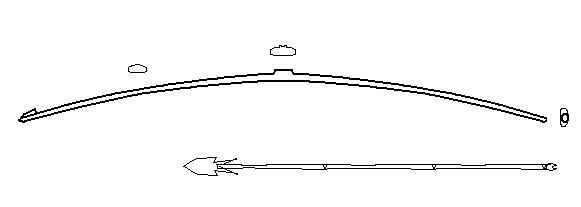

Prof. Wang's restoration of an actual crossbow (i.e. not the bronze model), based on remains of crossbows he excavated, is as follows.

I think this looks quite reasonable, and I wonder whether the 'inner cord' was placed on the resored bronze model in mistake for the diagrammatic view of the string positions in Prof. Wang's illustration...

This is my own restoration of the actual crossbow in use -

Bede Dwyer

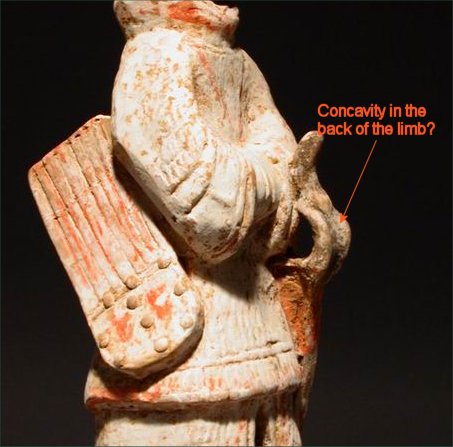

The picture of the bronze model crossbow you are placing on the web page sems to show a swelling of the tip of the bow to accept the bowstring. Do you remember what the shape of the tip was? Was it flattened from side to side with an indentation on the back of the bow for the bowstring?

Stephen Selby

Yes. This slightly oblique photo shows that more clearly.

There was flattening, but I don't think there was any intentation or string nock.

Bede Dwyer

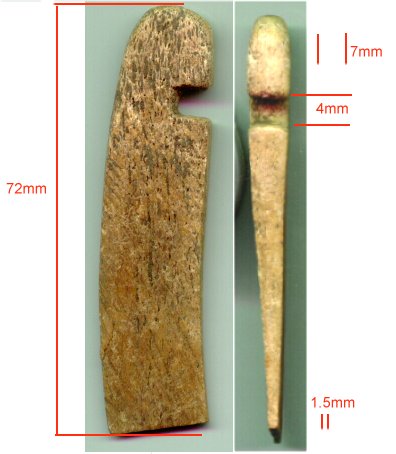

I am curious to find the earliest appearance of the single nock on the back of the

bow as a method of attaching the bowstring. I think I sent you a photocopy of an article

on bone/antler bowtips in China from Wenwu.

Stephen Selby

Jade bow tips excavated from a Shang tomb at Anyang imply this sort of nock. Presumably the development of string nocks suggests the use of loops at the ends of the string, and maybe that further suggests the introduction of the endless loop as a method of making a string...? Also, I understand that a long, freely-moving loop would be necessary if long static tips (sayahs) were to work properly. So would that leave little alternative to using string nocks on the back of the bow?

Bede Dwyer

My question is now: why were there two string positions? From the photographs of the chariots in situ, I thought that the bow was cast in a braced state.

Stephen Selby

If there were two strings, it may be that they wanted the bow not to relax completely when unstrung. The smaller string might have inhibited the bow from relaxing to a position that it would be difficult to re-string when required without removing it from the stock and using a brazier and tepliks.

Bede Dwyer

The suggestion that the bows could be dismounted and used as hand-bows is very interesting. I admit that I was wondering along those lines too. Is there any indication in the texts?

Stephen Selby

I think that later (Han and after) crossbows did have specially-constructed prods. But

I believe the earlier ones used general-purpose bows mounted on a stock.

My main reason for thinking that is the way bows and crossbows are discussed in the 'Rites

of Zhou'. The "Rites of Zhou" (you have seen and commented on my translation of

'the bowyer') mentions crossbows several times. It dates from the late Warring States

period (about 450BC) and is thought to represent the system operating at that time in the

state of Qi. Although it contains detailed instructions for making different types of

bows, there is no mention of making crossbow prods or stocks as a separate exercise.

In the description of the duties of the 'Gao Ren' ('mat man'), the Rites of Zhou says:

"There are six types of bows in three categories; four types of crossbows in the same

manner.'

The section on the 'Si Gong Shi' ('bow and arrow manager') it says: "In distributing bows, arrows, crossbows and quivers, the 'wang' and 'gu' bows are for teaching shooting to penetrate armour, wooden reinforcement and shields; the 'jia' and 'yu' bows are for teaching target shooting, fowl and wild animal shooting; 'tang' and 'da' bows are for archery study, demonstration and exercise. As regards crossbows, the 'jia' and 'yu' are for shooting against fortifications; 'tang' and 'da' are for chariot battles and warfare on open ground..."

The lack of differentiations in the names of the bows suggests to me that the primary consideration was the basic bow type, and the bow was then attached to the stock as needed.

June 1999

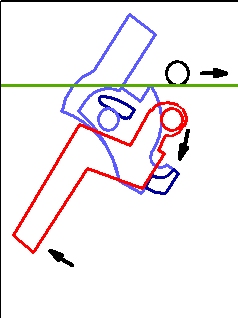

In Peking, I spent some time interviewing an old Chinese bowyer about the history of his family's bow workshop, which started in the Qing Dynasty under the Emperor Qianlong (in about 1750) and operated up until the Cultural Revolution in 1966.

Some members have asked me whether Chinese traditional bows can be obtained nowadays. ATARN is now able to offer reproductions of Chinese traditional bows; but they are suitable only for decoration and historical enactment: not for serious shooting. I say this because they have been made recently using a bamboo core backed with glass fibre, decorated with lacquer and snake skin. This certainly gives a convincing appearance of a Chinese bow: but their shooting qualities are poor because of inferior materials and workmanship. The bows are ambidextrous and pull at about 28# - 32#.

The cost of these bows is US$130, plus shipping. Do not order these bows for serious archery purposes. Do order if you want something interesting on the den wall, for enactment, or for getting the correct proportions for making your own Chinese or Mongolian bow. I shall be bringing a few to Denton Hill in July.

Meanwhile, with ATARN's help, I am dedicated to helping to revive the ancient, traditional bowmaking craft in China, and I shall strive to bring you fully-functional Chinese bows and arrows in due course.

I also have a supply of pre-cut water-buffalo horn for bow-making. Each matched pair is about 60 cm long by 4 cm wide coming to a point at the top. They cost US$50 per pair plus shipping.

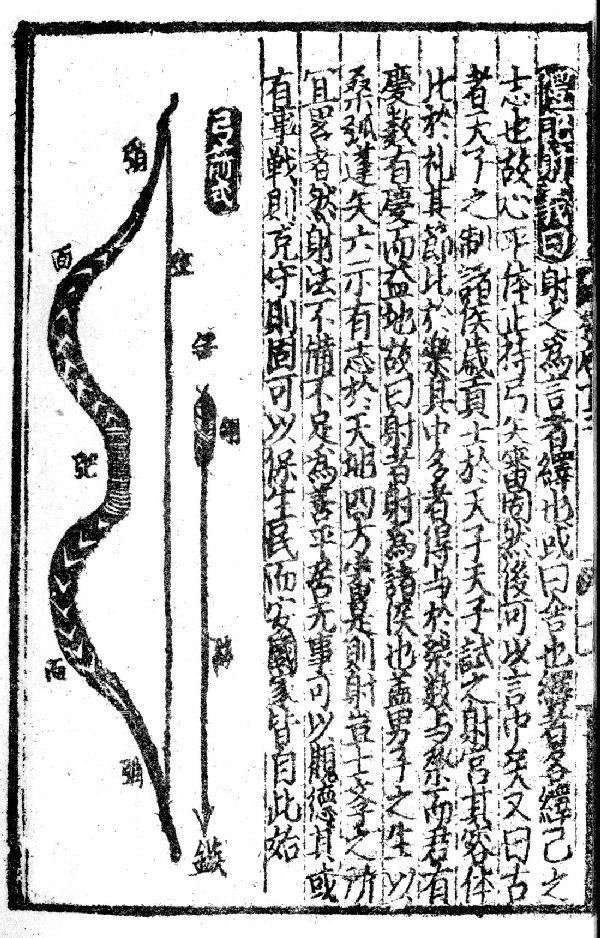

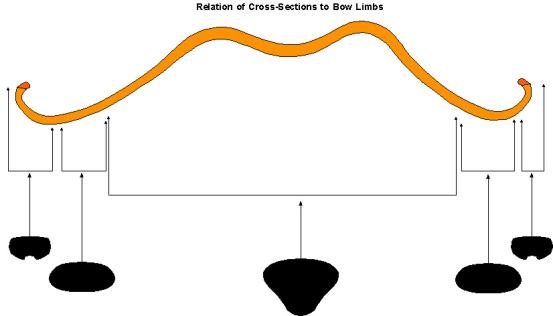

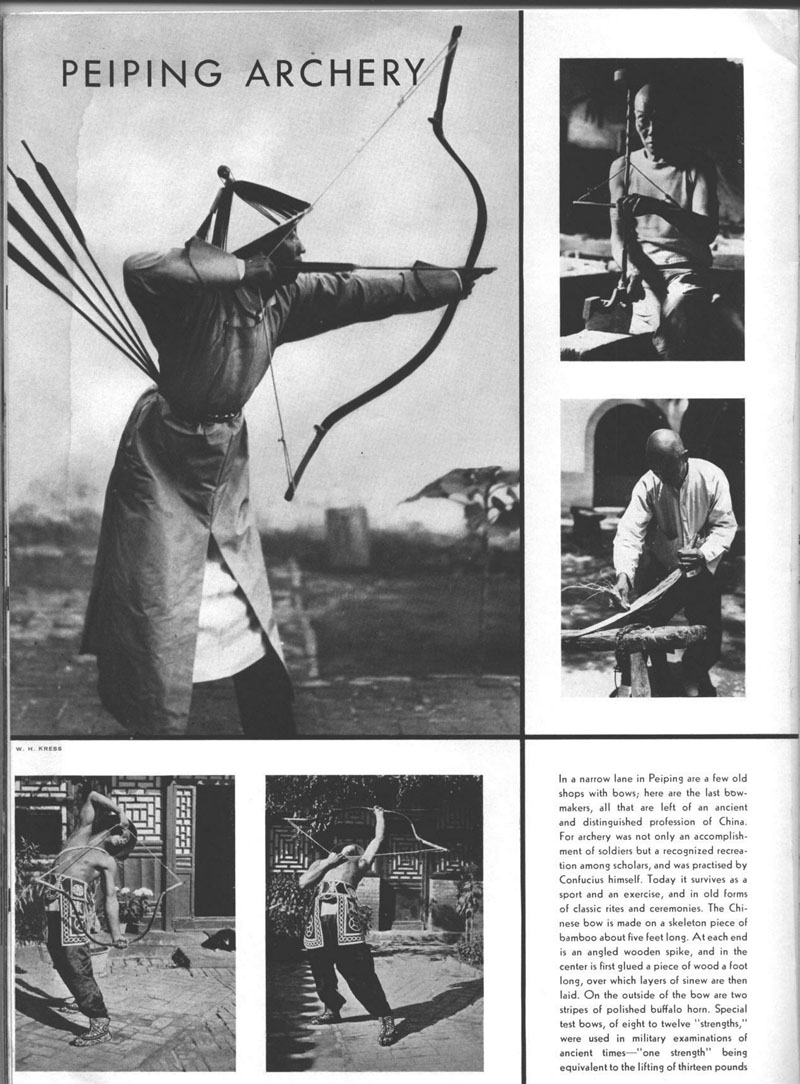

Pellet-bows

I had a chance to study some interesting traditional Chinese pellet-bows. The bow itself is quite light, backed with sinew but without horn. (One such bow, however, had been converted from an arrow-bow which had broken and is horn-backed.) They were decorated with snakeskin and often had tips carved in the shape of a monkey's head.

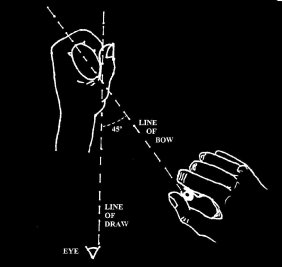

The most extraordinary part of the pellet-bow, however, is the string. It is made up partly from silk bowstring and partly from rigid bamboo straps. A small cup of carved bamboo covered with sharkskin holds the baked clay pellet. The bow is drawn with the bow-hand grasping the grip below centre, imparting and outward torque to prevent the pellet from hitting the grip when the string is released. The draw-hand thumb and forefinger grip arround the cup, holding the pellet in against it. This is easy because the draw-weight does not exceed 25#. The pellet cup is drawn back to the archer's eye, and the shot is made aiming at the target past the top of the grip (which is aligned level with the pellet-cup.)

Pellet set in the pocket of the Chinese pellet bow.

This sort of bow was popular for shooting at small birds. The shot is supposed to be non-lethal: the idea was to catch birds live: not to kill them.

Yunnan Province is home to 26 cultures (including Han Chinese, Manchus and Muslims.) Many of these cultures (Shan, Khmer, Dai, Miao, Nu, Bai and Jinu) are renowned in history for their use of the crossbow. In fact, historical and archeological remains show that these tribes used the stonebow and crossbow but not the conventional arrow bow. They were famous for their use of powerful poisons on their arrows.

|

Wooden crossbow from the Nu minority, Yunnan, China |

I was able to obtain three of their traditional crossbows, goatskin quivers and bamboo darts, as the Chinese government has recently banned all hunting in their areas as an urgent wildlife conservancy measure.

|

|

|

| Crossbow quiver of the Nu Minority of Yunnan, China | Nu crossbow dart (bamboo) | Fletching using bamboo leaf |

Later I shall put up an article on the crossbow culture of Southwestern China.

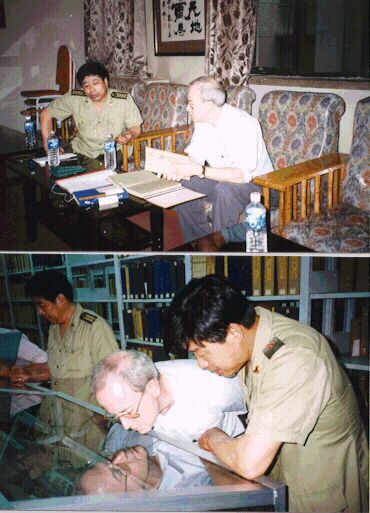

Chinese People's Liberation Army

In Peking, I paid a visit to the Academy of Military Science of the People's Liberation Army, where I was able to study old books on Chinese archery in their archive. Staff at the Academy were very helpful and supportive of our work. After my visit, during which I introduced ATARN, staff at the Academy wrote in an email (in perfect English): "The website of ATARN is great and I believe that some people in our Academy would surely like it. "

Studying Chinese traditional archery and materials in the archives of the Academy of Military Science of the Chinese People's Liberation Army. |

November 1999

I had been thinking for some time of reconstructing the Han standard military crossbow based on the numerous bronze crossbow mechanisms (many in good working order) that appear on the market. Now I have actually done more than think about it: with the help of Ju Yuan Hao of Peking, we have actually made one.

Han Military Crossbow Mechanism

We derived the design from the bronze

model crossbow attached to the bronze chariot in the tomb of the Emperor Qin Shi Huang,

with dimensions as I have postulated in my book, 'Chinese Archery'. There is also a wealth

of illustration on Han dynasty tomb bricks and stone carvings to give us a good idea of

how these crossbows looked and how they were used. There are some reconstructions in Yang

Hong's 'Weapons in Ancient China' (Science Press, New York/Beijing, 1992), for example on

page 200.

We derived the design from the bronze

model crossbow attached to the bronze chariot in the tomb of the Emperor Qin Shi Huang,

with dimensions as I have postulated in my book, 'Chinese Archery'. There is also a wealth

of illustration on Han dynasty tomb bricks and stone carvings to give us a good idea of

how these crossbows looked and how they were used. There are some reconstructions in Yang

Hong's 'Weapons in Ancient China' (Science Press, New York/Beijing, 1992), for example on

page 200.

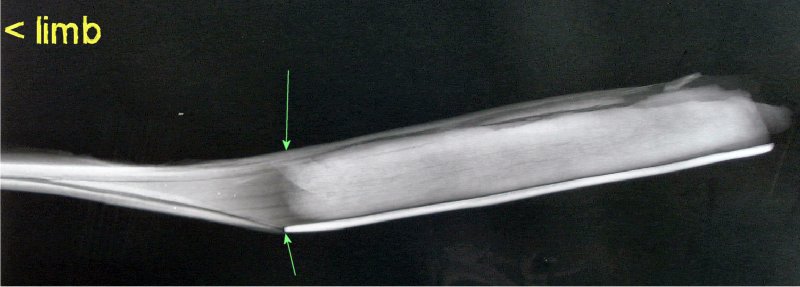

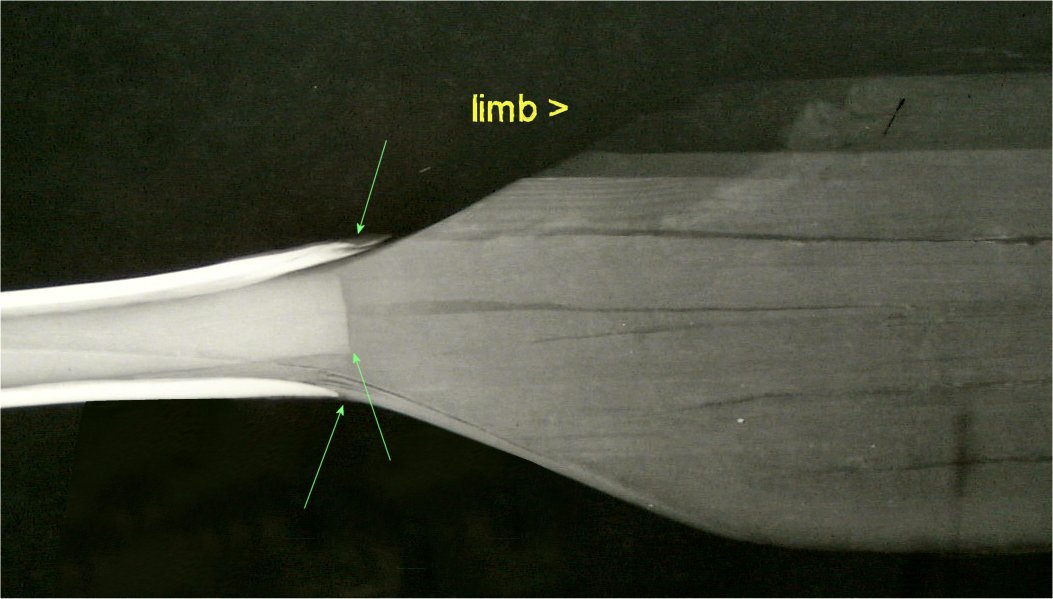

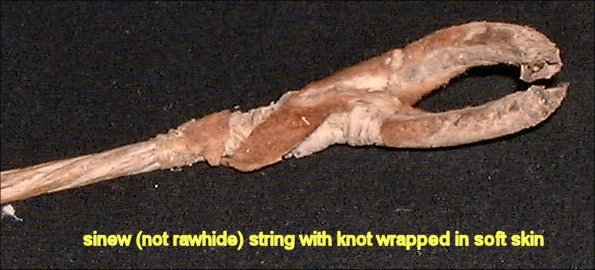

Ju Yuan Hao developed the design for the prods on the basis of a normal bamboo/horn/sinew composite bow with a draw weight of 60 pounds. (This low crossbow draw-weight was just for ease of experimentation: he will follow up with a weight of about 100 pounds.) The prods form a separate entity, mounted on the wooden stock and bound onto the end of it with thongs. The string is made of wound rawhide. The mechanism is an original Han dynasty bronze mechanism in good working order.

The result is a solid, workable weapon which takes down into a handily-transportable form. The bow itself stacks badly and is not of much use for shooting on its own.

|

|

|

There's a good chance we'll be able to manufacture this crossbow commercially at a reasonable price when we've got the kinks out. Obviously, we don't plan to equip every one with an original Han dynasty crossbow mechanism so we'll have to enquire about having the bronze mechansims manufactured for us at a reasonable price. The original mechanisms were cast and then hand-finished; but today it would seem preferable to mill them.

Please let me know if you have any advice on this project, so that we can get the crossbows really good.

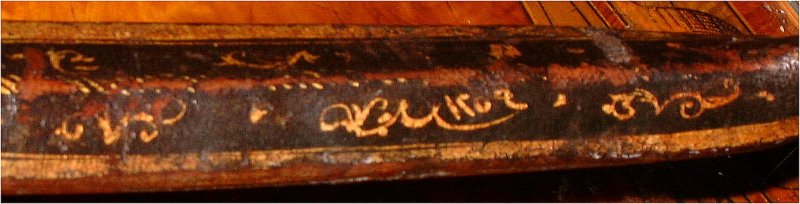

Talking of crossbow mechanisms, a few mechanisms have turned up in North China which, on the basis of style and calligraphy of the inscriptions, appear to be Tang. The sight feature on all the specimens is in the shape of a stylized lion. The latch and trigger have turned up, although I have not yet seen a lock or the axles. I show the items below (if the image is too small, download to your terminal by right-clicking the image, and blow them up with your own graphics software. I will not claim copyright on them.)

Latch and trigger |

Details of the decoration |

Reconstruction of the whole mechanism |

An interesting feature of the latch is that all three specimens I have obtained have pits gouged from the sides as if to make them balance properly. One mechanism bares the maker's mark 'Er yu' while the other one has the mark 'Zeng'.

Please let me know if you have seen such mechanisms before, and any information you have on them.

February 2000

A Writer’s Dilemma

or

"I thought they all had Ninjas"

by

Gwen Huskins

I am the first to admit that historic fiction of any sort is a great challenge. Woe to any author who mixes names or locations. However, it seems to me that any historic fiction that does not take place in Britain or North America post-1066 requires extra effort. Research books are available, of course, but these for the most part ignore all but Anglo-Saxon cultures.

The Orient especially seems to be susceptible to misinformation, ignorance and to some extent, smugness. This attitude dates back hundreds of years. A good example is the self-satisfied description of opium smoking in The Historical Encyclopedia of Costume by Albert Racinet. Dr. Aileen Ribeiro points this out in her introduction. "…(Racinet was) becoming particularly indignant about the opium smoking habits of the Chinese Imperial Court: whether or not they existed, he seems to ignore the notorious involvement of the European powers in the opium trade with China."

On the opposite end are individuals whose education of Asia has come primarily from watching Karate Kid. This seems to be the most common problem here in America, thus the subtitle of this article. "Ninjas were everywhere, didn’t you know that?" is the general attitude and all other weapons of Asia that weren’t featured in Teenaged Mutant Ninja Turtles are ignored. I must admit that I was among the ignorant until recently.

The research problem I went to ATARN for was an inquiry on the Chinese repeating crossbow. This weapon is represented in movies (most notably the Shadow) and video games (most notably Age of Empires II) as a sort of medieval Chinese Uzi with the same power and destructive capabilities. It naturally never jams although that can be argued as being a cinematic necessity.

Another mistake that seems common is that even when Asian archery is represented it is assumed that European and Asian archery are exactly the same thing. This makes about as much sense as saying that since the Chinese and Europeans enjoyed silk their fashion is identical or that since Japanese and English swords are both made of steel then there is no difference between them.

The best idea for a historic novelist is to find an expert or a reputable history book and leave Hollywood out of it.

May 2000

Ju Yuan Hao also sends his greetings to ATARN Members. The son of the family, a man in his forties, has now firmly taken up the task of learning bow-making from his father.

'I am really trying to get into this,' he told me. 'I realize the weight of responsibility upon me. I feel rather like a monk who has taken vows. I am up at the flea market at five o' clock on Saturday mornings to see if there are any old broken bows about. When I can get them, I take them apart to learn how the old masters worked and then put them back together again.' (He has put a handful of old bows back into shootable condition, although some of the draw-weights are extremely heavy.)

'You probably don't realize what a challenge this is for me. In the old firm, there were a number of people involved and we outsourced a lot of activities. In the workshop in my father's day there were three or four people working on the bows, and then a number of people working on the decoration. There was a tradition of keeping these activities separate: the bowyers did not do decoration and the decorators did not make bows.'

'What's more, most of the materials came to the workshop pre-worked. We could take the parts of the horn that we wanted (just the flat, outside curve of each horn) and all the rest (save some scrap for the tips and string-bridges) went to the comb-makers' guild. For the siyahs, we needed elm wood with a slight curve to the grain. The woodsmen knew what we needed and we could always get it. Now all we can get is industrially-cut wood. You're not allowed to go around Peking cutting up trees any more.'

'Now I and my father are having to face the whole task of sourcing and selecting materials, as well as doing all the bow-making together with the decoration. That's a completely different situation from what happened in the past.'

'Another problem is that Father can't pull a bow any more, and his hearing is going. A maker of horn and sinew bows has to be able to hear the bow as it is pulled. Imminent failure carries warning sounds, and you can detect defects by tapping the limbs. But father can't tell me what to listen out for any more, so we sometimes have some dangerous catastrophes. I'm learning to pull a bow now: I can already manage fifty pounds.'

In a Peking antique market, I had an exciting find: a little iron model bow and arrow.

Liao model bow. Arrow shaft in front of the string: 3.8 cm.

Height: 11.7 cm. Max width of limbs: 0.65 cm.

This seems to be a Liao (Khitan) burial item dating from around 12th Century. The Khitans were the political predecessors of the Mongols whose name gave rise to the word 'Cathay'. This little bow was once gilded and a lot of attention seems to have been given to detail. The grip and the relative thickness of the limbs look convincing, as does the twisted rawhide (or gut) string. The arrowhead is typical of the Liao iron arrowheads I find in Peking. In the model, the arrow nock is a ring which fixes the arrow so that it can swing on the string. The arrow is triple-fletched. Ju Yuan Hao will make a full-size replica.

July 2000

I've been on the move again, and I'm holding down two jobs here, so time is hard to find. Anyway, my schoolteachers never accepted such lame excuses, and I expect you won't either.

I found an interesting bow in London. An antique dealer had had a Japanese yumi in his shop for months and couldn't shift it because it was too big for anyone to want to take it away. Originally he had two: one, dated 1737 in traditional Japanese dating, was a fine, lacquered bow and very valuable. The other was a much plainer bamboo-wood composite yumi of no great age. Finally, he let me have it at a knock-down price and it came in the luggage hold to Hong Kong.

A member asked me the other day how I take big bows by plane. Actually, I've done it a few times. Never box them up. Although it looks safe, airport staff have no respect for anything in an anonymous box, and serious damage may ensue. Instead, wrap the bow (unstrung) in several layers of bubble-wrap, paying special attention to the bow-tips, grip and string bridges if they are present. Let the 'bow shape' be visible to anyone looking at it. Check into the luggage hold, but as airline staff to put a 'fragile' sticker on it. I have had no accidents yet like this. (Don't try to take arrows as hand luggage: it sends security staff into a spin.)

Back to the yumi. When I got it back, I read off the Japanese maker's name and sent off a query to eClay and Yoshiko Buchanan.

They came back with the exciting news that the bow was a special one made by one

of Japan's leading recent bowyers, Higo Saburo. Higo made a number of special

bows that he was in the habit of giving away to valued friends and eminent

archers. eClay says that Higo made up a proverb saying that the archer should

"listen for the frost climbing up the ridgepole of a traditional Japanese

hut." That was a reference to the subtle cracking that a Japanese archer's

glove gives out as the string is drawn back.

To show my gratitude, I am presenting Members with a copy of something else Japanese that I picked up in London's antique shops: two magnificent Ukio-e ('floating world') woodblock prints of Japanese archery by the artist Chikanobu (1838 - 1912).

The prints, dated the second lunar month of Meiji 30 (spring 1898), depict Japanese archery games on foot and on horseback.

I donate these reproductions into the public domain, so members can copy them and distribute them freely (and turn them into Windows wallpaper!)

Target Archery with the Yumi. Woodblock print by Chikanobu, 1898

Horseback archery with the Yumi. Shooting at a running dog with a whistling

arrow. Woodblock print by Chikanobu, 1898

October 2000

Hasman Shah Bin Abdullah is a professor at the Universiti Teknologi MARA in Selangor, Malaysia. Over dinner, we discussed traditional archery and he came up with the following story.

"When I was a kid in Segamet, Malaysia in 1968-69, there was an old Tamil man who worked with the Public Works Department. We just called him 'uncle' in Tamil - I don't know what his real name was. Anyway, he used to make bows and shoot pellets from them. I and the other kids used to help him. We would go into the jungle to collect bamboo, and then he would cut the bamboo and soak it for some time in a mixture of three kinds of oil. I can't remember what oils they were, but I think one was something we called 'salajeeth'.

|

"After soaking the bamboo, he would

put it in a container and bury it under the ground for a few weeks. When he dug

it up again, it was ready for the nocks to be cut. Then we would go into the

jungle again to search for the bark of a certain type of tree. When the bark was

dried out and beaten, it made an excellent bowstring. The strings would be

formed in a parallel pair with a basket woven in the middle to take the

pebble. The bows were too strong for us to brace: Uncle would brace them after

taking a few deep breaths to prepare himself for the effort.

"Uncle used to make pellets out of baked clay. We children were not allowed to shoot with these pellet bows. "If you don't know how to shoot properly with these bows, the pellets will shatter your knuckles," Uncle used to warn us. We used to have flying foxes (a type of fruit bat) in Segamet and Uncle could take one down with his pebble bows." Left: A White Karen from Northern Siam (Thailand) shooting with a stonebow. See picture archive. |

I took off a Saturday from a business meeting in Geneva to visit the workshop of Patrice Canale in Bordeaux, France. Patrice has been making a variety of traditional bows in modern materials and his repertoire includes Mongol-style bows. We spent and afternoon examining a couple of old, broken Chinese bows I had taken with me we shall try to see whether he can reproduce one in modern glass fibre.

Bordeaux is a beautiful city close to outstanding deer and boar hunting country. If you are interested in one of Patrice's Mongol bows, you can contact him at his firm, Euro Archery. (euro.archery@wanadoo.fr)

Sorry to come back to Chinese things; but some interesting old bows have been coming to me from Gansu Province in West China recently. Gansu is a dry province adjacent to Tibet, and it seems that bows are better preserved there than in Peking, partly because of the climate and partly because many people there still know about how to look after bows. One bow I recently obtained was an old, damaged Child's bow. The measurement from tip to tip along the limbs is just 123.5 cm. It is exactly two-thirds the size of a standard adult's bow of the same proportion and design, and perfectly made in the traditional way with horn and sinew, and decorated with lacquered birch bark.

Qing Dynasty Chinese half-size child's bow (123.5 cm from tip to tip along the

limbs)

Unfortunately, the bow is quite damaged. One of the horn tips has broken off and the wood has been squared at the break and a new tip carved into the siyah an inch or so below it, so that the length of the siyahs now differs by about one inch. (I have seen this sort of patch-up in many Chinese and Mongolian bows.) In the illustration above, I have used the computer to restore it to its original appearance. Based on a standard brace height, a Chinese bow has a string length between nocks approximately 0.855 of its length measured along the limbs. Therefore, the string length of the child's bow was approximately 105.5 cm.

I had the pleasure of interviewing

Zhang Shaojie, a performing artist who has devoted his life to performing feats

developed from the old military examination system. His performances included

weightlifting, pulling heavy bows and shooting with the pellet-bow.

Zhang is the fourth generation of performers and he is very well-known in China. From his great grandfather, Zhang Yushan, through his grandfather, Zhang Baozhong, and father Zhang Yingjie, he has developed performing skills based on the feats that candidates for the military examinations in the Qing Dynasty had to perform.

"We had our own performing troupe and a medicine shop as well. We used to perform in the streets behind the Temple of Heaven and sell our medicines to crowds attracted to our bow-pulling acts," recalls Zhang. Later on, we formed into a proper performing troupe in a circus performance. We had bows of over 100 pounds draw-weight and we performed feats of strength with several of these bows linked together."

"Another act was lifting a heavy stone. Actually, the stones were horse-mounting blocks called 'zhishi'. First we lifted them with two hand onto one knee, then after preparing, we lifted them high enough against our chests so that the audience could see the bottom of the stone. The we put them back on the ground."

So you thought you knew what a 'bow knot' was?

© Zhang Shaojie, 1999

"We used to make our own pellets for the pellet bow act. Everything went into them: hair, paper, lead and clay. Then we baked them hard. The act we performed required using a pellet to put out candle flames at a range of a few metres. My wife is the crack-shot at that. But now neither of us performs and we do not take on any students. It just takes too much time for practice. No-one has the time for that these days. And the other thing is, it's difficult to make an attractive stage performance out of shooting with a pellet bow."

"We used a pellet bow with two parallel strings. If the draw-weight is heavy, we can use a thumbring. You draw the string back to the corner of the right eye and aim over the left thumb at the target. As you release, you twist your left hand outward slightly to avoid hitting your thumb. Hitting you thumb is called 'jiao mer' ('calling out at the doorstep'). We couldn't take bows made in North China down to the south because of the humidity. My grandfather used to get lacquered southern bows made in Fujian."

Zhang Shaojie pulling a heavy bow during a performance. © Zhang Shaojie, 1999.

Zhang Shaojie is preparing to recreate his act for the symposium in May. He asked me what he would have to do to join ATARN. He was surprise to learn that anyone who regards him or herself as a traditional Asian archer is automatically am member!

A member has asked me whether I had pictures of tools used to make traditional Mongolian and Chinese Bows. When I was in Mongolia, I found that the bowyers were using western industrial tools; but with the assistance of Ju Yuan Hao, I have prepared the following group of photographs. (© Stephen Selby, 1999. Copyright reserved.)

December 2000

As

usual, I am at a loss for anything to write about anything other than Chinese material.

But at least I'm not at a loss for Chinese material to write about.

As

usual, I am at a loss for anything to write about anything other than Chinese material.

But at least I'm not at a loss for Chinese material to write about.

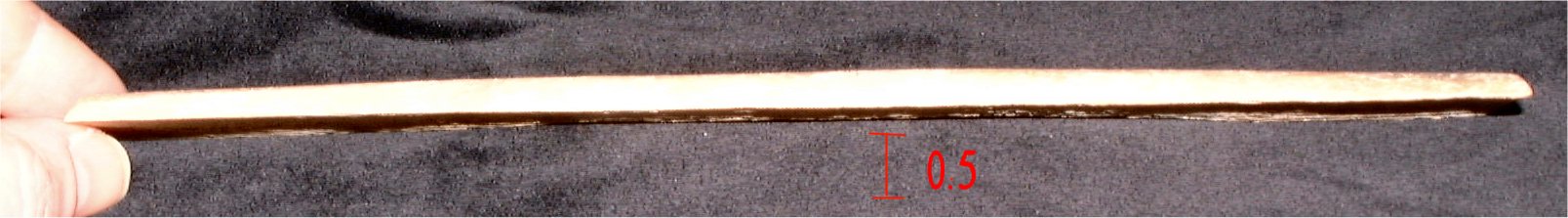

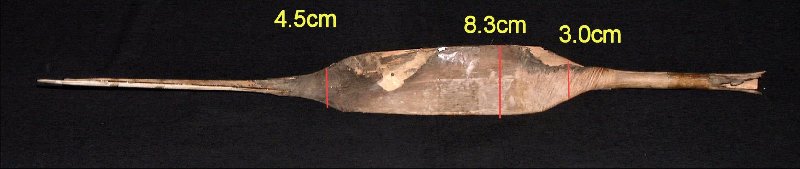

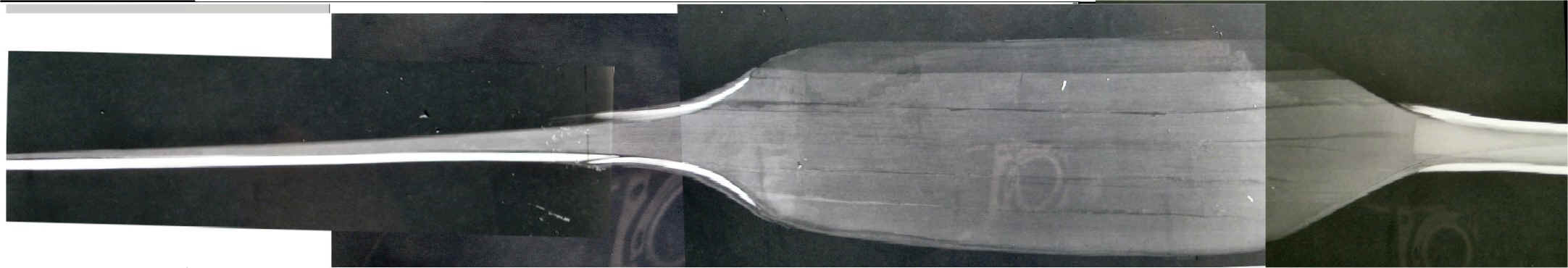

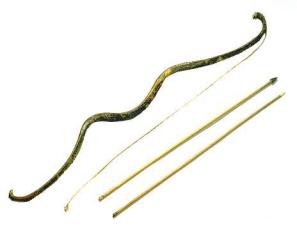

This week, I have had a chance to examine some Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE - 8 CE.) archery equipment. Examining archery equipment that is over 2000 years old is an extraordinary event in the West; but in Asia, with a long history of burial of weapons interred in graves together with their owners, we occasionally get the privilege of examining such material. Last week, some Hong Kong antique dealers and collectors were patient enough to let me take photographs of interesting items. The problem with these items, of course, is that they all lack archaeological context.

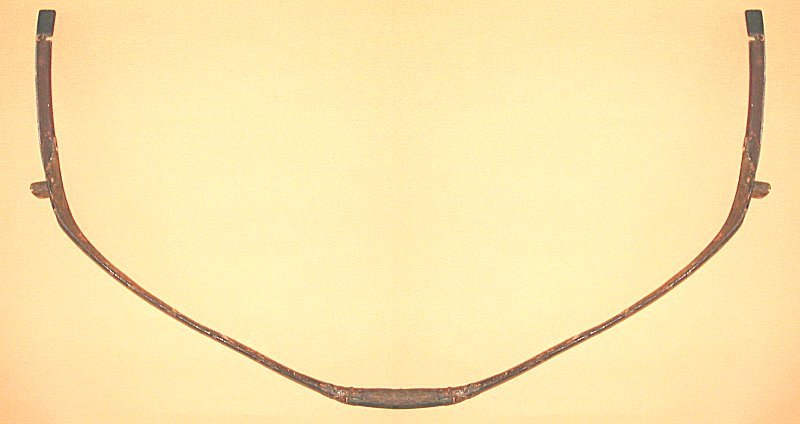

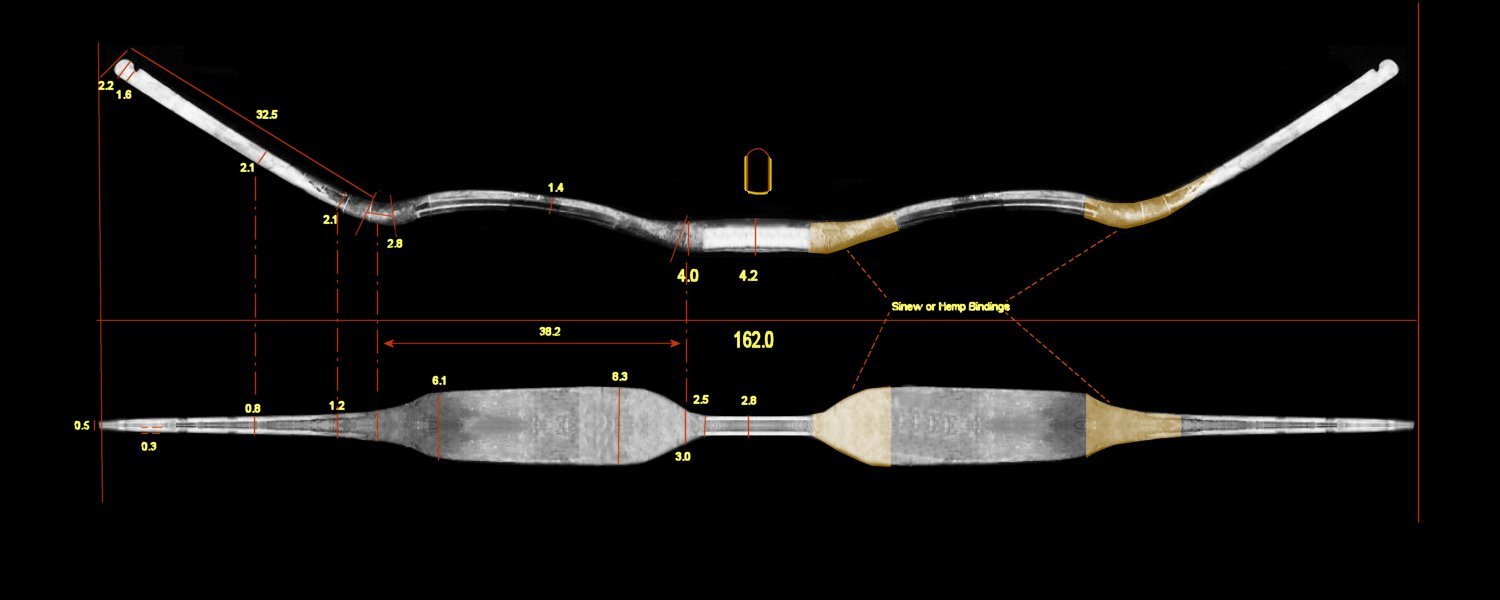

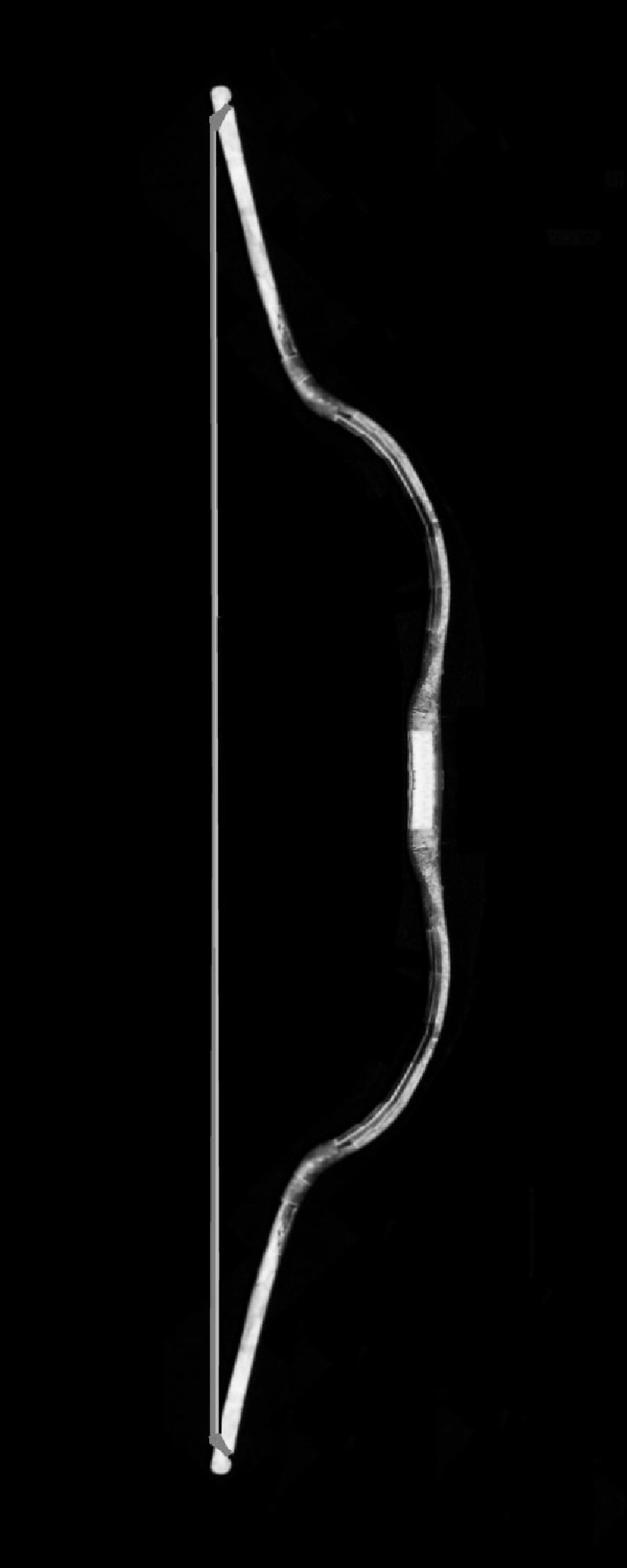

The bow on the left is in fact one that I have owned for some time. I have examined carefully with a microscope. Although it has not been radiocarbon dated, I am convinced it is genuine. Dr Grayson has also inspected it and felt sure it was made by a bowmaker - not by a faker.

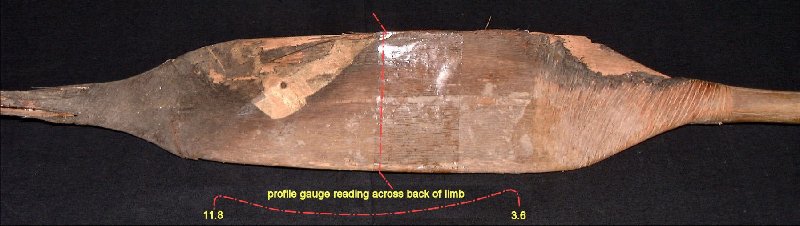

You have my permission to save the this, full-size image on your own hard disk, and then open it in your own graphics editor software. The view you have here is of the back of the bow. You should examine it at 1:1 scale.

The bow is 159cm long and 3.4cm and 1.4cm thick at the widest point. Looking at the descriptions of Neolithic European bows on p. 91 of 'The Traditional Bowyers' Bible', Vol. 2. (Ed. Jim Hamm, Bois d'Arc Press, 1993. ) the positioning of the grain most closely resembles that of the Holmegaard bow. Like the Holmegaard bow, there is some doubt as to which face was the back. The rounded grip suggests that the flatter side of the limbs formed the back; but the string nock is cut with a slant in a way that suggests the opposite.

The grip is cut at a point where there is a significant ring in the grain. Out along the limbs, the grain is very symmetrical. I have not been able to identify the wood. What is unusual in this specimen is that is has been preserved dry and has hardly distorted significantly in any dimension. The wood is very dense and if I strike it when it is suspended, it rings out with a clear musical tone.

I have examined many contemporary early Han images of shooting arrows with bows, and it seems clear to me that this bow would not have supported the draw-length in vogue for arrow shooting at that time. I think it more likely that this was a pebble bow, strung either singly to shoot pellets with a groove, or single- or double-strung in bamboo with a pocket. A pebble bow is only drawn to the corner of the eye, and this bow should have met that requirement (although with a prodigious draw-weight.)

Excavation of Western Han Chu tomb burials near Changsha illustrate lacquered self-bows with an identical design and length.

The Neolithic Ashcott and Holmegaard bows pre-date this specimen by some 2000 years. The similarity of design is, however, startling. Contemporary Han pictures of bows and archery equipment do not illustrate this sort of equipment. However, even around 1300 BCE, there were oracle bone script characters denoting pellet-bows. Excavations have also uncovered pebbles with a channel sawn in one face to take a string.

Han bows used in warfare against the Huns were clearly horn/wood/sinew composites suitable for shooting on horseback. Although we see these bows depicted in stone carvings, the convention at the time was to depict things side-on. We therefore have little chance to assess any detail about the thickness of Han bows. Although I have come across accounts of Han horn bows being excavated in burials, I have never seen an original one or even a good photograph. The best approximation is the type of bow excavated from the deserts of Turkestan, (for example, the Niya bows) which are normally of late Han or Jin design. There is some doubt as to whether these bows were 'Chinese' in any sense.

So I was particularly interested to come across a terracotta high-fired Sichuan funerary military figure grasping a bow in his hands. I have two Han pottery archers, but in both cases, the bow was made of wood and has long since rotted away. The bow with the Sichuan figures, however, is modeled in terracotta. The figure and the bow are both a little stylized: for example, the curvature of the soldier's boy is exaggerated and the bow is molded to the shape of the body.

All photographs copyright Stephen Selby, 2000. All rights reserved.

|

|

In these photographs, one is immediately struck by the breadth of the limbs. This bow is hardly different from a nineteenth century Indo-Persian bow that I have. The segmented band visible behind the bow does not seem to be a string. It is either a strap on the soldier's uniform, or some other device such as a bag for the bow.

Is the bow strung? Perhaps not. There is no sign of a string, and without any sign of string bridges, the alignment of the siyahs is rather unlikely for a strung bow. The general appearance of the soldier is more at ceremonial attention than in a battle position, so it is possible that he would have had his bow un-strung. (I have noticed that the Mongolians were always un-stringing their bows in warm weather as soon as they had finished a round of shooting.)

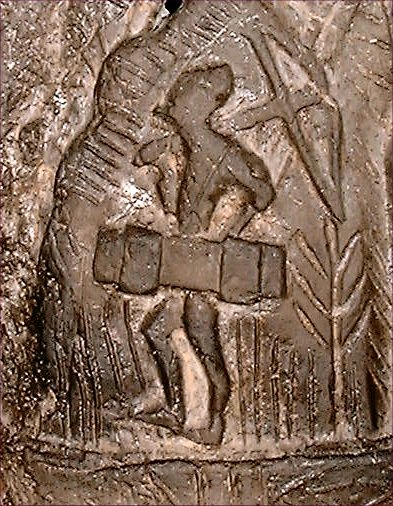

My final report is of a fine, late Warring States Period (c. 250 BCE) lacquered crossbow.

Warring States Crossbow: Side View. bout 65cm

Warring States Crossbow: Side View

Top view

Release mechanism housing

Seating for prod and peg for prod binding

Decoration forward of finger grip molding

Finger grip molding

Top of latch with bone or ivory arrow-guide

Front of stock with binding pegs for the prod

This crossbow is exceptionally well-preserved. The prod is not present and probably never was. The crossbow was in a basket, minus prod, accompanied by a small wooden box with partitions of a size that might have held quarrels (but there were no quarrels in it.) All the items are completely waterlogged. The latch, however, is made of non-corroding bronze and still moves freely.

The wooden box excavated with the crossbow

Artistically, the painting on the lacquer is more reminiscent of early Han decoration, but the design of the mechanism is more archaic, lacking a bronze casing. The floor of the arrow guide surrounding the latch is made of bone. The channel of the arrow-guide is also lined with bone or ivory. Strangely, there is a corresponding channel on the underside of the stock.

I can only speculate on the composition of the prod. It is might have been horn and sinew. Other alternatives would have been a self prod or a number of layers of bamboo. There is no sign of ware. This crossbow has probably never been fired.

January 2001

In

China, it is the custom to celebrate the lunar new year (Wednesday 24 January is

the first day of the Year of the Snake) by cleaning and decorating the house and

putting up auspicious new year pictures.

In

China, it is the custom to celebrate the lunar new year (Wednesday 24 January is

the first day of the Year of the Snake) by cleaning and decorating the house and

putting up auspicious new year pictures.

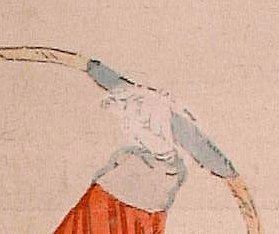

The new year picture on the left is a typical example, although it is unusual. It is a scroll painting which, I should say, dates from the late Qing Dynasty (around the end of the 19th Century) and a slip of paper bears the note "Master Zhang shoots the heavenly dog."

Who was 'Master Zhang'? He seems to have been the same person as 'Zhang the Immortal' (Zhang Xian) who was known from an account dating from the Song Dynasty. Meng Chang set himself up as overlord of the Later Shu kingdom. He took as his concubine the lovely "Lady Flower Stamen".

Meng Chang was defeated in 965 and his concubine was captured and taken to the Palace of the first Song Emperor, Tai Zu. She remained faithful to her husband and kept a painting of him pulling a bow and holding a pellet in his fingers. She hung the painting on the wall of her chamber and made offerings to it each day. When asked by the Emperor why she revered the painting, she deceived him by forging one of the characters of the title . claiming it was a picture of "Immortal Zhang", and that praying to it would make her bear sons. The picture later became the subject of folklore and was used as a symbol of bearing sons.

That is obviously the intent behind this painting, with all the young boys milling about his feet. But I have never seen any mention of him shooting at a dog. Is the black dog the cause a lunar eclipse? (A lunar eclipse is capable of making the moon turn red.)

If you look carefully , you will see that the bow is clearly a pebble bow with a double string, (and, indeed, there is no arrow to be seen.) In the enlargement on the right, you can see that he has a pellet held between his fingers at the grip, ready for the next shot.

February 2001

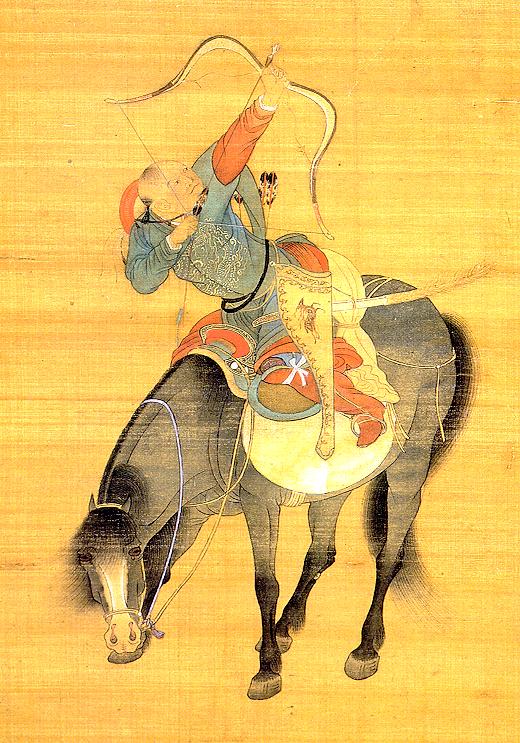

As a feature for this month, I thought I would show some pictures of Mongol/Khitan/Turkik bows from the first 300 years of the last millennium. That is, the bows that were current in the northern part of what is now China in the period from about 1000 - 1350 of the Common Era.

Last year, I showed a photograph of a bronze, model Liao bow.

This little model represents a bow that seems to have been coming into vogue in the Liao-Jin period, around 1000 CE. But this design may have been supplanting another popular design that is depicted quite consistently in artwork dating between the start of the Tang Dynasty and the end of the Song. It may even have had its antecedents in the Niya bows. The distinctive feature of the design was a relatively short working limb with very long, massive siyahs.

Another notable feature of the design is the depth of set-back of the grip, but with a very straight section at the grip itself. The siyahs are very long, starting from where the V-shaped patterning on the woodblock print (perhaps representing birch bark) stops. These bows required no string bridges and are reminiscent of the reconstruction of the Avar bow done by Fabian Gyula.

In fact, if you go back to my reconstruction of the Niya bow (almost 1,000 years earlier), the resemblance is rather striking.

We can see this design in the following images.

Five Dynasties (900-980)

Song. Chen Juzhong

From the preceding images, we can gather that the short, working part of the limb was quite massive and probably broad. The image of part of Liu Guandao's painting, with the servant of Khublai Khan preparing to shoot into the air, has one other strange feature: a fine thread running from the upper to the lower limb inside the string. When he releases, that thread is going to snap taut and the archer is either going to get a nasty cut across his palm, or else the bow will jump forward out of his grip. Anyway, that's his problem, not mine.

This month I am trying out the dangerous exercise of trying to shoot two birds with one pellet. The first 'bird' is to pass on some of my experiences of 'tradition' as it affects Asian archery. The other 'bird' is to introduce some Tibetan bows from Qinghai.

Buryat Traditional Archery near Hailar Banner, Inner Mongolia (Courtesy of © Jin Xiaofang) |

Bhutanese traditional archery (courtesy of ' © Tashi Delek', In-flight magazine of Druk Air) |

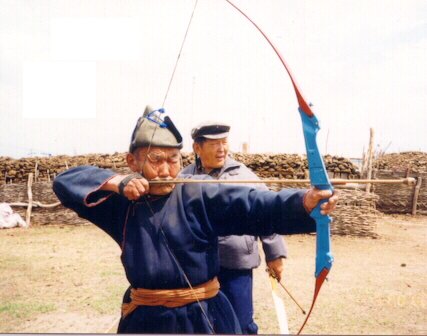

In the West, there is a lot of legitimate interest in the 're-creationist' aspect of traditional archery. But in the more distant parts of inner Asia where traditional archery remains a native tradition, I find few interested in faithfully recreating the past either in terms of equipment or in terms of technique.

Buryat Traditional 'cloth dragon' target (Courtesy of Jin Xiaofang)

A lot has to do with economics. Look at the three photographs above. There is no doubt in my mind that these activities are 'traditional', despite the fact that the archers have (a) obtained western bows and (b) adapted their style to the demands of western bows. Would these archers prefer 'traditional' bows? I don't know. Some will say that they would prefer traditional bamboo or horn and sinew bows, but they can't get them any more. Why can't they get them? Because no-one is making them. Why isn't anyone making them? Because the market for them is too small.

This slightly circular argument may obscure another point: many Asian traditional archers may grudgingly admit (although not to me) that western bows made with modern materials can be more accurate and consistent. Although many traditional archery practices are not primarily concerned with hitting the target, archers who miss do lose face in public. From attending some of these traditional events, it is clear that regularly but elegantly missing the target is not on the agenda. Once one archer has adopted western bows, what are the others to do?

An additional element is the investment of time and resources in maintaining bows and arrows made of traditional materials. Extremes of temperature and humidity affect such equipment greatly. In days gone by, when the bow was constantly at the nomads' sides, it was easier to keep them under constant minor maintenance. Now that they are not called upon other than for traditional sporting events, and are laid-up for long periods of time, looking after them has become more difficult.

There are exceptions, of course. In outer Mongolia, where archery is one of the 'three manly sports' at the national-level Nadam competition, traditional equipment, targets, costumes and songs are all de rigueur. The traditional technique, however, is largely optional. The bows discussed below also reveal a dedication to traditional equipment in Northern Tibet.

Why do Central Asian people persist with any traditional element in their archery, then? The answer does not seem to lie either in any nationalistic feeling of superiority about their equipment or their techniques. Rather, it seems to be to do with asserting a part of their national characteristic represented by archery. When I look further-afield to Korea and Japan, a different picture emerges: these two great archery traditions incorporate a layer of influence from China in which competition is secondary and ritual detail is an important element of the overall procedure.

March 2001

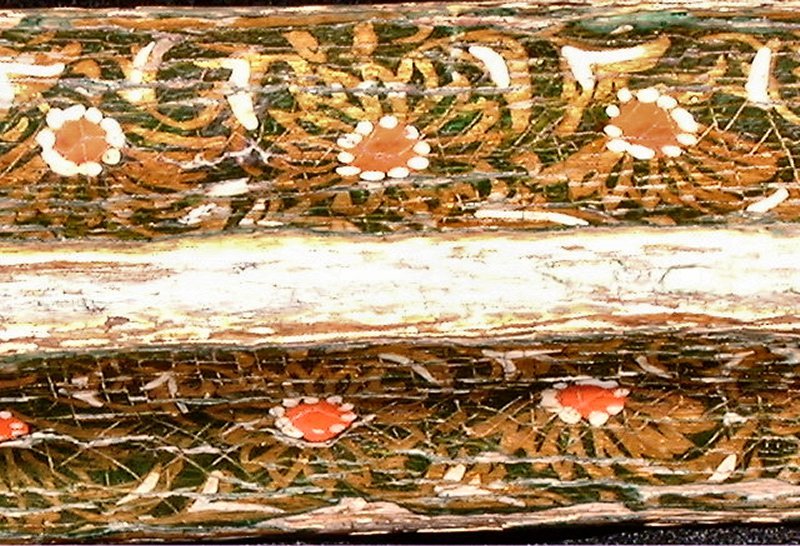

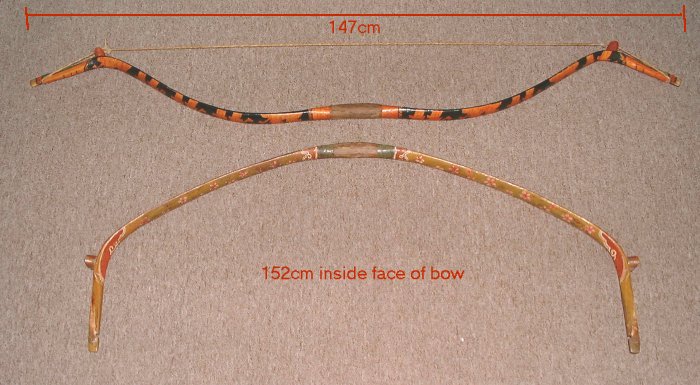

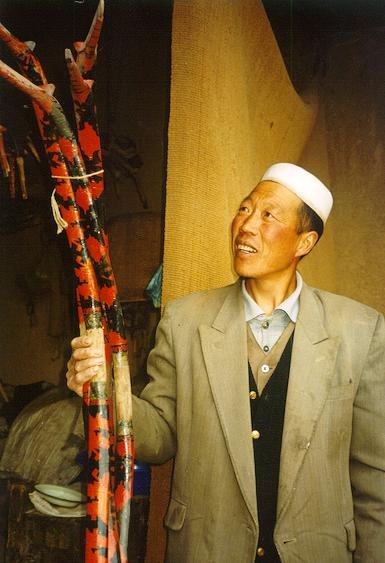

In recent months, ATARN Member Xu Kaicai (a Chinese national archery coach who travels very widely in China) has drawn my attention to some fine traditional bows from Haixi (Tib. Tsonub) Prefecture of Qinghai Province, West China. These bows are made and used by the Tibetan nationality.

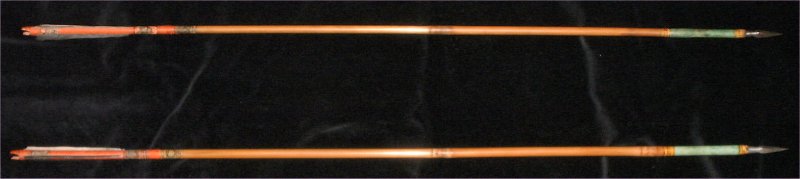

Two modern Tibetan horn/sinew bows from Haixi Prefecture, Qinghai Province,

China.

These two bows are close to Chinese and Manchu bows in their construction, although they are much smaller. The ethnic mix in Haixi Prefecture, Qinghai is complex, both because of a longtime population of Mongols and Tibetans in the region as well as due to forced emigration of Mongols from Inner Mongolia to Qinghai and Gansu at the time of Sino-Soviet tension in the late 1950s.

The bow is smaller than the 'women's size' bows now used in Khalkha regions of Outer Mongolia.

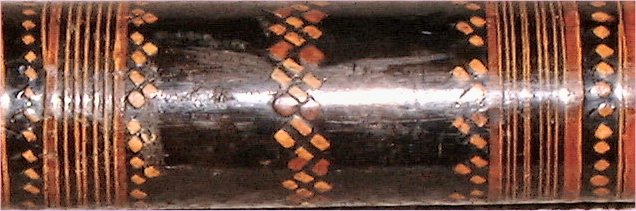

Limb detail and decoration

Siyah detail and decoration. Note the rawhide string.

The bow-tip and string nock reinforcement is in white sheep's horn. The string

bridge is made of wood.

Grip detail. The grip is covered with an unidentified vegetable bark or pith.

Decoration near the grip. All decoration is applied with a black lacquer

paint over natural birch bark.

Antique bows of a similar design. The upper bow is over 100 years old. The

lower one is around 60 years old.

Modern arrows accompanying the bows. Length (nock to base of point) 78cm.

Point: 2cm. The arrows are barreled: 7mmØ at the base of the tip, 10mmØ in

the middle and 5mmØ at the base of the bulb nock.

Details of the arrow decoration. Cresting in coloured silk with lacquer

covering. Shaft decoration in peach bark.

When I talk of these bows being 'made' I am being slightly misleading. The four specimens I have examined (both new and antique) are all made with horn recycled from older bows. I would hazard a guess that in all the cases, the horn came from Chinese bows made in Peking or West China because the dimensions of the horn are identical to those of Chinese mounted archery bows.

The top bow in the first photograph is clearly brand-new. The construction is very sound and the quality of the materials and decoration is superior to modern bows now being made in Mongolia. The draw-weight has not been measured, but it seems to be around 60 pounds (27kg) at 28 inches (71cm).

In terms of decoration, all the bows show strong Chinese influences. The lower bow on the first photograph is decorated with a medlar blossom design (hai tang) - the Chinese rebus for 'elevated rank'. Other decorative elements such as the use of ray skin on the arrow-pass and the key-pattern near the grip are also Chinese. The oldest of the bows has the Chinese character 'wang' ('king') impressed in the horn tip. This may indicate a Chinese bowyer; but 'wang' can also be a sinification for certain Tibetan names.

Are these the bows represented in this illustration from the 1930s? The way

the string is attached to the limb below the siyah cannot be accurate. (Public

domain photo)

The older bow also has repairs done with sinew tightly wound around weak points in the limbs, as well as a wooden build-out below the string-nock to correct a slight twist in the limb. I am told that the oldest bow was the property of a Lama and was shot up until recently in religious sports festivals.

The arrows are almost more impressive than the bows. They are made of wood (probably a common scrub wood known in Chinese as 'liu dao mu' ('six channel wood'.) They are skillfully barrelled and a lot of effort has gone into decoration and finishing. They each have a forged and filed iron tip and an bulb nock.

Two things to say in conclusion. First, there is a fine bowyer out there in Haixi prefecture. I hope to be able to meet him sometime. Second, these bows (and indeed many bows that I have collected) demonstrate the importance of re-cycling of materials in traditional bow construction. I have one Qing bow, which incorporates wood in the siyah bearing a date of the Yongle period of the Ming Dynasty (1403-1424). As there is nothing to make me suspect that the inscription is a fake and the bow is clearly of Qing design, it is likely that the inscription is on a re-cycled part. In many other bows, the horn is of greater antiquity than the wood or the decoration.

April 2001

Members and guests of the Hu Rim Jung Archery Club

My Easter holiday this year with my wife and children took my to Kyongju, South Korea, where we visited Tom Duvernay. This was my second trip to Kyongju, the old capital city of Korea in the Silla Period. My whole family were overwhelmed by the friendliness and generosity of the Korean People (including Tom Duvernay, who - at least in archery terms - should be regarded as an honorary Korean.)

We spent a couple of afternoons at the Hou Rim Jung ('Tiger Forest Archery Club') and I had a chance to study Korean technique close-up. As Tom has already explained in detail elsewhere on ATARN, Korean archery is an ancient tradition with its own styles and precepts, many of which were influenced by China.

The archery range itself is 145 metres in length, commanded by a stone with an inscription in Chinese saying 'Silence During Archery Practice'. This precept is rather honoured in the breach; although things are not allowed to get too rowdy.

There

are three big targets and one small one. A hit anywhere on the big targets is

enough to score (greeted with the comment 'guan juhng' from the judge.) If you hit

the small target, though, you have to pay a fine of 10,000 Korean Won (a bit

over US$8).

In another informal game, players put KW1,000 (a dime) into a Kitty and then try to hit the small target. Anyone who hits takes KW1,000 from the kitty as his prize.

In more formal competitions, a judge sits at a raised table and the archers take their places at fixed positions. Each one shoots in turn as the judge calls his name until they have all shot a round of five arrows.

Shooting at this distance is a wonderful experience for someone like me, hemmed in by the confines of crowded Hong Kong!

Techniques vary a bit, with different archers varying in their stance. Some

position the arrow under the jaw with the string tight against the cheek, while

others keep the string well clear of their faces. All the archers use the

Mongolian draw, although left or right handed shooting is permitted.

|

|

|

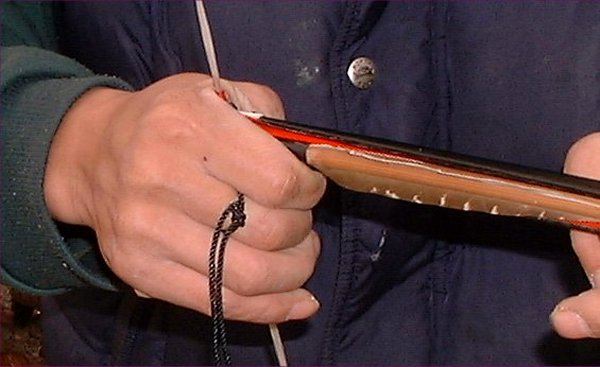

During my stay, I visited Kyongju's renowned fletcher and bowyer.

Master fletcher Choi Geum Dong started his apprenticeship at the age of 17 and studied for ten years.

|

|

|

|

Choi obtains his arrow bamboo from the northern part of South Korea, cut into shafts of about one metre. After curing, the shafts are tipped with brass blunts and a wooden nock is inserted and bound forward of the nock with sinew. Before adding the pheasant feather fletch, Choi has to painstakingly straighten each arrow after heating it over a gas flame.

Master Bowyer Park Gihk Hwan's work has been well-documented in Tom Duvernay's film. Apart from providing a steady supply of beautifully-crafted horn bows, he is trying to create replicas of variant traditional Korean bows such as those presented by the King to generals on ceremonial occasions. He has even ventured into reproductions of Chinese bows.

|

|

|

A special tip from the master bowyer helps to prevent splitting along the grain of the bamboo when the V-splice of the siyah is glued in place: at the top of the V-splice cut into the bamboo, he makes a further very fine (1 mm) saw cut some two inches along the grain of the bamboo. This cut gets filled with liquid glue and helps prevent the tight binding when the bow is put aside to dry from causing the bamboo to split along the grain.

|

|

|

Korean archery is one of the strongest national archery traditions remaining in Asia today. The number of participants is swelling with the inclusion of university students among its practitioners, and this assures trade for traditional horn bowyers and fletchers (augmented by a brisk business in replicas made with artificial materials for novices to learn on.) The Korean Equestrian Association in Seoul boasts a team of horseback archers.

OBITUARY

It is with regret that I report the death in January 2001 after a short illness of Dr. D. Batchuluun, professor of sports medicine at the Mongolian State Sports Institute and a member of ATARN.

Dr. D. Batchuluun (standing on the left)

Dr. Batchuluun was a Mongolian national of Chinese descent who was a fluent reader of Classical Mongolian, Tibetan, Chinese, Russian and English. He was actively involved in research on inner Asian traditional herbal medicine.

It was Batchuluun's firm grasp of the English language and deep knowledge of Mongolian traditional archery that enabled me to bring detailed information about Mongolian archery to ATARN's pages and to Instinctive Archer Magazine. During my visits to Mongolia, he gave up many days of his time to accompany me around the country and interpret the explanations of bowyers and practitioners of Mongolian archery.

Dr. Batchuluun leaves a wife and teenage daughter.

May 2001

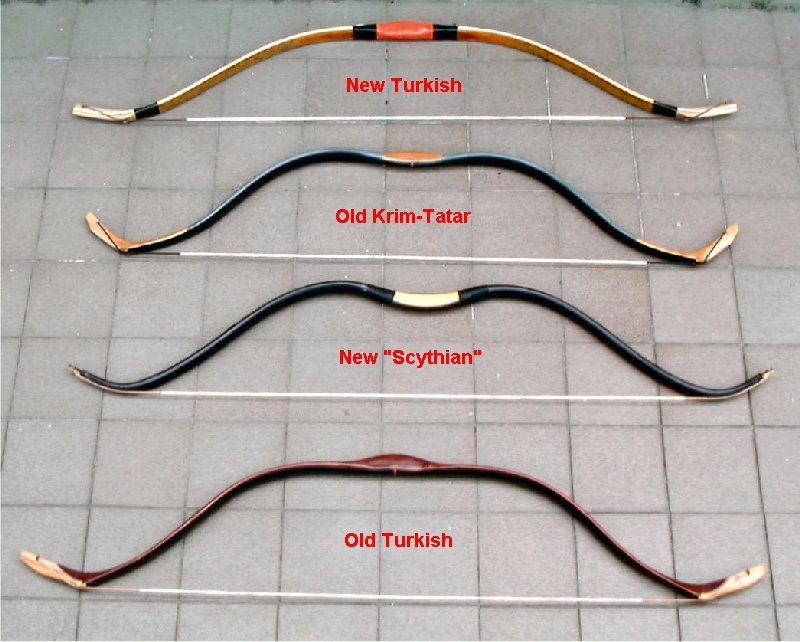

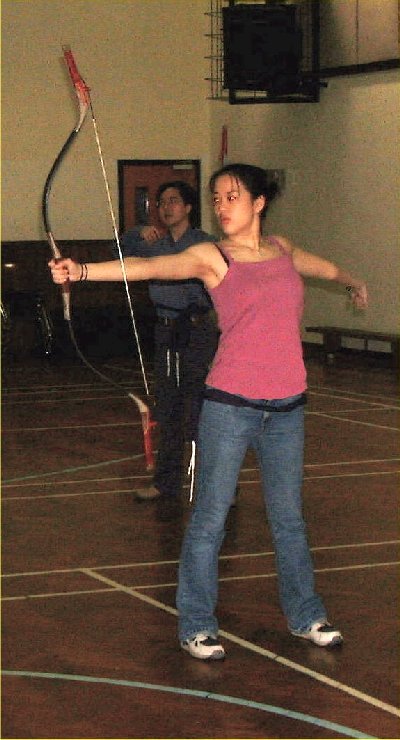

This letter announces a new article on Two Turkish Bows by Adam Karpowicz. The article describes two working reproductions of Turkish infantry bows that Adam made.

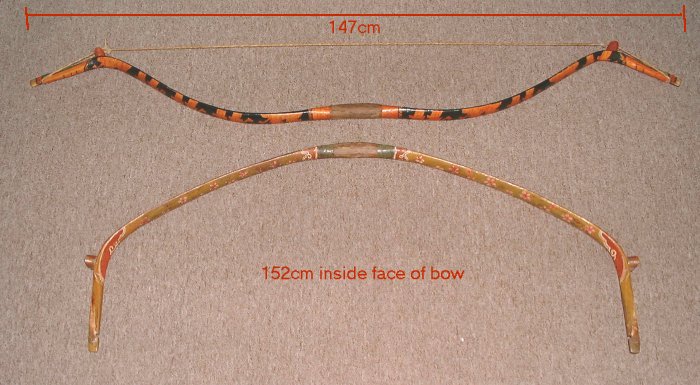

I thought I would add some photographs of an old Turkish bow made in about 1837. The length of the bow (measured along the limb from string nock to string nock) is 106cm.

The whole bow. 106cm string-nock to string-nock

Side view of grip

Decoration on back of bow limb

Detail of limb decoration

Bow tip with bone insert at the string nock and gilt decoration

'Chelik' or bone insert at grip between horn sections. (Note deliberate

roughening of the horn)

Horn belly of the bow limb. (Note deliberate roughening of the horn)

Signature of the bowyer, 'Ali Kawwsi'

Date (1837 in the Western Calendar.)

At first I was puzzled that a bow with such an artistic finish would have such crude roughening of the horn belly of the limbs. But perhaps the roughening is there for a specific purpose: to reduce glare from bright sunlight, which could impair the archer's aim. I checked using a Korean horn bow and found that at some angles, with the sun behind the archer, there can be an annoying glare.

Alternatively, is there any stricture in Islamic law against mirrors where the human face can be seen? Please would Muslim Members of ATARN let me know?

July 2001

Kay and Jaap Koppedreyer are back from Bhutan and Kay is promising us an article on Bhutanese archery and bow-making. I'm just putting this down on record so that she can't back out. As an encouragement, Kay, here's a nice picture of Himalayan archery - this is Dhanma, General to King Gesar of Hor, practicing a bit of horseback archery (Tibetan, around 1955.) I bought this painting in Edinburgh in the 1970s. It used to belong to the Tibet Scholar, Charles G. Bell.

September 2001

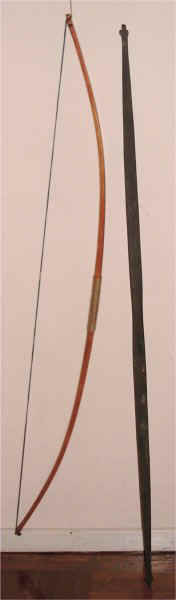

My holiday in North Wales was spiced up by meeting with a group of traditional archers at Llanbedrog, led by Nigel Burras. Nigel was my earliest archery teacher and he took an instant liking to my little Korean FRP bow supplied by Tom Duvernay. We ended up doing a swap: my Korean bow for a working reproduction of my Han Dynasty Chinese longbow. It shoots at about 50# drawn to 28".

Copy of a Han longbow by Nigel Burras of Llanbedrog

After coming back, I had some email correspondence with Jang Yuhua from Taiwan, who collects and shoots traditional Chinese bows.

Jang Yuhua of Taiwan with an old Chinese horn bow

We were swapping some experiences with bracing heavy Chinese bows and dealing with twists. Yuhua kindly agreed that we would share this correspondence with other ATARN Members. Here it is -

Yuhua:

Stephen, I'm afraid that I can not make it to FD this year. I have hurt my back big time by trying to string a very heavy bow(100#+) by the "Korean" method.I should get some "stringing device" for my heavy bows; but I don't know what kind of device the Chinese used. Right now the only thing I can do is to carry the heavier bows to the range and use a device there to string them and shoot them. The device is made from steel and is for use with modern recurve bows to measure the length of bow string. It's just not designed for the "C" shape of horn bows. Although I could easily pull a 100# Chinese bow, there was just no way to get it strung.

Best Regards

Jang,Yuhua

Stephen: Dear Yuhua,

I'm so sorry you can't come to FD: I had looked forward to meeting you.

You should not string a heavy bow like that. You must use two people, a bench

and 'gong nazi' for stringing. Look at this old photograph to get an idea of the

method.

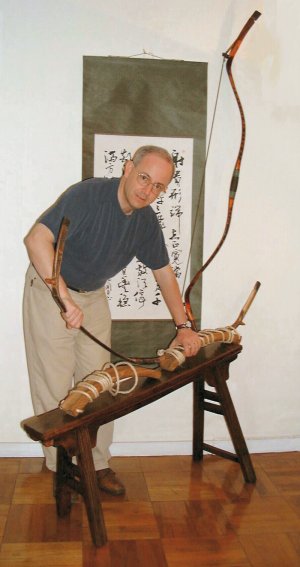

Here is a 'posed' picture of me using a bench and 'gong-nazi (tipliks) to prepare Chinese bows for stringing:

Remember that the very heavy bows ('hao gong') were not intended to shoot

arrows. They are only for drawing in the examinations.

Yuhua: From my experience a "C" shape horn bow with long

siyahs did draw much easier than a bow with short siyahs. It is so smooth you

can't feel much stacking. The force needed to draw it is pretty much the same

all the way through. It's a bit like a compound bow, yet much smoother than

that. For example, the "C" shape bow in the picture is about 120#, but

it draws like a 80# modern recurve and can deliver an arrow up to 300 meters.

Quite amazing!!

Stephen: I agree. The leverage from the siyahs allows stacking to be

avoided. The profile of the monkey bow is good. When a Chinese bow is in the C

shape, it is not ready to be shot. It has to be changed to an almost straight

profile using the 'gong nazi' before it can be strung and shot.

Yuhua: Stephen, you wrote: " When a Chinese bow is in the C shape,

it is not ready to be shot. It has to be changed to an almost straight profile

using the 'gong nazi' before it can be strung and shot. "

That doesn't make any sense to me. If a C shape bow has been heated, braced for a week and becomes like an almost straight profile, for sure it will loose a lot of power and won't able to perform a power "cast". The bow would just become "tired". I wonder if a bow has been treated like that, would it ever go back to its original C shape?

Stephen: In principle, your observation is correct.

But Chinese bows (in contrast to Korean horn bows) were designed for optimal

performance from a near-straight start when un-strung. A bow that has stood

unstrung for a long time is alright to string if the siyahs have an 'open' angle

(that is, they don't point inward towards each-other.) The relaxation into a C

shape with the siyahs pointing inward is a defect that arises over time from

excessive drying and shrinkage of the sinew. Over the winter, Mongolian nomads

leave their bows unstrung in a hut with frozen meat so that they will not become

too dried out. Shooting a Chinese or Mongolian bow from a C condition means that

the bow is performing at a heavier weight that the siyahs were designed to

stand, and risks over-stressing the sinew as well. (This information came from

Ju Yuan Hao.)

Of course, the bow should not be permanently strung.

In warm, humid conditions, the bow must be unstrung overnight and put in a

drying cupboard (pei gong xiang). In hot sunlight, even one hour may be enough

for the bow to soften below optimum performance. (Last year at Fort Dodge, in

very hot conditions, Munkhtesteg and Enkhbaatar unstrung their bows after every

round.) In the north, with cooler, drier weather, a light bow can be left strung

for a week, a heavy bow may be left strung for a whole season (if it does not

twist), and a strength bow used by a qigong master might not be unstrung for a

very long time, because it is such a nuisance to re-string it (as you have

discovered!).

Your concern about bows becoming tired and taking a set (following the string) are more relevant for wooden self bows or bows made with modern artificial materials. Chinese horn bows are much more tolerant.

Of course, one thing you must NOT do is to apply

force to bend the bow in the wrong direction. Doing that will split the bow at

the grip. Most of the Chinese bows I see have been damaged in this way, or by

being heated too much.

Yuhua: Thank you for the information. I could save some of my bows from

snapping at the siyahs in the future.

The other problem that bothers me is the twist problem. The way I deal with

it is to heat a strung bow then adjust it by hand. Is that correct? Or is there

some other ways to adjust it? Because a bow usually tends to go back to its

original twist angle after several weeks of use, I have to go through the

process over again. Each bow seems to have its own temper.

Stephen: Twist is a pain. Most of these natural bows are not perfect when

they were made, and you just have to live with their 'bad habits'. Often, the

twist is permanent, caused by a fault in the materials or uneven drying of the

glues.

I think you should heat the bow and remove the twist when the bow is unstrung.

The Mongolians have a special way of dealing with twist. They insert a 1/4" wooden rod across the angle of the limb and the siyah inside the loop of the string and fix it with tape. When strung, the rod can push the limb back against the direction of the twist. Another method I have seen on a horn bow from Tibet is to insert a ¼" slip of wood about 2½" long inside the loop against the string nock, with the aim again of distorting the strung bow against the twist.

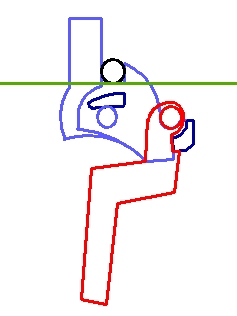

1/4" dowel inserted into a Mongolian bow to

correct a twist (side view)

1/4" dowel inserted into a Mongolian bow to correct a

twist (front view)

Sliver of wood attached to a Tibetan bow to correct twist.

Another piece is attached at the opposite side of the other bow-tip.

Note than with the Mongolian and Tibetan solutions, the bow can be shot while the remedial measure is in place. The Koreans use a completely different method for stringing and fixing twists in their horn bows. The methods described above are definitely unsuitable for Korean horn bows.

October 2001

I was at 40,000 feet over the Pacific Ocean on 11 September when four hijacked jetliners were used to attack the United States with such terrible effect. Our hearts go out to the bereaved families from 22 countries - and particularly those from the United States which suffered the worst losses.

Was it sheer coincidence that as these events unfolded I was reading of another terror attack, unprecedented at its time - the attacks of the Huns on Eastern Europe and Russia in 395AD? 'The World of the Huns' by Otto J. Maenchen-Helfen (Berkley, 1973) offers interesting material for those who like to read lessons from history. The Huns were poorly understood (and remain so.) No-one at the time could fathom their motivation: 'gratulabantur mortuis et vivos plangent.' (Glorying in the dead and lamenting the living.)

The Prophet, Muhammad, who possessed three bows, taught that skill in archery was a religious obligation (as reflected in sura viii. 62.) Some Islamic authors relate how the Archangel Gabriel had taught Adam that the bow is the power of God, the string is the might of God and the arrow the punishment of God. Chinese writers of the same period expressed the view that no man, while of sound body and mind, should ever give up the practice of archery. Laws to similar effect came into force at the time of English King Henry VIII. Countless other civilizations must have expressed the same idea in some way or other.

The tradition of archery has the potential to bring together people from all over the world. The most extreme exponents of Islam to the most moderate can choose to respect it, as, for that matter, can the people of North Korea or the USA.

More strident weapons of war will soon be heard before terrorism is eradicated. ATARN is dedicated to refining the bow and arrow as the weapon of peace.

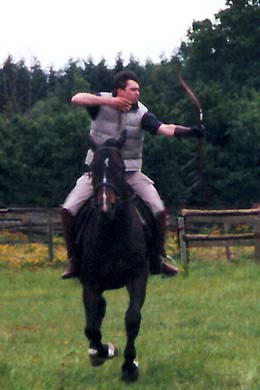

The International Horse Archery Festival 2001 at Fort Dodge had the great good fortune to finish two days before 11 September. It has gained in stature and experience from the first festival last year, and careful planning with indoor facilities allowed the event to be totally successful despite poor weather at times.

This year visitors could witness the whole process of Kassai's training programme for horseback archery. The biggest surprise for many must have been that an important element of the training takes place without any horses. Kassai has developed a set of military-style archery exercises, which help the student overcome the first hurdle - the transition from a gentlemanly sport to a martial art. Such a transition is vital to developing the hand-eye co-ordination and manual dexterity needed to handle a bow and arrow on horseback.

This year saw more intensive coverage of Kyudo, with workshops, rapid shooting displays and lectures. We also gained a rare insight into the cultural significance of archery in Africa, through a lecture from Cecelia Imunu from Southern Sudan. Practitioners from the native American nations were also present to share their traditional knowledge.

I was surprised how many people were prepared to get up early and practice Qigong exercises. My early morning class also looked at the relationship between Qigong and archery, and tried out some of the basic techniques of Chinese archery.

Next year, the Third International Horseback Festival will be back at Fort Dodge. There may be some 'taster' displays of different foot archery traditions, and the organizers hope to attract some archery cultures who have not been represented at Fort Dodge before. And -as always - there will be the drama and excitement of archery on horseback!

Many of you will be excited to learn that over the weekend after Fort Dodge, I was in Peking making a film (together with the Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence) on China's last traditional bow-maker, Ju Yuan Hao. We had a spectacularly successful day's filming which has resulted in an hour of professional video footage, narrated by the bowyer and his son, which will be sub-titled in Chinese characters and English.

Do not expect step-by-step instructions here. We are making two films: one of just fifteen minutes for continuous showing at the new Chinese archery exhibit at the Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence, which will be opened in the Spring of 2002; and the other for distribution to archery enthusiasts. Both of them will look generally at the techniques and the cultural background to the bowyer's craft in China. We have covered history, social organization, raw materials, cutting with the adze, gluing of the horn, laying-down of sinew, covering with birch-bark and decorative conventions.

Ju Yuan Hao has a genius for organization and for telling his story. While you would learn more technical detail from Tom Duvernay's film of the Korean master-bowyer of Kyongju or T'an Tan Chiung's 1930s study of bow-making in Chengdu, there are some surprising new insights to be gained from Ju Yuan Hao's experiences.