Asian Traditional Archery Research Network (ATARN)

Text and

photographs © Stephen Selby, Trinidad Campbell, 2002.

A1, Cloudridge,

30, Plunkett’s Road,

The Peak, Hong Kong.

Fax: (852) 2808-2887

email: srselby@atarn.org

October 2002

Dear All,

Noted with appreciation the occasional withdrawal symptoms expressed by Members who couldn't find the August and September newsletters. I never wrote them. I have been away on travels: Wales, Hungary and Fort Dodge.

Hong Kong's local broadcaster, Radio Television Hong Kong, has made a documentary with my help about Chinese archery. It was shown in Chinese on 10 August and if you want to see it, they have made it available in streaming video. You can watch it by clicking here. I shall let you know when it comes out in English.

At the age of six, Csaba Grózer (pronounced like 'Chaba Grocer') had a vision that he would make a bow - something that he had hardly ever seen as a young boy growing up under Communist rule in Northwest Hungary. At first he made simple bows from materials that he could lay his hands on. As time went on, he tried his hand at more sophisticated bows. He avidly read up on archaeological discoveries from Avar kurgan graves, such as those of Professor Gyula László, Cs. Sebestyen Karoly and Fabian Gyula.

Csaba Grózer

In the early part of the 20th Century these researchers had thoroughly discussed the history of Magyar and Avar archery, and László and his son successfully reproduced an number of ancient bows using traditional materials. László was conscripted during the Second World War and ended up a prisoner-of-war in the Far East, where he was able to observe Asian bow-making first-hand. Both he and his son travelled and learned many secrets of the bowyers' craft, but tragically both were killed on war duty and their secrets went with them to the grave.

Despite this loss, their work confirmed for the Hungarian people their long tradition as renowned archers. Under the Soviet yoke, these cultural fragments were treasured among patriotic Hungarians and laid the ground for an explosion of interest in post-Soviet times.

Csaba Grózer became more and more deeply involved in bow-making. His parents despaired. How was their son ever going to make a living out of making bows? Where was the market? How could he compete with products from the West? Csaba decided to go to technical college after graduating from high school. Armed with a proper, academic understanding of material mechanics, he settled down to making bows and exploring modern materials throroughly together with more traditional materials.

Starting modestly, he developed his own shooting skills with the traditional Hungarian bow and took a small stock of products to regional sporting events. In those days, international archery was new to Hungary. Despite the fact that other competitors were using modern bows with sights and counterbalances, Csba was able to out-shoot them using a reproduction of an ancient Avar bow (something he admits he would not be able to get away with nowadays!) His bows were not expensive. Some spectators and enthusiasts would buy a couple, mainly to hang on their walls as an emblem of Hungarian national pride.

Gradually, a distinct interest grew up among Hungarians in their traditional bows. They were inexpensive (being a local product) and fun to shoot. Csaba's market grew.

Csaba was not the only one making bows in Hungary. Other bowyers such as Kassai Lajos were also making fine bows. Kassai's revival of the ancient Hungarian tradition of horseback archery was creating a lot of excitement. Interest in Asian bows also grew in Europe and the USA as re-enactment groups became more popular.

Nowadays, Csaba Grózer has diversified his output to cover a very wide selection of Asian and Middle Eastern bows. His home and factory are at Feketeerdö, near the border with Austria. He is in two minds about this broad range of stock. Some of his bows (Assyirian and Scythian) he admits are little more than 'fantasy bows' with little or no archaeological or scientific background. Others among his repertoire are faithful reproductions of historic bows (for example his Hungarian range of bows and his Turkish and Crimean Tartar bows.) He wishes that he could cut down his repertoire and concentrate on faithful historical reproductions. But his wide range is a boon as well as being a burden: they feed a ready market. Csaba reckons that in recent years, his output has exceeded that of some of the big US makers.

Despite his dedication to historic replicas, Csaba's 'Holy Grail' is to discover the 'perfect bow' through a study of historical bows worldwide. Although we mainly know him through his work with fiberglass bows, he has a steady output of traditional horn and sinew bows.

Csaba keeps a few Hungarian

grey long-horn cattle, whose horns

he sometimes uses in his bows.

I asked Csaba what he felt was the key to sustainable development of traditional archery in areas like China. (He and I are co-operating on a project to raise the profile of traditional archery in China.)

"First, the bows must be sufficiently cheap. It's no good if traditional archery is just an amusement for the wealthy. Second, you need a properly thought-out programme, where the first step is to train trainers. There must be sufficient affordable bows and arrows, as well as enough opportunity to learn traditional methods to meet the demand."

Csaba chided me gently for having popularized a style of Asian and Chinese archery with a long draw. He finds himself constantly having to argue with clients who demand traditional bows with a 'traditional' long draw of over 30". "Only Mongolian, Korean, Chinese and Japanese bows are drawn like that. For the traditional Avar, Turkish, Crimean and Hun models, no more than 28" to 30" is required. More than that puts more stress on the bow than it was ever designed to take," he says.

Find more about Csaba Grózer's bows from his web-site.

This year, I jumped the fence at Fort Dodge International Horse Archery Festival, becoming a student rather than an instructor (of qigong and Chinese archery.) As an observer 'from the outside' in previous years, I had already been privileged. Kassai Lajos had been trying to draw me into horseback archery, generously allowing me to join his groups for ground training. Lucas Novotny had made valiant efforts to get to grips with my poor and un-confident horsemanship.

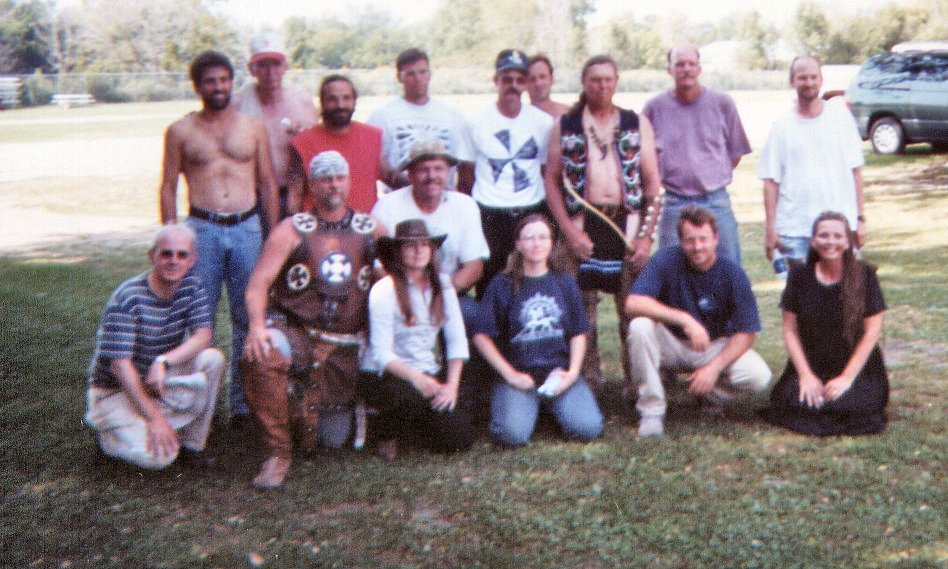

So joining as a novice was no shock for me; but perhaps it could have been for other neophytes. Nevertheless, everyone took to it with a will: I (as a former outsider), Kassai and Lucas agreed that this year's group at Fort Dodge was the most committed and cohesive to-date.

A tight-knit group (we missed John-Paul, who was hurt in a fall but has now

recovered.)

To understand what goes on at this training, you have to understand some of Kassai's previous experiences. He has a background in the army, and early on he realized that the dangerous sport of horseback archery required dedication and discipline to master. Military discipline.

In his own horseback archery training camp in Hungary, he has to cope with self-proclaimed archers and riders who are there to 'have fun'. Horseback archery, says Kassai, is not something that can be done just 'for fun'. He finds that, like over-excited horses thrown together for the first time, he has to cool down temperaments and get co-ordination and co-operation going before any training can start. In Hungary, he does that by getting people away from horses and bows and getting them started with some simple, menial tasks around the camp. Some have resented this as a sign of an overbearing character. Kassai counters that such a stage is vital to cool the tempers of riders and create an atmosphere of co-operation and mutual support.

In Fort Dodge, things happen differently from Hungary. Time is limited and obtaining useable horses is not easy, despite the generosity of the local horse-breeding community.

Kassai supervising ground-work. Balance and nocking from an

unfamiliar position.

Photo credit:

Trinidad Campbell

The Fort Dodge training starts off with military parade-ground drills, followed by archery drills with a military flavour. These serve to wean archers off conscious aiming into an instinctive form of shooting, to give archers a realistic understanding of their own limitations and to speed up reactions. Maybe it's a clue to the essence of this training that in three years, I have never heard Kassai chide a student for failing to hit the target.

Later in the morning we get some work on horseback. The main purpose at the early stage is to improve students' balance and ability to exploit the rhythm of the horse. We also practiced some of the morning's parade-ground drills on horseback.

At the first day's horseback training, trainers have to assess the riders' ability to ride their mounts. The more able riders are allowed to start training at the archery course, while the rest have to continue basic training such as spear-throwing from horseback.

The main afternoon activity of each day is held at the horseback archery track. Beginners have to act as assistants, pulling arrows and helping to keep score for competitors. Through this work, beginners, while not able to partake in the full-scale horseback archery training, get to understand the rules of the competition and the co-operation and mutual support that is vital for developing skills and minimizing risks.

Lucas Novotny knows where his arrow is going. His horse is not so sure...

Photo credit:

Trinidad Campbell

For some reason, the horseback archery training this year was very limited for beginners. An important element at the early stage in previous years has been individually-guided work bareback on a lunging rein. For some reason, that was dropped from this year's programme.

At the very end of each day is an event that everyone is required to participate in: after horses are cooled, watered, fed and stables cleaned, every student, whatever his or her level, sits with Kassai in a circle. Each takes turn to speak about his internal feeling about the day and about the general organization of the event. Given the thrills and spills of the training programme, these could be tense and emotional events. Apart from providing feed-back from students, it serves the same purpose as cooling off the horses: everyone winds down at the end of the day.

What are the demands of the Fort Dodge training programme on participants? Confidence (but not over-confidence) on horseback, stamina and dedication. Ounce for ounce, what you get out of the course depends on what you put in. Do not imagine that what you pay to take part in the course gives you a through-ticket to the end result.

A fine shot from Todd Delle.

Photo credit:

Trinidad Campbell

I would also say that you need a great deal of patience. Kassai's English is imperfect and communication can sometimes be painful. The work is hard. The horses are unlikely to be well-matched to the rider (I was lucky to be assigned a Rolls-Royce of a horse that could learn more quickly than I could!) Finally (at the risk of being chastised by the organizers) you must appreciate that this is a very dangerous sport. Once up on a horse, you are the captain of your ship and you must be prepared to say loudly and firmly if you are faced with a demand that you regard as beyond your riding abilities. You may be chivvied into giving something a try, but you must have the determination not to be peer-pressured into something that will end you up in hospital. Perhaps it was on account of my old gray hair that Kassai readily excused me if I admitted that the going had got too hard for me.

This year, I think, was a pivotal year for the Fort Dodge horseback archery training. I expect next year's event to be marked by positive new developments in organization and safety procedures. The past three years have laid the ground for more effective, safe and sustainable training programmes in the future. Join up!

|

|

(Signed) (Stephen Selby) |