Asian Traditional Archery Research Network (ATARN)

A1, Cloudridge,

30, Plunkett’s Road,

The Peak, Hong Kong.

Fax: (852) 2808-2887

email: srselby@atarn.org

Spring 2003

Dear All,

If you had dreams that I would make a new year's resolution to get ATARN newsletters out on time, well... dream on! Actually, I did resolve to make better excuses for getting them out late, but I've already broken that.

You will have gathered if you follow ATARNet that I am in the throes of preparing a museum catalogue for our archery museum exhibit that is set to open on 15 May 2003. Members have been really fantastic in providing positive comments. As you can all see, I have no experience in making bows and so everything I write on the subject of bow-making and its materials attracts a lot of good-humored flack. Keep the comments and the smilies coming, and this will be a really good production.

The Rotary Club of Hong Kong North has made a handsome donation to ATARN to help promote traditional archery in China. We have already received 30 traditional Chinese bows in modern materials as well as modern targets and arrows. I am starting close to home here in Hong Kong with ten, two-hour classes in Chinese traditional archery held at the Vocational Training Institute in Morrison Hill, Wanchai on Sunday mornings from 09:30 to 11:00.

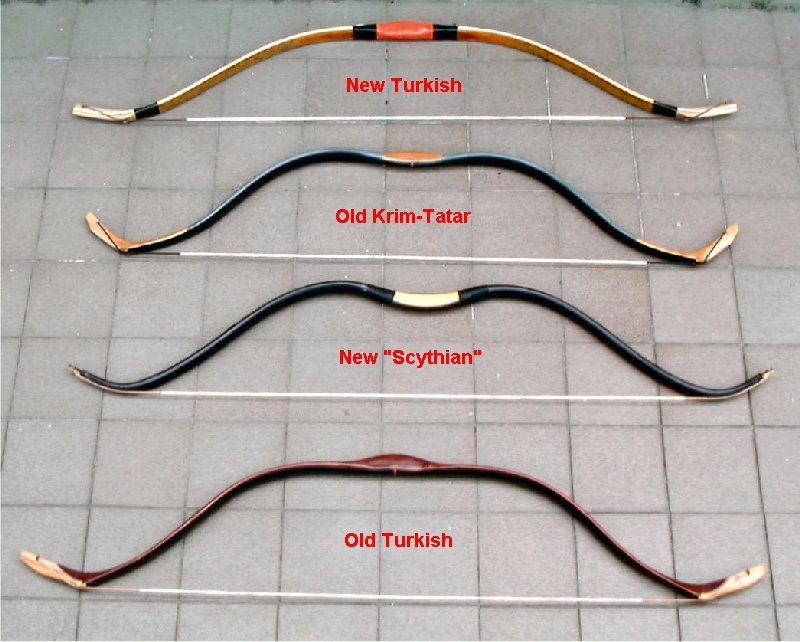

Csaba Grozer has been experimenting with new TRH laminated, composite bow-making techniques.

You can see two of these bows compared with bows from his existing stock. They are pictured against 15cm (6") squares.

Grabbing half a dozen different bows with varying draw-weights and draw lengths and comparing them on a chronometer is not as easy as you would think. I had to shoot from three meters distance with a 30" draw over the sensors of the chronometer and into a backstop net in order to get any sensible readings. Here is a tabulation of the results:

| Bow | Average recorded speed in feet per second |

| A 66" Chinese bow by Lucas Novotny of Saluki (50#) | 172.5 |

| Csaba Grozer's original Chinese bow design (45#) | 158.5 |

| Csaba Grozer's new Chinese bow design (45#) | 161.8 |

| Csaba Grozer's new Scythian bow design (45#) | 160.2 |

| Csaba Grozer's original Crimean Tatar bow design (45#) | 151.7 |

| Csaba Grozer's original Turkish bow design (50#) | 167.3 |

| Csaba Grozer's new Turkish bow design (50#) | 174.3 |

I have also taken the bows together with a set of six, matched wooden arrows and shot at my target using the same 30" draw, trying to get a feel for the differences.

You should note that Csaba has not attempted to add any decorative finish to some of he new bows. This made the two Turkish-style bows difficult to compare, because the lack of leather covering on the limbs of the new bow is bound to have an effect on the bow's speed right from the start.

And indeed it did. The new design felt very quick. It was also not so heavy to draw (stacked less), but there was another issue at play here: unlike Csaba's older Turkish bow, the new bow does not have a marked reflex when unstrung. I still regard the older Turkish design as superior, and the best value-for-money bow of this design on the market.

Csaba's 'Scythian' bow design is, by his own reckoning, a 'fantasy' design: it only bears a passing resemblance to known images of historical Scythian bows. But this little new bow is a real performer. It was fast and smooth to draw.

Grouping with the new Scythian at 15 metres. (thumb ring

draw).

I felt real power in the bow and a smooth draw. The grip is well built out so that there is no discomfort at full draw (a problem with the beautiful Krim-Tatar design, which has a very slim grip.) I think that the new Scythian design could have a great market as a generic horse bow (with no pretension of historical precedent.) Perhaps Csaba could go for a 'no-nonsense' black fibergalss limb with no leather cover (even more speed!)

Kudos to Csaba Grozer for pushing the envelope of traditional bow design with modern materials!

In 1954-55, Malayan resident N. W. Simmons traveled widely in Asia and kept a record of all he could find about local archery traditions. He published his findings in The Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society [Vol. XXXII, Pt. 1, 1959] His article is an excellent snap-shot of traditional archery as he found it then, and I am taking the liberty of summarizing some of his report below.

Polynesia

Pitt Rivers had communicated about the use of bows for sport and ritual among chiefs on the Society Islands in 1914. Simmons speculated that the bows are used for displays of strength.

Fiji and Tonga

The use of bows and arrows in hunting was reported to have stopped with the Cession in 1876. Bows were made from mangrove wood (Rhizophora and Haplopetalon.) A groove in the wood of Fijian bows caused by the structure of the mangrove root has been misinterpreted by some writes as something made be the bowyer to allow an arrow to be gripped against the limb of the bow. The bows were 130-180cm in length with elegant nocks. The strings were made from the fibres of a variety of hibiscus and waxed. Arrows were made from a bamboo-like grass. Heads of the arrows were made of hardwood, bone, or reverse conical hardwood knobs for hunting birds in trees. Arrows were un-fletched with shallow nocks as are often found among people who use a short pinch draw.

New Hebrides

New Hebrides bows were similar in construction to Fijian and Tongan bows, but were a little linger (150-200cm) and string shorter, so that there there was a length of bow-tip visible at each end (although Simmons suspected incorret stringing by museum curators.) No nocks were visible. Apart from Mangrove, some bows were made of hardwood or palm, and plano-convex to oval in cross-section.

In the northern New Hebrides, bows were differentiated into fighting and ceremonial bows. Fighting bows were more robust, and ceremonial bows were asymmetrical (less bent in the lower limb) and somewhat recurved in shape like an Andeman bow. Arrows were made of long, bamboo-like grasses with shallow nocks (with a few exceptional deep nocks), both crudely fletched and unfletched.

Solomon Islands

Bows from Rennel and Bellona Islands were one metre or less, with elaborate carved nocks. Arrows were made from straightened twigs. Another bow design had an elaborate cap to permanently attach one of the string ends to the bow tip, formed to hold the string a short distance from the face of the bow and made of fibre hardened with breadfruit latex gum. The free end of the string had a whipped knot. In the South-east Solomons, some bows made from palm wood had their limbs decorated with red and yellow dyed rattan. The skin side of the palm wood was on the belly. Arrows were made from grass and had shallow nocks or no nocks at all. They were unfletched and the points were made of palm splinters. The bows were draw with a pinch hold, the index finger slanted across the string and the bow canted to the right.

New Guinea and Papua

The majority of bows are made from palm (Archontophoenix) called 'limbom' in Pidgin and are 150-220cm long, plano-convex or oval in cross-section, and have the skin of the palm at the belly. The nocks are conical at the tip of the limbs. In some areas, rings of plaited calamus were applied as nocks. Some isolated mountain communities (e.g. in the Goroka area) use smaller bamboo bows.

Another type of bow used in the Fly and Trans-Fly country was made from thick-walled bamboo staves bent skin to belly and were over two metres long.

Strings were made from four types of materials: calamus, bamboo skin, bamboo attached with cords or just cords.

A wide range of materials and designs were used for arrow points. Some were elaborate and presumably had a magical significance. The arrows were made of bamboo and were unfletched. Poisons used on all Papuan points were made from putrefying flesh. The Papuans did not use plant poisons, although they were aware of the very poisonous nature of some of their local plants (e.g. the Upas tree.)

Shooting was done with the pinch hold, assisted with the middle and ring fingers. The shafts of the arrows were very long and not matched, so that no attempt was made to fix the draw to any particular point, although some tribes with a warlike reputation did attempt to match their arrows and achieve a consistent draw length. The bows were canted to the right and sometimes held horizontally. The Fly and Trans-Fly people raised the bow above their heads and then brought the bow arm down to the draw. They also used bracers to protect the bow forearm. The accuracy of shooting observed among the Papuans was very low: they relied mainly on excellent stalking skills.

Over the past three years, I have tried to develop an Asian archery festival in Hong Kong. It is a truly roller-coaster experience. I have come so close, and yet it seems that even our fully advanced and generously-sponsored 2003 Asian Archery festival is under last-minute threat from the pneumonia outbreak that has dogged Hong Kong and other cities in recent months. Please keep your fingers crossed that the event can go ahead in May. However, if by mid-April we lack the confidence to continue with the event, we shall postpone it to an alternative date later in the year.

Gustave Doré "Cupid"

|

|

(Signed) (Stephen Selby) |