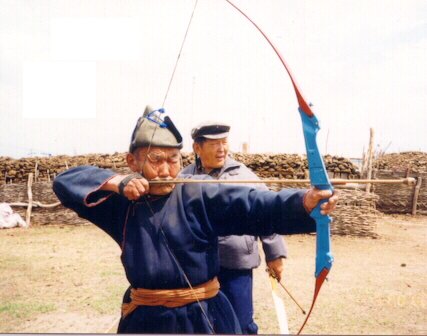

Buryat Traditional Archery near Hailar Banner, Inner Mongolia (Courtesy of © Jin Xiaofang)

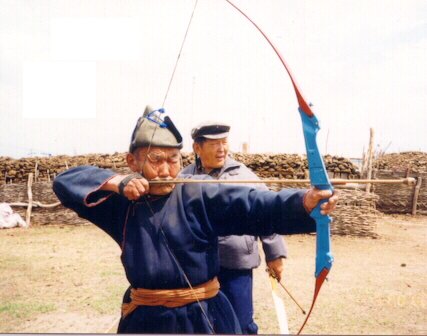

Bhutanese traditional archery (courtesy of ' © Tashi Delek', In-flight magazine of Druk Air)

Asian Traditional Archery Research Network (ATARN)

Text and photographs © Stephen Selby, 2001 except as otherwise indicated.

A1, Cloudridge,

30, Plunkett’s Road,

The Peak, Hong Kong.

Fax: (852) 2808-2887

email: srselby@atarn.org

March 2001

Dear All,

This month I am trying out the dangerous exercise of trying to shoot two birds with one pellet. The first 'bird' is to pass on some of my experiences of 'tradition' as it affects Asian archery. The other 'bird' is to introduce some Tibetan bows from Qinghai.

Buryat Traditional Archery near Hailar Banner, Inner Mongolia (Courtesy of © Jin Xiaofang) |

Bhutanese traditional archery (courtesy of ' © Tashi Delek', In-flight magazine of Druk Air) |

In the West, there is a lot of legitimate interest in the 're-creationist' aspect of traditional archery. But in the more distant parts of inner Asia where traditional archery remains a native tradition, I find few interested in faithfully recreating the past either in terms of equipment or in terms of technique.

Buryat Traditional 'cloth dragon' target (Courtesy of Jin Xiaofang)

A lot has to do with economics. Look at the three photographs above. There is no doubt in my mind that these activities are 'traditional', despite the fact that the archers have (a) obtained western bows and (b) adapted their style to the demands of western bows. Would these archers prefer 'traditional' bows? I don't know. Some will say that they would prefer traditional bamboo or horn and sinew bows, but they can't get them any more. Why can't they get them? Because no-one is making them. Why isn't anyone making them? Because the market for them is too small.

This slightly circular argument may obscure another point: many Asian traditional archers may grudgingly admit (although not to me) that western bows made with modern materials can be more accurate and consistent. Although many traditional archery practices are not primarily concerned with hitting the target, archers who miss do lose face in public. From attending some of these traditional events, it is clear that regularly but elegantly missing the target is not on the agenda. Once one archer has adopted western bows, what are the others to do?

An additional element is the investment of time and resources in maintaining bows and arrows made of traditional materials. Extremes of temperature and humidity affect such equipment greatly. In days gone by, when the bow was constantly at the nomads' sides, it was easier to keep them under constant minor maintenance. Now that they are not called upon other than for traditional sporting events, and are laid-up for long periods of time, looking after them has become more difficult.

There are exceptions, of course. In outer Mongolia, where archery is one of the 'three manly sports' at the national-level Nadam competition, traditional equipment, targets, costumes and songs are all de rigueur. The traditional technique, however, is largely optional. The bows discussed below also reveal a dedication to traditional equipment in Northern Tibet.

Why do Central Asian people persist with any traditional element in their archery, then? The answer does not seem to lie either in any nationalistic feeling of superiority about their equipment or their techniques. Rather, it seems to be to do with asserting a part of their national characteristic represented by archery. When I look further-afield to Korea and Japan, a different picture emerges: these two great archery traditions incorporate a layer of influence from China in which competition is secondary and ritual detail is an important element of the overall procedure.

In recent months, ATARN Member Xu Kaicai (a Chinese national archery coach who travels very widely in China) has drawn my attention to some fine traditional bows from Haixi (Tib. Tsonub) Prefecture of Qinghai Province, West China. These bows are made and used by the Tibetan nationality.

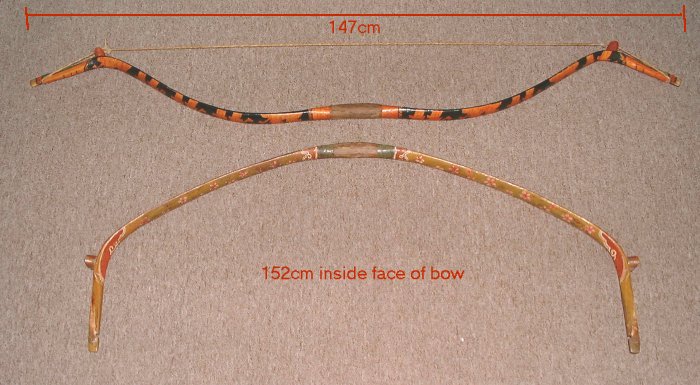

Two modern Tibetan horn/sinew bows from Haixi Prefecture, Qinghai Province,

China.

These two bows are close to Chinese and Manchu bows in their construction, although they are much smaller. The ethnic mix in Haixi Prefecture, Qinghai is complex, both because of a longtime population of Mongols and Tibetans in the region as well as due to forced emigration of Mongols from Inner Mongolia to Qinghai and Gansu at the time of Sino-Soviet tension in the late 1950s.

The bow is smaller than the 'women's size' bows now used in Khalkha regions of Outer Mongolia.

Limb detail and decoration

Siyah detail and decoration. Note the rawhide string.

The bow-tip and string nock reinforcement is in white sheep's horn. The string

bridge is made of wood.

Grip detail. The grip is covered with an unidentified vegetable bark or pith.

Decoration near the grip. All decoration is applied with a black lacquer

paint over natural birch bark.

Antique bows of a similar design. The upper bow is over 100 years old. The

lower one is around 60 years old.

Modern arrows accompanying the bows. Length (nock to base of point) 78cm.

Point: 2cm. The arrows are barreled: 7mmŲ at the base of the tip, 10mmŲ in

the middle and 5mmŲ at the base of the bulb nock.

Details of the arrow decoration. Cresting in coloured silk with lacquer

covering. Shaft decoration in peach bark.

When I talk of these bows being 'made' I am being slightly misleading. The four specimens I have examined (both new and antique) are all made with horn recycled from older bows. I would hazard a guess that in all the cases, the horn came from Chinese bows made in Peking or West China because the dimensions of the horn are identical to those of Chinese mounted archery bows.

The top bow in the first photograph is clearly brand-new. The construction is very sound and the quality of the materials and decoration is superior to modern bows now being made in Mongolia. The draw-weight has not been measured, but it seems to be around 60 pounds (27kg) at 28 inches (71cm).

In terms of decoration, all the bows show strong Chinese influences. The lower bow on the first photograph is decorated with a medlar blossom design (hai tang) - the Chinese rebus for 'elevated rank'. Other decorative elements such as the use of ray skin on the arrow-pass and the key-pattern near the grip are also Chinese. The oldest of the bows has the Chinese character 'wang' ('king') impressed in the horn tip. This may indicate a Chinese bowyer; but 'wang' can also be a sinification for certain Tibetan names.

Are these the bows represented in this illustration from the 1930s? The way

the string is attached to the limb below the siyah cannot be accurate. (Public

domain photo)

The older bow also has repairs done with sinew tightly wound around weak points in the limbs, as well as a wooden build-out below the string-nock to correct a slight twist in the limb. I am told that the oldest bow was the property of a Lama and was shot up until recently in religious sports festivals.

The arrows are almost more impressive than the bows. They are made of wood (probably a common scrub wood known in Chinese as 'liu dao mu' ('six channel wood'.) They are skillfully barrelled and a lot of effort has gone into decoration and finishing. They each have a forged and filed iron tip and an bulb nock.

Two things to say in conclusion. First, there is a fine bowyer out there in Haixi prefecture. I hope to be able to meet him sometime. Second, these bows (and indeed many bows that I have collected) demonstrate the importance of re-cycling of materials in traditional bow construction. I have one Qing bow, which incorporates wood in the siyah bearing a date of the Yongle period of the Ming Dynasty (1403-1424). As there is nothing to make me suspect that the inscription is a fake and the bow is clearly of Qing design, it is likely that the inscription is on a re-cycled part. In many other bows, the horn is of greater antiquity than the wood or the decoration.

I have to inform you with regret that the Symposium originally planned for May 2001 has got to be deferred again until next year (2002), due to the difficulty in finding dates to suit all the co-organizers.

|

(Signed) (Stephen Selby) |

Haixi Mongolian and Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture comprises about 45% of the territory of Qinghai province, but only 7% of its population. Of this population, 76% are Chinese, 10% Tibetan, 7% Mongol, and 5% Hui (Muslim Chinese).