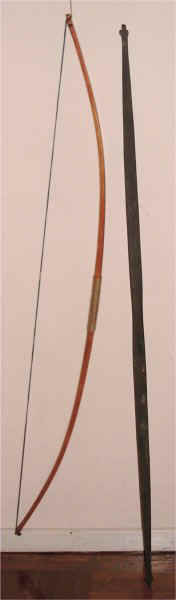

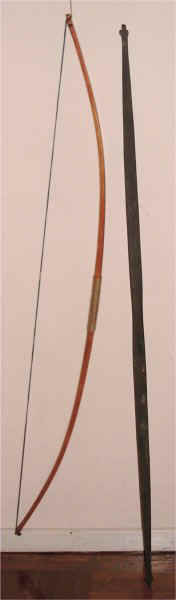

Copy of a Han longbow by Nigel Burras of Llanbedrog

Asian Traditional Archery Research Network (ATARN)

Text and photographs © Stephen Selby, Jang Yuhua, 2001.

A1, Cloudridge,

30, Plunkett’s Road,

The Peak, Hong Kong.

Fax: (852) 2808-2887

email: srselby@atarn.org

September 2001

Dear All,

You get your September letter a little early, because I'm off to Fort Dodge for the 2001 International Horse Archery Festival. Check out their web page by clicking on the link. Come if you can!

For those of you who have XML-enabled web browser software, you can read three classic books on Chinese horseback archery, and brush up your skills for Fort Dodge.

My holiday in North Wales was spiced up by meeting with a group of traditional archers at Llanbedrog, led by Nigel Burras. Nigel was my earliest archery teacher and he took an instant liking to my little Korean FRP bow supplied by Tom Duvernay. We ended up doing a swap: my Korean bow for a working reproduction of my Han Dynasty Chinese longbow. It shoots at about 50# drawn to 28".

Copy of a Han longbow by Nigel Burras of Llanbedrog

After coming back, I had some email correspondence with Jang Yuhua from Taiwan, who collects and shoots traditional Chinese bows.

Jang Yuhua of Taiwan with an old Chinese horn bow

We were swapping some experiences with bracing heavy Chinese bows and dealing with twists. Yuhua kindly agreed that we would share this correspondence with other ATARN Members. Here it is -

Yuhua:

Stephen, I'm afraid that I can not make it to FD this year. I have hurt my back big time by trying to string a very heavy bow(100#+) by the "Korean" method.I should get some "stringing device" for my heavy bows; but I don't know what kind of device the Chinese used. Right now the only thing I can do is to carry the heavier bows to the range and use a device there to string them and shoot them. The device is made from steel and is for use with modern recurve bows to measure the length of bow string. It's just not designed for the "C" shape of horn bows. Although I could easily pull a 100# Chinese bow, there was just no way to get it strung.

Best Regards

Jang,Yuhua

Stephen: Dear Yuhua,

I'm so sorry you can't come to FD: I had looked forward to meeting you.

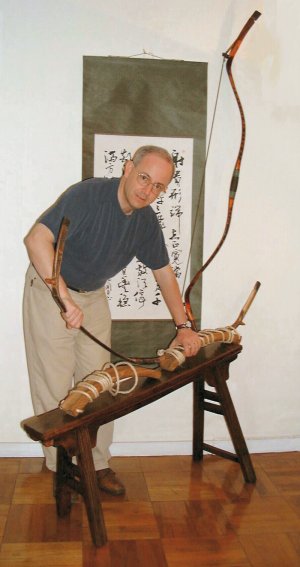

You should not string a heavy bow like that. You must use two people, a bench

and 'gong nazi' for stringing. Look at this old photograph to get an idea of the

method.

Here is a 'posed' picture of me using a bench and 'gong-nazi (tipliks) to prepare Chinese bows for stringing:

Remember that the very heavy bows ('hao gong') were not intended to shoot

arrows. They are only for drawing in the examinations.

Yuhua: From my experience a "C" shape horn bow with long

siyahs did draw much easier than a bow with short siyahs. It is so smooth you

can't feel much stacking. The force needed to draw it is pretty much the same

all the way through. It's a bit like a compound bow, yet much smoother than

that. For example, the "C" shape bow in the picture is about 120#, but

it draws like a 80# modern recurve and can deliver an arrow up to 300 meters.

Quite amazing!!

Stephen: I agree. The leverage from the siyahs allows stacking to be

avoided. The profile of the monkey bow is good. When a Chinese bow is in the C

shape, it is not ready to be shot. It has to be changed to an almost straight

profile using the 'gong nazi' before it can be strung and shot.

Yuhua: Stephen, you wrote: " When a Chinese bow is in the C shape,

it is not ready to be shot. It has to be changed to an almost straight profile

using the 'gong nazi' before it can be strung and shot. "

That doesn't make any sense to me. If a C shape bow has been heated, braced for a week and becomes like an almost straight profile, for sure it will loose a lot of power and won't able to perform a power "cast". The bow would just become "tired". I wonder if a bow has been treated like that, would it ever go back to its original C shape?

Stephen: In principle, your observation is correct.

But Chinese bows (in contrast to Korean horn bows) were designed for optimal

performance from a near-straight start when un-strung. A bow that has stood

unstrung for a long time is alright to string if the siyahs have an 'open' angle

(that is, they don't point inward towards each-other.) The relaxation into a C

shape with the siyahs pointing inward is a defect that arises over time from

excessive drying and shrinkage of the sinew. Over the winter, Mongolian nomads

leave their bows unstrung in a hut with frozen meat so that they will not become

too dried out. Shooting a Chinese or Mongolian bow from a C condition means that

the bow is performing at a heavier weight that the siyahs were designed to

stand, and risks over-stressing the sinew as well. (This information came from

Ju Yuan Hao.)

Of course, the bow should not be permanently strung.

In warm, humid conditions, the bow must be unstrung overnight and put in a

drying cupboard (pei gong xiang). In hot sunlight, even one hour may be enough

for the bow to soften below optimum performance. (Last year at Fort Dodge, in

very hot conditions, Munkhtesteg and Enkhbaatar unstrung their bows after every

round.) In the north, with cooler, drier weather, a light bow can be left strung

for a week, a heavy bow may be left strung for a whole season (if it does not

twist), and a strength bow used by a qigong master might not be unstrung for a

very long time, because it is such a nuisance to re-string it (as you have

discovered!).

Your concern about bows becoming tired and taking a set (following the string) are more relevant for wooden self bows or bows made with modern artificial materials. Chinese horn bows are much more tolerant.

Of course, one thing you must NOT do is to apply

force to bend the bow in the wrong direction. Doing that will split the bow at

the grip. Most of the Chinese bows I see have been damaged in this way, or by

being heated too much.

Yuhua: Thank you for the information. I could save some of my bows from

snapping at the siyahs in the future.

The other problem that bothers me is the twist problem. The way I deal with

it is to heat a strung bow then adjust it by hand. Is that correct? Or is there

some other ways to adjust it? Because a bow usually tends to go back to its

original twist angle after several weeks of use, I have to go through the

process over again. Each bow seems to have its own temper.

Stephen: Twist is a pain. Most of these natural bows are not perfect when

they were made, and you just have to live with their 'bad habits'. Often, the

twist is permanent, caused by a fault in the materials or uneven drying of the

glues.

I think you should heat the bow and remove the twist when the bow is unstrung.

The Mongolians have a special way of dealing with twist. They insert a 1/4" wooden rod across the angle of the limb and the siyah inside the loop of the string and fix it with tape. When strung, the rod can push the limb back against the direction of the twist. Another method I have seen on a horn bow from Tibet is to insert a ¼" slip of wood about 2½" long inside the loop against the string nock, with the aim again of distorting the strung bow against the twist.

1/4" dowel inserted into a Mongolian bow to

correct a twist (side view)

1/4" dowel inserted into a Mongolian bow to correct a

twist (front view)

Sliver of wood attached to a Tibetan bow to correct twist.

Another piece is attached at the opposite side of the other bow-tip.

Note than with the Mongolian and Tibetan solutions, the bow can be shot while the remedial measure is in place. The Koreans use a completely different method for stringing and fixing twists in their horn bows. The methods described above are definitely unsuitable for Korean horn bows.

|

(Signed) (Stephen Selby) |